This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 26 no. 3, pp. 64-71

Conducting silence. The use of conducted and measured silences in Michael Maierhof’s guitar orchestras.

Thomas R. Moore

Koninklijk Conservatorium Antwerpen

Silences are an essential part of music. When rigorously measured, like in Michael Maierhof’s Zonen 6 for guitar orchestra, silences can structure an entire composition and help the listener make sense of a piece. Their artistic usage also has a dramatic affect on the conductor’s role and performance practice. Exactly 75% of Michael Maierhof’s Zonen 6 for guitar orchestra can be described as composed and metered soundscapes played and performed by seventeen guitar players. The other 25% of the piece is comprised of measured and conducted silence. In this article, Thomas Moore will delve in the artistic use of these silences and examine the manner in which they frame the soundscapes and help create structure. The use of the conductor throughout these silences will also be considered, as well as the possible ways in which this affects the guitarists’ performance and the audience’s perception of the piece.

Stiltes zijn een essentieel onderdeel van muziek. Wanneer stilte nauwkeurig wordt gemeten, zoals in Michael Maierhofs Zonen 6 voor gitaarorkest, kan deze een hele compositie structureren en de luisteraar helpen om een stuk zin te geven. Het artistieke gebruik ervan heeft ook een dramatische invloed op de rol en de uitvoeringspraktijk van de dirigent. Precies 75% van Zonen 6 voor gitaarorkest van Michael Maierhof bestaat uit gecomponeerde en uitgemeten soundscapes, uitgevoerd door zeventien gitaristen. De andere 25% van het stuk bestaat uit afgemeten en gedirigeerde stilte. In dit artikel peilt Thomas Moore het artistieke gebruik van deze stiltes en onderzoekt hij de manier waarop zij de soundscapes omlijsten en helpen structureren. Ook het nut van de dirigent(e) tijdens deze stiltes wordt overwogen, net als de manieren waarop de dirigent(e) invloed uitoefent op de uitvoering door de gitaristen, en de perceptie van het stuk door het publiek.

Silences are an essential part of music. They frame sounds and structure melodies. They can add suspense, humour, or solemnity to a composition. Silences make jingles and ragtimes hip. They have also been strategically applied in iconic masterpieces such as in the opening measures of Beethoven’s (1770-1827) fifth symphony (1804-1808) and in the second movement of his ninth symphony (1824). Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) riddled his l’Histoire du Soldat (1918) with cleverly timed silences. As an aesthetic statement, silence can also be effective, such as in Yves Klein’s (1928-1962) Monotone-Silence Symphony (1949), written in two movements for any large ensemble or orchestra. The first movement is a single twenty-minute D-major sustained chord followed abruptly by a twenty-minute silence.1

The satirical piece Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man (1897), by French writer and humourist, Alphonse Allais (1854-1905) is prefaced with these lines,

‘The author of this funeral march was inspired in its composition by the principle, accepted by everyone, that great sorrows are silent. Since great sorrows are silent, the performers should concentrate solely on counting bars, rather than making that obscene racket which deprives the best funerals of their solemnity'.2

The piece is twenty-four blank measures, and if it were ever to be performed, would consist of musicians marching and counting silently. Beethoven, Stravinsky, Klein, and Allais each provide examples of measured silences. The silences are to be performed by musicians, structure themes, melodies and pieces, and create tension that is observable and palpable to an attentive audience.

Zonen 6 for guitar orchestra (Zonen 6) by Michael Maierhof (1956) contains long and rigorously measured silences. Like the silences in the examples above from Beethoven, Stravinsky and Klein, they are not only perceived aurally, but visually as well. A conductor delineates their duration and intensity. In the pages below, the reader will be presented with a brief explanation of the score with specific attention paid to the different types of silences (rests) employed in Zonen 6 and in Maierhof’s compositions in general. The usage of tempo will be analysed and the manner in which the guitarists count the rests and the possible effects this might have on them and by proxy, the audience, will be discussed. Criteria for the utilisation of a conductor in this piece are demonstrated. I also present arguments determining that the presence of the conductor is no secondary phenomenon of the music, but instead is an integral part of the piece and a performance thereof. Finally, comparable pieces by Maierhof are detailed.

It is as though Maierhof has slowed down and zoomed in on a melody. Each individual note of that macro-melody now takes minutes and the rests and breaths have become suspenseful, pregnant silences.

