This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 26 no. 3, pp. 14-25

Contemporary dance education. Gaps and goals

Natalie Gordon, Caroline D'Haese

Koninklijk Conservatorium Antwerpen

Dance education faces many challenges today. Both our society and the field of contemporary dance have changed to such an extent that dance educators are required to critically rethink traditional teaching methodologies. Based on their two-year research project ‘The Role of Vocabulary in Contemporary Dance’, Natalie Gordon and Caroline D’Haese identify in this article some of the most pressing gaps and goals in contemporary dance education. Their practice-based expertise leads them to formulate a constructive proposal for reconfiguring dance education today.

Dansonderwijs staat vandaag de dag voor vele uitdagingen. Zowel onze samenleving als het veld van de hedendaagse dans zijn de voorbije jaren zodanig veranderd dat dansdocenten zich genoodzaakt zien om traditionele onderwijsmethoden kritisch onder de loep te nemen. Op basis van hun tweejarig onderzoeksproject ‘The Role of Vocabulary in Contemporary Dance’ identificeren Natalie Gordon en Caroline D’Haese in dit artikel enkele van de meest prangende hiaten en ambities in de huidige danseducatie. Vanuit hun praktijkgerichte expertise formuleren ze een constructief voorstel voor het hedendaagse dansonderwijs.

Contemporary Dance Artists: Sketching the Profile

© Boris Bruegel

What does it mean to become a contemporary dance artist today?1 The current expectation is that dance artists communicate eloquently about artistic research; have the social skills to work in a group under high pressure and deadlines; can research and document creative processes; can teach in diverse contexts to a range of target groups; are able to learn challenging movement sequences at speed or contribute choreographic material in the movement language or style of a specific production. In essence, like many contemporary artists working in other fields, dance artists must excel on multiple levels of their artistic practice, including: performing, mentoring, choreographing, evaluating, fundraising and writing. And if any of the above skills are not present in their own range of talents, they can network to find the right collaborators. On top of this, the precarious socio-economical position of being a freelance dance artist entails yet another set of demands, such as financial and job security, insurance, long-term health and injury prevention, professional development, place of residence, working visas, and parenting.2

Professional dance education faces the challenge to identify, analyse and contribute actively to the main tendencies of the current dance field to support students towards this evolving and complex environment. Additionally, education must respond to a changing society3 ; we are not teaching the same dance students as twenty years ago. Attitudes, needs, expectations, communication, and personal ambitions have all evolved profoundly. The conditions have even changed to such an extent that there may well be a more direct link between the arts and society. Ultimately, the variety of skills a creative (dance) artist acquires are often skills pioneered in the arts first, before they get picked up as quintessential skills in business models today. According to Stefan Hertmans, it is important for art education to be aware of this impact:

Art education could do with less modesty and suggest to the employability checkers that they could learn something from its experimental cognition, instead of being intimidated by them. (…) It is not art that is faced with a major challenge in the light of education. It is the educational bureaucracy that is faced with a major challenge in the light of art4

Not only professional dance training in higher education but also pre-professional schooling is challenged to prepare students for this increasingly versatile profile of contemporary dance artists.5 In order to become a professional dancer, it is often assumed one must start early with training and this trajectory should become increasingly intensive and specific. But these assumptions do not guarantee success in becoming a professional contemporary dancer today. This is partly due to the complex profile of a contemporary dancer as described above, but also to the multiple dance education trajectories one can take (also at an early age). In this respect, there is not necessarily a seamless convergence between the different stages in a person’s education, which might cause fissures in terms of approach, technique, or research. Given this often irregular progression, educational institutions should ask how to deal with the sometimes substantial differences within the (pre-)education of young dancers. How can dance education recognise these differences and at the same time foster the artistic and personal growth of students? In the current field, training that starts at an early age and focuses exclusively on a specific technical dance style may prohibit rather than nurture a successful path towards contemporary dance. It might well be that a beneficial trajectory for contemporary dance education is not so much about how much or what one has danced before but how dance and movement research have been approached and what teaching methodologies the student has experienced.

Against this background, it becomes clear that there is a pressing need to recognise the challenges for (pre-)professional dance education today as well as to develop a possible and – more importantly – a shareable framework that could help to instigate changes in contemporary dance pedagogy. This need for self-reflection has spurred us, the authors of this text, to embark on a two-year research project titled ‘The Role of Vocabulary in Contemporary Dance’, which we conducted at the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp (RCA) under supervision of Annouk Van Moorsel between 2016 and 2018. This project enabled us to probe our own experience with practice-based research in dance education in relation to a wider perspective on dance pedagogy in national and international (higher) art education institutions.6 More specifically, our research has been directed by some of the following breaches we believe are particularly acute in contemporary dance education: curricula run the risk of becoming out of date when it is not sufficiently acknowledged that the lexicon of contemporary dance is continuously in evolution; some established teaching methodologies, evaluation and feedback systems are less supportive of the current contemporary dance profile; there are significant gaps between the end and starting competences of different levels in (pre-)professional dance education and the demands of educational institutions are not always aligned with the daily reality of dance artists who (want to) teach.

The primary context for this research has been the RCA – mainly because we both work there as teachers, but also because dance education at the RCA has changed significantly over the past decade. However, while efforts have been directed at easing the transition from a bachelor education into the professional working field, bridging the gap between a pre-professional training and a professional bachelor programme in dance, as well as between the bachelor into amateur dance teaching still presents challenges. Perhaps one of the biggest changes the RCA has introduced during this period – initially under the artistic direction of Iris Bouche and now by Natalie Gordon and Nienke Reehorst – has been to start working with what might be called a ‘nomadic body’ of teachers consisting of practising contemporary dance artists. These teaching artists7 bring their own evolving dance practice and research as part of the core content and methodologies of the bachelor dance programme. This team is nomadic in that it continually fluctuates: rather than a more or less permanent staff delivering regular classes over an extended period of time, artists and researchers now come to teach for shorter yet intense periods of time.

There are several reasons for choosing to work with a nomadic body of teachers. A first one is the practical availability of these teaching artists: as they have their own active artistic practice, they cannot teach for several months when in rehearsal or on tour. More importantly, however, is that students benefit from being immersed in one particular bodily language and terminology for an intensive period before being challenged to transfer, integrate, or contrast that knowledge with the language of another artistic practice. Further benefits are that students are already networking whilst in education; experiencing real-life situations with artists who are not necessarily educators; gaining up-to-date course content; and participating in representative forms of collaborative practice. At the same time, there is a coordination challenge to keep tuning this fluid team to the core identity of the programme and to plan ahead whilst remaining flexible for unexpected artistic teaching opportunities.

Both the changed profile of contemporary dance artists and the specificities of dance education, as offered at the RCA, raise a set of important questions that we wanted to address in the mentioned research project and which we will also reflect upon in the present article. If flexibility is a core principle of being a dance artist as well as of dance education, we must ask how we can create education systems that are sufficiently delineated and simultaneously flexible enough to keep evolving and to match current needs and trends in the dance field. And to what extent should these education systems adapt to new tendencies? Could we develop learning structures that can evolve within themselves, rather than having to keep inventing new methodologies to reach new artistic or societal demands? Some institutions are developing their curricula to have their programmes resonate with the ongoing changes in the identity of dance or the performing arts. But instead of having to invent new systems every time there is a societal or artistic shift that we must learn to recognise, our intention was to create a certain degree of flexibility within the learning system itself so that it can adapt alongside a shifting landscape whilst conserving relevant essences from existing educational models. We wanted to develop a curriculum that reflected current demands for arts education and supported the development of new thinkers and makers to become the dance artists of tomorrow.

Ways of teaching dance

My most valuable learning experiences were those where my teacher was not telling me what to do, but rather enabling me to find my own solutions, (…) setting a rhythm between mastery and exploration, problem-solving and problem-finding.8

This statement from the famous sociologist Richard Sennett confirms what we also noticed in our more-than-twenty years of dance teaching. Some of the most successful dance education appears when both parties are no longer interested in a classical expert-novice relationship, but are more invested in multiple roles happening within a class situation, such as a teacher shifting roles from expert to mentor and even to ‘learner’.9 If a fluctuating learning relationship happens in a mutually deserved and respectful manner, it is at the core of raising self-aware, constructively critical, communicative, and autonomous artists (and young people) today. With this knowledge, how could dance education be organised to serve future autodidact dance artists, who are proficient and critically self-reflective about their own practice and teaching methods? When dance artists enter the field, they need the skills to voice an opinion in both a constructive and authentic manner; to evaluate themselves in realistic terms; to develop a language to talk about their own and other people’s work; to steer their practice through intrinsic necessity; and to develop and translate that practice to multiple contexts for a variety of target groups. Our task in dance education is thus to stimulate the autodidact qualities within future dance artist students, so that we, as teachers, no longer hold the only key to their evolution as artists.

In the light of these exigencies, classic methodologies of teaching and evaluating in dance do not manage to cover the range of skills to be developed in today’s dance artists (and young adults in general) anymore. By ‘classic methodologies’, we mean teaching exclusively by demonstration, while evaluations are mainly result-based and the appreciation of the students’ outcome happens by numbers ranked in relation to one another. A rather caricatural sketch of this classic approach in dance training would proceed like this: teachers prepare all the dance steps to be learned, they demonstrate them as the archetype to work towards in class and, in doing so, implicitly set a definition of what dance is and is not. They might be the only one giving appraisal or critique on the execution of these steps. They will ask for focus and quiet in class. These teachers will likely create a dance work for public performances and select the students who will stand in front on stage and get a more prominent role. If a dancer is in pain, the answer might encourage them just to get through the performance. The parent in this caricature is keen to appreciate this specific movement material, which is possibly performed ‘on’ the music, in unison, with a narrative and in a gender-normative costume. Even though this sketch might seem exaggerated or even outdated, it is a reality that students might still encounter to a greater or lesser extent during their (pre)professional dance education.