The analysis of Zonen 6 detailed below was performed within the context of my PhD research, titled “Redefining the role of the conductor in new music” and under the auspices of both the University and Conservatoire of Antwerp. The artistic use of the conductor by the composer, Michael Maierhof was brought into focus in an attempt to clarify and define the conductor’s role as well as the consequences thereof for the performance practice. I was fortunate enough to have had the opportunity to conduct the premiere of the 2018 revised version of Zonen 6. Together with the student-guitarists of the conservatoire, I plunged into, explored and discovered new sonorities in Maierhof’s unique mechanical, Gerausch sound world.3

Based on experiences in my artistic practice, I hypothesized that the various uses of a conductor in new music can be divided into five criteria.4

Below I will discuss the four applicable criteria found in Zonen 6. One of those criteria, especially prominent in this work, is the artistic use of universally recognisable conductor’s movement repertoire. I have systematically studied and tested the same criteria in five other relevant works: Charles Ives’s fourth symphony (1916), John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957-1958), Simon Steen-Andersen’s AMID (2004), Alexander Schubert’s Point Ones (2012), and Alexander Khubeev’s Ghost of Dystopia (2014, rev. 2019).

Specifics of the piece

Michael Maierhof’s (1956) Zonen 6 was written in 2007-2008, and then revised in 2018 for the guitar class at the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp. Originally the piece was written for an amateur ensemble and Maierhof took the opportunity to ‘complete the piece now that he had a much better ensemble for it’.5 The revised edition, orchestrated for seventeen prepared acoustic guitars, was premiered on the 17th of March 2019, at deSingel in Antwerp, Belgium. This article will refer only to the revised score that was published by the composer in 2018.6

Maierhof’s Zonen 6 is comprised completely of guitar-playing techniques that are unique to the piece and have been created by the composer himself. In order to explain these techniques, Maierhof has written an extensive legend. Prior to the premiere performance of the revised edition, the composer was present at the first rehearsal to introduce his piece to the performers, answer questions, demonstrate the techniques and explain the sounds. (The legend to Zonen 6 can be viewed via the following link: appendixes.)

The time signature throughout the entire piece is five-four (5/4). According to the composer, this is an attempt to lend no specific beat any predetermined strength.7 For example, within the Western art music tradition, and when the time signature is a four-four (4/4) measure, it is common to consider the first and third beats the strong beats and the second and fourth beats the weak or backbeats. By choosing the time signature 5/4, the composer endeavours to avoid this predetermined distinction. A measure with the time signature 5/4 can be subdivided in several different manners, for example: 1 + 4, 4 + 1, 2 + 3, and/or 3 + 2. This variable manner of subdivision can generate an ambiguity between strong and weak beats. In Zonen 6, the composer uses this ambiguity advantageously to ensure that no single beat, simply by its location in the measure, is presumptively granted either of these binary distinctions.

Typically, rests are used to notate silence in music. Maierhof has differentiated between two different types of rests that are utilised throughout his piece. The first type of rest is an ordinary, conventional rest. Maierhof calls it a Vorbereitungs-pause. As the name suggests, these rests are deployed by the musicians to physically prepare themselves and their instruments for their next entrance. The second type of rests is designated Stilstand-Pause and looks like normal rests except they are adorned with a downwards pointing arrow. During a Stilstand-pause the musicians may not move. The composer describes their stillness not as a freeze. A freeze would imply that all things come to a momentary stop. However, the guitarists should instead sit still and be attentive, prepared and focused for their next entrance. These rests, as will be explained further, are used to continue, conclude or initiate tension essential to the piece in its entirety. Throughout the remainder of this article, when the author refers to silences, only the Stilstand-pauses will be considered.8

The guitarists have been instructed (in the legend) to seat themselves in a circle surrounding the audience. While this in itself is not extremely out of the ordinary, the position in which the conductor is placed is remarkable. The conductor has been instructed to position him- or herself behind the audience. He or she is visible to the guitarists yet invisible to the audience. The traditional concert role of the conductor in which he or she performs for two audiences, the musicians and the “paying public,” has thus been torn asunder.9 The public can only perceive his or her performance vicariously through the musicians.