© Boris Bruegel

Historically, the main focus of dance classes has often been on developing craftmanship. In some dance education the emphasis indeed still lies on just teaching steps. This approach, however, is increasingly being challenged.10 Many dance teachers today are no longer merely repeating the traditional teaching style they might have been trained in themselves. And if it still appears, their intention is not to undermine the learning process of their dancers by placing craftsmanship as a main goal. Instead, they are often searching how to complement existing curricula with their own practice and exploring new methodologies to encourage different talents of their students, including not only their technical competences as craftspeople, but also as performers, collaborators, artists, or researchers.11 Classic systems of evaluating are also being challenged by focusing more on verbal or written feedback instead of comparative rankable grades.

Nevertheless, traditional teaching methods do continue to persist, which impels one to ask – yet without ignoring the possible benefits – what effect does this have on young dancers’ minds and bodies? Most importantly, having a constant external movement example reinforces prevailing standards for body types and aesthetics. This means that students will be incited to aim for a goal that lies outside of themselves and, in many cases, out of reach. The use of play and humour in a learning situation can turn this into a productive challenge. But when translating this image to one’s own body is framed with negativity, high demands, and limited freedom, it can be a dangerous learning experience for a young adult. It still happens that audiences, teachers, and even doctors assume that one has to have a certain body type to be a dancer.12 One could say that in contemporary dance a wider variety of bodies is embraced, with the role division between a man and a woman also being less stereotypical. But still it can be questioned whether the majority of the performer types we see on stage is representative enough of the diversity in society today. Some (contemporary) dance companies are recruiting artists who come from different backgrounds or other disciplines and have more diverse life experiences, a different performance attitude, or a non-normative body type. For example, Jan Martens’ dance performance PASSING THE BECHDEL TEST, which the Belgian choreographer created in 2018 for the production company fABULEUS, set a range of youngsters on stage that were refreshingly ‘un-performative’ at moments. They would casually sit down, mumbling words more to themselves than to the audience, barely allowing us to witness their inner thoughts. This kind of work may create more resonance and recognition for today’s young audiences, rather than solely the athletic, ambitious, good-looking, smart, eloquent performers that still seem to be the ideal in many dance castings. If dance has the ambition to engage in different kinds of societal discourses – also the ones including failure, ugliness, old age, and disease – it is essential to include movement research regarding these subjects in dance education.

Working with an archetypical example means a continual confrontation with right and wrong ways of thinking. We have experienced in our own teaching practice at RCA that students coming from an educational background focused on the mere teaching of technique, have more difficulties to engage in researching their own experimental ways of moving. They often have a more limited image of what ‘dance’ means and can stand for, including what its societal function can be. They are often the people waiting for the teacher to tell them what to do instead of starting from their own interests. The fear of being wrong restricts their attempts at experimentation. In the contemporary dance field today, however, a dancer is often also a collaborative maker, a source of inspiration, participating in creative discourse and being asked for feedback on multiple levels. This attitude is hardly fostered by the one-directional feedback on which classical teaching methodologies often rely. In these models, it is the teacher who takes the power to value a person’s practice. This relies on the teacher’s willingness and capacity to give feedback in order to progress. If the teacher does not see potential in a student, neither might the student. Multidirectional feedback, on the other hand, means the teacher ceases to be the central figure in a learning trajectory and self-reflective learning by the student is encouraged.

There are many different methods to establish this multidirectional learning environment. Task-based teaching, instead of demonstration-based teaching, is one of the possibilities. In this approach, a teacher can, for example, ask students to prepare an exercise and teach it to the others in class; to give feedback to each other; to formulate own goals at the beginning of a year, potentially based on the feedback received at the end of the previous year; to teach a dance phrase to be rechoreographed as a travel phrase, to turn it into a duet, to be analysed in terms of movement qualities, or to perform with different qualities or spatial orientation, etc. Once this route is taken by the teacher, the possibilities become extensive.

In this respect, what might be the biggest challenge in dance education could also be its greatest advantage. Typical for dance artistry is that its content is inevitably transient: not only is dance a domain in which new physical material is continuously created, this material is also repeatedly transferred between bodies that each have their own individual qualities and idiosyncrasies. As the art of dance is one of constant (co-)creation, the material is always morphing in the memories of specific bodies. This elusiveness has definitely fostered a certain flexibility that prevents a historicist stagnation of dance and which at least partly explains why contemporary dance continues to pursue its experimental orientation. Regardless of expertise or dance style, however, classroom methodologies often remain unsupportive of the artistic practice. The question thus becomes how to embrace the flexibility inherent to dance while still ensuring a common ground that can help to steer dance education into new directions. An important key to this lies in the role of language in dance.

Communication and vocabulary

One of the reasons people often give for why they choose for dance is because this is the language in which they can proficiently express themselves. This has created a comfort zone for many, assuming that words are not needed and the body is the vessel of communication. But dance is suffering from the side effects of this non-verbalising attitude. And dance educators still tend to pay insufficient attention to training the communication skills of their students, even though we live in a world where the ability to speak up often stands for visibility and rights. Luckily, however, many dance artists today are increasingly becoming verbal experts on their allegedly non-verbal artistry. And this is crucial.

© Sara Claes

The importance of language for dance (education) manifests itself in making students aware of the specific vocabulary and terminology used to describe movement and choreographic practices, as well as stimulating their personal communication and feedback skills. Yet for these crucial aspects of their training, students currently still depend too much on the individual talents and personal interests of the teacher. It is not visible, shared, or practised enough in the field. On top of that, teaching artists are often teaching in several different contexts, which poses a considerable challenge for how feedback and evaluations are communicated to students. In order to ensure a sufficient degree of coherence and clarity for both students and teachers in a single institution, it is necessary that there is at least a minimal common ground, a language that can be shared and relied upon for giving direction to a student’s development within a particular programme. Of course, one can advocate that a student benefits from receiving similar information through a variety of terms, perspectives, or communication styles. But for evaluation in particular, a total openness can create a confusing babel for students. At RCA, transferring knowledge and skills across subjects has become a very important focus in the dance programme. In order to achieve this transfer, students are encouraged to integrate knowledge across the curriculum, while teacher teams try to facilitate this by referring to one another’s content and language use.

We propose that dance education for all age groups can benefit from implementing a well-considered strategy on vocabulary development for dance. As the title of our two-year research project ‘The Role of Vocabulary in Contemporary Dance’ indicates, a key starting point for us was that the development of vocabulary to talk about different aspects of dance should become an integral part of the training of dance students. In dance education, a lot of time can be spent on teaching and practising steps, with the result that little time is left to stimulate a discourse about it. We are, as mentioned, also very conscious that the diversity within teaching teams inherently leads to a kaleidoscopic vocabulary. Our aim with this research is therefore to nourish this rich diversity, while also working towards a more unified communication within dance education. More specifically, we want to contribute to the acknowledgement of transferable skills; to the development or implementation of constructive feedback systems13 for training and practice; and to creating the tools to dialogue about work and to share ideas. These objectives can only be realised if we have an adequate vocabulary to build a critical discourse on the dance experiences of both artists and spectators. For this reason, one of the overarching aims of our research and its outcomes is to stimulate teachers and students to give dialogue and discussion a more prominent role in and outside the classroom.

If, as we have been arguing thus far, dance education should acknowledge the importance of language, it is not only because it serves the artistic, personal, and intellectual development of (future) dance artists, but also because language is a vital means to help solidify the field. There is no doubt, for instance, that Belgian contemporary dance is internationally acknowledged and present on stages and in higher education worldwide. Yet despite this broad acclaim, it is still a vulnerable domain, both within the arts and from a societal perspective.14 In this respect, it is important to realise that an artistic practice like dance becomes more validated, recognised, known, and (financially) supported when it is accompanied by a critical discourse through books, articles, films, documentaries, or interviews. Yet Belgium does not have a particularly strong tradition of writing on dance, especially not from a dance artist’s perspective. Texts are mostly written by critics or scholars who comment or theorise about dance from a spectator’s viewpoint and in primarily dramaturgical terms, yet not from an embodied dance artist’s experience.15 While the benefits of this discursive framing are obvious, it does not provide the full story. The often silent role of the dance artist partly contributes to the precarious position dance continues to have in Belgium, not so much in terms of appreciation yet definitely when it comes to funding and education. It is striking, for instance, that Belgium is one of the last European countries to inaugurate an official and institutionally recognised Master in Dance programme.16 As a consequence of all this, very few dance artists are currently taking up decision-making positions such as policymaker, programmer, and academy director, which clearly impacts how the field develops, both in terms of artistic practice and education.