Analysis method & measurable trends

During the introductory session of Zonen 6 (a portion of the first rehearsal of the revised version), Maierhof made it a specific point to demonstrate the manner in which he would like the collective Stilstand-pauses to be conducted. He chose measure 22 as an example. The indicated tempo for this measure is ten beats per minute (bpm). Applying a simple math equation: sixty (seconds to the minute) divided by ten (bpm) results in six seconds per beat (the beat in this case is a quarter-note). Six seconds per beat multiplied by five beats (5/4 time signature) equates to thirty seconds. In other words, measure 22 is thirty seconds long: thirty seconds of ‘measured silence’.10

Maierhof’s specificity in regard to the measured silences leads to a deeper review into the use of tempo in this piece in general and how it relates to both the measured silences and the tutti sections. By applying the same simple math equation described in the paragraph above throughout the entire piece, a chart could be created which examines and compares parameters for each measure and section of Zonen 6. These parameters are: tempo, duration of the beat, number of beats, and duration of the measure. Every measure was classified as a solo (1) or ensemble (2) measure, as well. The total duration and number of beats per section can be found in this chart: appendixes

In this visualisation of Zonen 6, the white blocks indicate the rests/silences and the blue blocks indicate the ensemble sections. This to scale flow-chart illustrates the form of the piece and the framing of the ensemble sections by the measured rests.

A study of the above-described systematically generated chart reveals certain trends and characteristics of Zonen 6. One such noticeable characteristic is the compelling balance between silences and ensemble playing. The piece, when performed with rigorous and strict adherence to the indicated tempos, is exactly fourteen minutes and thirty-six seconds long. (From the second beat until the ending. The first beat is adorned with a fermata and is used pragmatically. The prolonged first beat, once shown by the conductor, allows the guitarists to prepare themselves for the start of the piece.) The tutti soundscapes total eleven minutes and the solo silent sections combined are three minutes and 36 seconds long. In percentages, this results in a balance of 75% tutti soundscape and 25% solo silence.

A second noticeable trend is that in the ensemble sections the ratio between the number of beats per section and the duration of that same section appear to be more or less linked throughout the piece. This can be explained by referring to the composer’s choice in tempos. Throughout the piece, the ensemble plays in the relative region of sixty bpm (beats per minute). Sixty (seconds to the minute) divided by sixty bpm equals one second per beat, in other words, a ratio of 1:1.

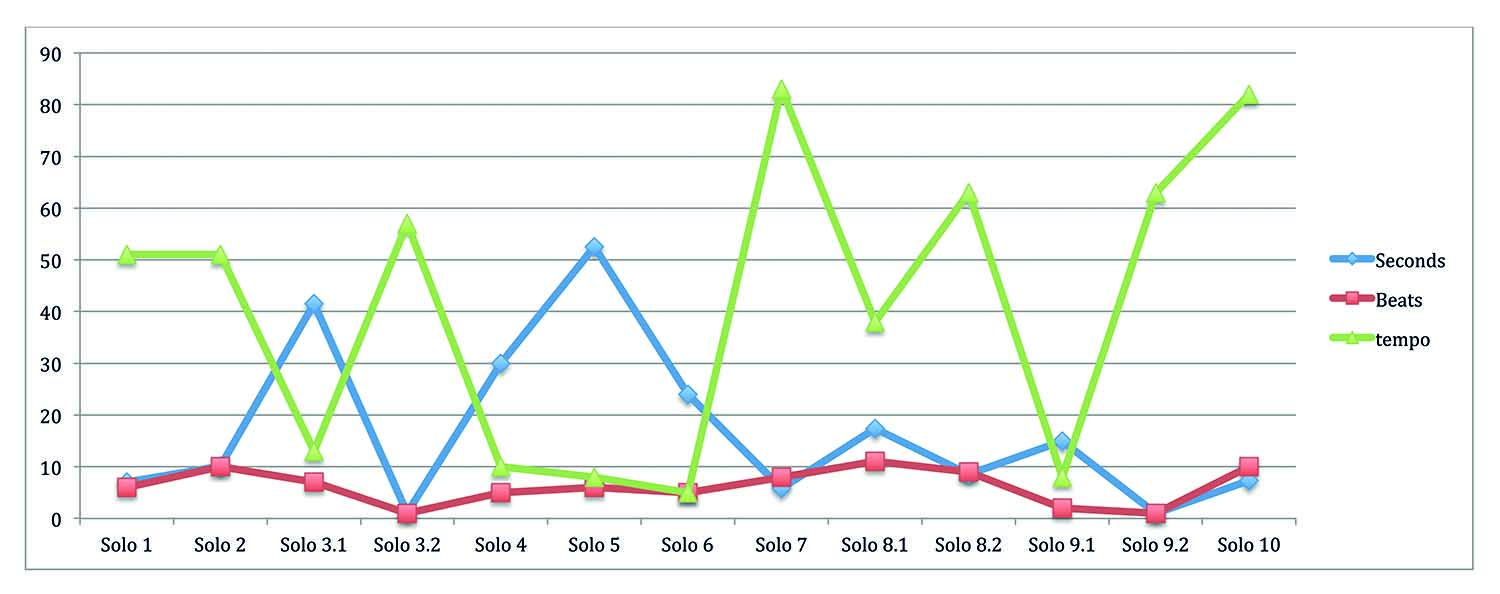

The solo conducted silences reveal something completely different. In those sections, drastic variations on the ratio between the number of beats and the durations thereof occur. (See Illustration 1 below.) For example, Solo 6 (measure 45) has two beats and is twelve seconds long, a ratio of 1:6 and Solo 7 (measures 57 and 58) has a ratio of 1:0.72.

This chart shows the conducted silences. In red, the number of beats per section is rather consistent. The green line indicates the wildly fluctuating tempo and the blue line is the effective duration of each section.

In a personal interview, the composer explained, ‘Silences are used to clean the ears of the listeners and prepare them for the next course’.11 Based on the data shown above, it is conceivable that the (conductor’s) audience is, metaphorically speaking, cleaning their ears by being asked each time to ʻcount to ten.ʼ The widely variable tempo at which the audience must do that metaphorical counting is then relative to the amount of cleaning necessary to prepare the listener for the next section. By applying different tempos and durations the composer has granted each silence a specific artistic weight.

Structure

Zonen 6 is structured around striking, original and rhythmical soundscapes that are individually bricked in by measured silences. The piece follows a free form and alternates between tutti-ensemble-played soundscapes and conducted measured silences. The entire form can be seen in the chart attached to this article in the appendixes. Although the piece is not balanced in regard to the duration of time spent in conducted silences and tutti passages, it is equally divided between the amount of sections dedicated to each: there are ten sections of solo-conducted measured silences and ten tutti passages as well. In total, Maierhof indicates thirteen tempos across the (intended) fourteen minutes and 36 seconds of his piece.

According to musicologist Andrew Kania, ‘various kinds of silences occur during musical performances and on musical recordings. [They can be] distinguished between measured and unmeasured silences’.12 Unmeasured silences can be understood as those that frame pieces, such as the silence between movements in a symphony or the time between the last note of a piece and the commencement of the audience’s applause. These are spontaneous and improvised silences that originate with the performer. Measured silences, on the other hand, are rests with a composed and indicated duration. They have a consistent value (in regard to duration) and are essential to melodies. Imagine listening to your favourite jingle without the rests. The jingle would probably be very difficult to recognise should you negate or change the value of the rests. Measured silences can be understood to frame melodies and make them comprehensible to the listener.

When the definitions above are applied to Zonen 6, it can be concluded that all of the Stilstand-pauses (except the pragmatic first beat) can be classified as measured silences. The durations of these rests are fixed by a specific tempo indication, they lack fermatas and no expressive indications such as rubato, espressivo, accelerando or ritartando are present in the piece. Furthermore, they are not simply counted out by the guitarists but visually displayed by a conductor, thus unifying the performance of these rigorously measured silences.

Maierhof has framed each tutti section (soundscapes) in Zonen 6 with measured silences. Each soundscape is completely filled with sound. Individual musicians have individual rests, but as a whole, the ensemble only collectively rests during the Stilstand-pauses. It is as though Maierhof has slowed down and zoomed in on a melody. Each individual note of that macro-melody now takes minutes and the rests and breaths have become suspenseful, pregnant silences. To visualize this, a flow chart has been made to scale. Each silence is indicated with a transparent block and the numbering corresponds to the solo-conducted silence as detailed in the aforementioned chart (see appendix). The soundscapes have been indicated with blue blocks and each letter corresponds similarly with that chart. The flow chart shows that the measured silences quite literally frame the soundscapes: they are present before, in between and after every ensemble section. Like rests in melodies, the silences give structure to the soundscapes and make the piece comprehensible in its entirety.