Even though skilful communication and adequate vocabularies furnish dance with important tools to gain visibility and legitimacy, language can also be a considerable hindrance for dance artists to pursue their professional career, especially when they want to take up teaching jobs. More than ever, English has become the lingua franca of the dance field. This obviously increases the opportunities for students, teachers, and performers to study or work at schools, companies, and all sorts of dance-related institutions worldwide. What is often less recognised, however, is that preprofessional dance education still happens mostly in the language of the country or region where it is taught, which raises significant challenges for professional dance artists graduating in a country of which they do not speak the language. In the case of RCA, for example, the dance programme has a steady influx of talented incoming students from various nationalities as there are no formal language requirements to enter the programme, except for a sufficient mastery of English. A problem occurs when graduate students have an interest in teaching on a pre-professional level but do not know Dutch well enough to enter the Educational Master in Dance programme at RCA. This is a difficult issue that is also relevant to various schools in other countries that seek a fluent circulation between professional dance education and pre-professional training. It raises the question whether language courses need to be a compulsory part of either the bachelor or teacher training programmes. Is this even possible when there is still the need to develop language and communication skills to talk about dance specifically? Could we teach contemporary dance classes in English in a similar way to how French is used for classical ballet?

The problem remains hitherto unresolved. As far as dance education in Belgium is concerned, gaps between pre-professional dance training and the professional field currently remain standing. In this scheme, pre-professional dance education continues to be served by a Dutch or French-speaking dance community which represents only one part of the active Belgian dance field. Even though we find it important to raise this language issue, it requires a more structural policy that goes well beyond the scope of both our own research and this article. Instead of wanting to solve the difficulties arising from language differences, the intention with our research was rather to take a step back and to look at the role of language and vocabulary in dance on a more fundamental level. We wanted to ask how we could align the different terminologies, learning outcomes, and methodologies of teaching artists from various backgrounds within single institutions. In other words, while our research started from the question of what role vocabulary plays in contemporary dance education, it soon turned into a methodological issue addressing the foundations of teaching dance.

Dansstaalkaarten

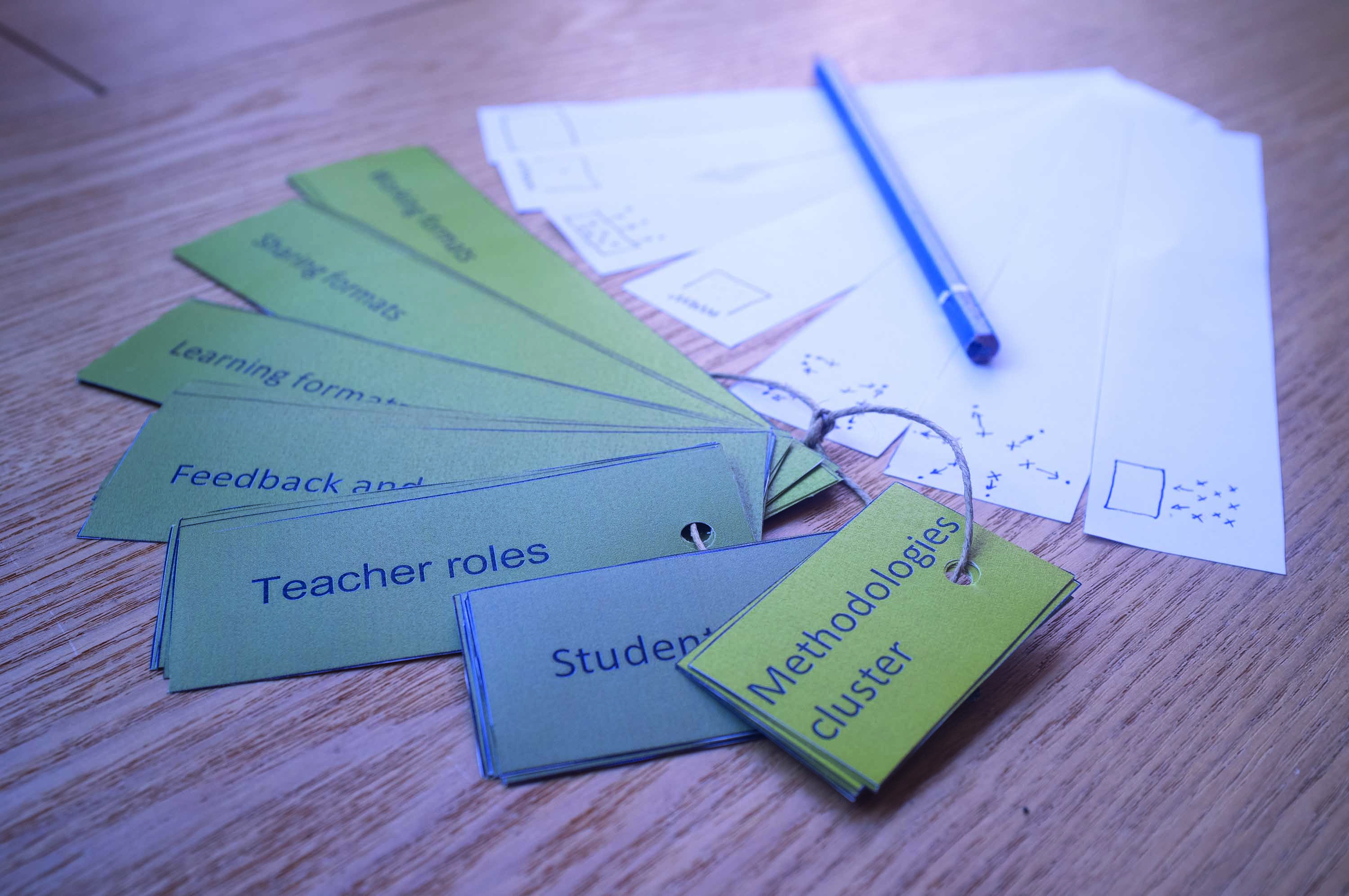

To support the evolutions that contemporary dance education has been going through in recent years became one of the primary motivations of our two-year research project. We specifically wanted to respond to the growing need to update existing curricula and teaching methodologies. The primary way to tackle this issue was to analyse our own (teaching) experience and to combine it with the previously mentioned ‘best practices’ that already proved their value.17 Probably the greatest challenge, then, was to translate the insights we derived from this mainly reflective research into an overall approach that could support dance and arts education on different levels in a manageable and hands-on manner. This resulted in the creation of what we have termed the dansstaalkaarten (dance sample cards). These are, quite literally, a set of cards that together provide a flexible framework to help dance educators to develop curricula; to articulate transferable skills for feedback; and to provide insight into different aspects of dance content and methodologies. In each case, the aim is to encourage more supportive learning experiences.18

The dansstaalkaarten function as a sample palette with coloured cards that allow dance educators to combine the different components of a class in order to reach diverse learning goals. The format stimulates play and experimentation. The different components are gathered under three main headings: I. Starting Competences and Considerations; II. Content; and III. Methodologies. Part I (Starting Competences and Considerations) aims to raise awareness of the various factors that should be considered prior to teaching a group, such as individual student attributes, the teaching environment, and the broader (educational) context. Part II (Content) provides an extensive list of topics that incorporates, among others, physical skills, spatial awareness, personal development, contextualisation, movement qualities, musicality, research and collaboration. Part III (Methodologies) explores a wide range of methodologies for teaching, learning, sharing, communicating, giving and receiving feedback, and evaluating. Taken together, these three parts can help a teacher plan and devise a class and/or course. But the dansstaalkaarten can also serve multiple other goals: they can be used by students to determine their interests and activate their involvement in their study trajectory; provide an overview of themes to cover and plan in time; challenge certain patterns of teaching; provide new methods for giving and receiving feedback; drive content; help make assessment more transparent; bring awareness of other skill areas to be developed; and provide a record of topics covered so that future teachers can continue their own planning from there.

We strive to be as comprehensive as possible by offering a broad collection of potential components of a dance class, regardless of style. We aim to leave artistic and stylistic freedom to the teacher to respect their background. Because in current contemporary dance education the individual artist is responsible for developing the content and format of a class, we have chosen to no longer create a curriculum with a list of style-specific steps, but with a range of parameters that can help to structure the content and format of a contemporary dance class. An explanatory lexicon of the terminology used in the dansstaalkaarten will be included both in English and Dutch to provide supplementary explanations where required in order to make them as accessible as possible, which is important in light of the language issue we raised above. In short, the dansstaalkaarten are designed in a format that wishes to support individual freedom, while offering stimulating frameworks and references for the dance educational field.

The dansstaalkaarten were originally conceived as an inspirational tool for teachers in part-time contemporary dance education who were searching for updated curricula. In the course of developing them, however, it became clear that the terms, structures, and approaches we came up with are both general and flexible enough to be transferable to a broader range of dance and arts education, regardless of level, style, or discipline. The dansstaalkaarten offer a tool for educational institutions to acknowledge and reinforce existing strengths in their current teaching practice, to gain insight into the capacities or ambitions within a teaching team or individual teachers and to develop a clear profile of their (dance) education. As we described in the previous section, today’s reality is that teacher teams are often very diverse in profile, so the challenge becomes how they can share one vision. One possible way to achieve this could be by discussing teaching methodologies as much as content, also when recruiting. The dansstaalkaarten are aimed at feeding exactly this discussion.

Working with the dansstaalkaarten to design classes, however, does require the creative investment of a teacher and may challenge teachers who utilise the more traditional teaching methodologies we referred to earlier. Since there will not be a list of steps to teach, the format wants to encourage teachers to analyse and reflect upon their own style-specific skills and teaching perspective. The toolbox can spur teachers to incorporate previously unexplored content and methods of teaching through selecting components included in the cards that are less familiar to them. Hopefully it will offer teachers who have not been trained in current contemporary dance methods some bridges toward this field, whilst respecting their original expertise. This in turn can contribute to developing the analytical, linguistic, reflective, and verbal skills in their students.

Our concern throughout this article and, more broadly, our research, has been dance education, but we obviously recognise that not everyone taking dance classes is destined to become a professional dance artist. But when dance education is willing to cover the full spectrum of skills to which it can give access, the impact of such training extends far beyond the world of dance. Encouraging young people to train, verbalise, research, experiment, reflect, share, present, develop an opinion, dialogue, interact with society, and remain open to change can only benefit them throughout their whole education and formation as participants in society. Although the ambitions are high, we hope that because the content of our research could be shareable on many levels, it can help the dance field to continue developing a loud and clear voice of which to be proud.

+++

Natalie Gordon and Caroline D’Haese

Natalie Gordon and Caroline D’Haese are teachers in the Bachelor of Dance programme (choreography, improvisation, Bartenieff Fundamentals, Labananalysis) at the Royal Conservatoire Antwerp (RCA) and were part of the team developing the new ‘Master in Dance’ programme. Both have their own professional dance practice: Natalie through her work with Retina Dance Company/Filip Van Huffel and Caroline as a performing artist with Reckless Sleepers Company, as well as making, performing, and teaching her own work. Natalie is also the Artistic Coordinator the Bachelor of Dance programme, alongside Nienke Reehorst, and she teaches at the Dance Teacher Training Department.

Footnotes

- We have chosen to use the term dance artist, which is more encompassing than singular labels such as dancer or maker or teacher or performer or researcher. The inspiration for this term comes from theatre, where the traditional division between maker or actor is similarly becoming obsolete. In our understanding, the notion of a dance artist acknowledges more emphatically the various roles dancers take up throughout their career (often simultaneously). ↩

- For more on the current socio-economic position of artists in the region of Flanders, see the report of the research project “Loont passie? Een onderzoek naar de sociaal-economische positie van professionele kunstenaars in Vlaanderen”, 2016, www.kunsten.be/dossiers/perspectief-kunstenaar/kunstenaarcentraal/2626-loont-passie-sociaal-economische-positie-van-podiumkunstenaars. English version, “Does passion pay off? A study of the socio-economic position of professional artists in Flanders”, www.flandersartsinstitute.be/research-and-development/socio-economic-position-of-the-artist/2789-does-passion-pay-off-a-study-of-the-socio-economic-position-of-professional-artists-in-flanders, accessed 10 June 2019. For a comparative study on the precarious position of dance artists in Brussels and Berlin, see Van Assche, Annelies. Dancing Precarity: A Transdisciplinary Study of the Working and Living Conditions in the Contemporary Dance Scenes of Brussels and Berlin. Doctoral dissertation, Ghent University, 2018. ↩

- When using the term ‘society’ in this article, we mean society from a cosmopolitan West-European perspective. ↩

- Hertmans, Stefan. “Masters of Unpredictability.” Teaching Art in the Neoliberal Realm: Realism versus Cynicism, ed. Pascal Gielen & Paul De Bruyne, Valiz, 2012, p. 143. ↩

- In Flanders, there are different educational structures offering pre- and professional dance training. Next to training in private schools, there are different forms of formal education, including ‘Deeltijds Kunstonderwijs’ (part-time arts education), ‘Kunstsecundair Onderwijs’ (Secondary Arts Education), and ‘Hoger Kunstonderwijs’ (Higher Art Education). ↩

- Inspirational partners, models and ‘best practices’ for this research have been amongst others: a.pass, DAS Arts, modular teaching systems in the U.K. and USA, and www.idocde.net for documenting teaching practices internationally, accessed 27 July 2019. ↩

- ‘Teaching artist’ is the term used within the Teacher Training Programmes at RCA. It is usually defined as follows: ‘A teaching artist (artist-educator) is a practicing professional artist with the complementary skills and sensibilities of an educator, who engages people in learning experiences in, through or about the arts.’ www.creativeground.org/faq/what-teaching-artist, accessed 19 August 2019. ↩

- Gielen, Pascal & Barend van Heusen. “A Plea for Communalist Teaching: An interview with Richard Sennett.” Teaching Art in the Neoliberal Realm: Realism versus Cynicism, ed. Pascal Gielen & Paul De Bruyne, Valiz, 2012, p. 37. ↩

- New educational models use the term ‘learner’ rather than student to acknowledge the multiple directions in which learning can happen. See, for instance, the frame of reference for quality in education: www.mijnschoolisok.be/professionals/wat-is-ok/resultaten-en-effecten, last accessed 9 August 2019. ↩

- A clear indication of how classic teaching methodologies are being challenged is the new Decree for Part-time Arts Education (‘Deeltijds Kunstonderwijs’), issued by the Flemish government in 2018. An important part of this decree consisted of the updating and reformulation of the learning outcomes and end competences for part-time arts education. For more specific information on these changes, see onderwijsdoelen.be and onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/wat-verandert-er-in-het-deeltijds-kunstonderwijs. Specifically for dance, these new learning outcomes are significantly more in line with the profile of contemporary dance artists as described in this article. Other notable (research) projects that were initiated by the Flemish Ministry of Education in support of arts education are: “Kunstig Competent” (by Luk Bosman and his team, www.g-o.be/kunstigcompetent_jun16 and “Artistieke Competenties” (by Erik Schrooten and his team, see artistiekecompetenties.blog/. In addition, the website mijnschoolisok.be was created as a supporting frame with guidelines and best practices for qualitative education aimed at several educational parties, including students, teachers, parents, and principals. All mentioned websites accessed 27 July 2019. ↩

- These five roles have been developed in the Kunstig Competent model by Luk Bosman and his team. They are now one of the foundations for teaching in Flemish Part-time Arts Education (Deeltijds Kunstonderwijs). See Schrooten, Erik & Luk Bosman, Fundamenten, 2016, artistiekecompetenties.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/fundamenten-def1.pdf, accessed 27 July 2019. ↩

- In her thesis Top Athletes or Artists?, Caroline D’Haese notes that ballet exercises often have a short duration and explosive nature, training the short, bulky, and fast-twitch type of muscle fibres (known as type 2), in a way similar to short-distance runners. The desired body image for female ballet dancers, however, generally results from training the lean, long, slow-twitch muscle fibres of type 1, which is only acquired by long, low-impact, durational physical activity, like marathon runners do. Consequently, the aesthetic of ballet is de facto in contradiction with the actual training of these dancers; or it is at least not attracting the matching body types for the type of sport it actually is. In contemporary dance, the aesthetic range is much wider. However, also in this case, if training continues to focus on what has not yet been achieved, this can be – in combination with genetic vulnerabilities or particular life experiences – so mentally challenging that, anno 2019, there are still (young) dance students suffering from mental diseases, such as anorexia and bulimia nervosa. These disorders are triggered not only by a desire for a specific body type but by a much more complex combination of factors. Dance that continually focuses on improving one’s body might fuel this desire even more, or might attract people who are already concerned with body image. For more, see D’Haese, Caroline. Top Athletes or Artists? Natural Nutrition, Health and Lifestyle Advice for Dancers, Thesis for the European Academy, Ghent, 2005, pp. 58-60. ↩

- For our work on feedback, we have been drawing on the DAS Theatre Feedback Method, which is an open-source feedback system developed by Barbara Van Lindt (artistic director of the programme from 2008 to 2018) and philosopher Karim Bennamar. It is one of the current cornerstones for peer-feedback at RCA and other higher arts educational institutes. More information can be found here: www.atd.ahk.nl/opleidingen-theater/das-theatre/feedback-method/#c75577, accessed 19 July 2019. Other inspiration on feedback came from Hattie, John & Helen Timperley. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research, vol. 77, no. 1, 2007, pp. 81-112. Another important resource has been the observation methodologies of the American choreographer Anna Halprin. See: Halprin, Lawrence. The RSVP Cycles: Creative Processes in the Human Environment. Braziller, 1969. ↩

- See, for instance, Van Assche, Annelies & Rudi Laermans. Contemporary Dance Artists in Brussels: A Descriptive Report on their Socio-economic Position. S:PAM (Ghent University) and CeSO (KU Leuven), 2016, biblio.ugent.be/publication/8536528/file/8536531.pdf, accessed 28 July 2019. ↩

- There are of course exceptions to this and Belgian journals are increasingly incorporating artist’s writings. Choreographer Martin Nachbar’s contribution to this FORUM+ issue testifies to this development. Other examples include, Vickers, Katie & Albert Quesada. “A Conversation between Katie and Albert.” Documenta. Special issue ‘State of the Art’: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives on Theater Studies in Flanders, ed. Timmy De Laet, vol. 35, no. 1, 2017, pp. 213-231; or Barba, Fabián. “Het Westerse vooroordeel over hedendaagse dans.” Etcetera 156, 2019, pp. 16-28. ↩

- The Master in Dance is a new programme beginning in 2019-2020 at RCA. It is the first time in Belgium that dance students will be able to obtain an official master’s degree. This is an important and long-awaited development that will finally eliminate the inequality in terms of employment and salary of dance teachers. ↩

- See note 6 and 13. ↩

- The first phase of devising the dansstaalkaarten on paper and receiving feedback from a select group of teachers and educational experts has already taken place. Next, we are aiming for a longer test and feedback phase with a pioneer team of teachers and experts. This will then stimulate more revision before making final adjustments to incorporate into a publication with a dansstaalkaartenbox and illustrative website. ↩