In an interview in 2013 with researcher and pianist Sebastian Berweck, Maierhof was quoted as follows, ‘Sound and silence have the same weight [in my music]’.13 I have shown above that theoretically this is indeed the case in Zonen 6. The measured silences are weighted individually depending on the amount of preparation (or time for reflection) required by the audience prior to, or immediately after, a soundscape. And we have also seen that the measured silences frame and create structure for the entire piece.

At this point in the article I would like to address the intended performance practice of these measured silences. The rests, their durations and amounts, are clearly described in Maierhof’s score and parts. Based on my own experience as a performing musician and as a conductor, I expected the guitarists to actively, though silently, count the rests in a similar fashion to the manner in which they actively and silently count while playing. My expectations were confirmed during the question and answer section of my initial presentation of the piece.14 The guitarists have also been instructed by the composer to sit still and not prepare (physically) for their next tutti-section, ‘nur der Dirigent weiter – only the conductor continues moving’.15 The performance practice of the measured silences thus includes silent counting and a strict lack of physical movement.

Various studies have shown that brain activity during silent counting, though different for every person, is in any case higher than while waiting, even attentively, for a pre-ordained cue.16 A performer’s silent counting is observable and palpable to an attentive audience. It creates a specific tension in both performer and observer. According to the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, tension (and the release thereof), is an essential characteristic of play.17 Putting Huizinga’s theories into practice, developmental psychologist Elly Singer too noticed an ever-present and crucial ‘tension [in her subjects] between play and normal life’.18 That tension between “real and play” when applied to performance art is what creates and holds the audience’s concentration. According to sociologist Erving Goffman: ʻWanneer iemand een rol speelt, verzoekt hij zijn waarnemers impliciet om de indruk die bij hen gewekt wordt serieus te nemen. Hun wordt verzocht te geloven dat het personage dat zij waarnemen werkelijk de eigenschappen bezit die het lijkt te bezittenʼ.19 As has been argued above, the measured silences are integral to the performance of Zonen 6. However, for the audience to appreciate the role of silence in Zonen 6, the guitarists and conductor must perform them with a level of seriousness and tension that will enrapture and hold the public’s concentration. Furthermore, the tension that the guitarists’ silent performance creates appears to be the composer’s intention.

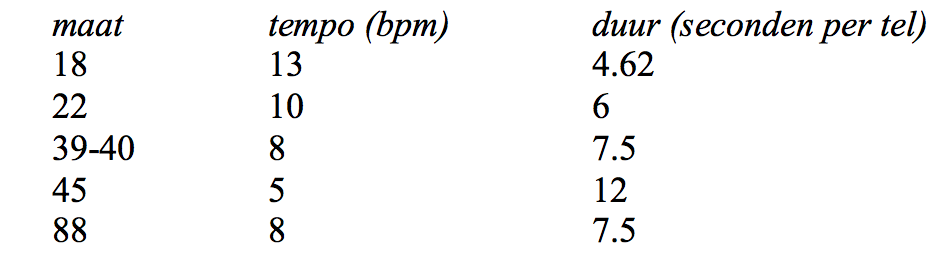

Zonen 6 frequently changes tempo during the measured silences. For example, in measures eighteen and nineteen, both within Solo 2, Maierhof adjusts the tempo twice, inducing subtle changes to the level of performed tension. The ensemble begins the silence at 51 bpm (beats per minute), changes to thirteen bpm and finishes the solo at 57 bpm. The composer has anticipated a different ‘level of energy from the guitarists during each [performed] tempo within the silences’.20

The durations of these tension-creating silences vary greatly throughout the piece. The shortest measured silence is 7.06 seconds and the longest is 52.5 seconds. The number of beats per measured silence, however, has a narrower margin.

The shortest is three beats and the longest is eleven. It follows then that the duration of each beat must vary and some beats are therefore quite long. The longest beats in the piece are found in the measured silences:

The conductor’s physical gestures unify the guitarists’ performance of these rigorously measured silences. The seventeen guitarists sit in a circle surrounding the audience with the conductor positioned behind the audience. In this manner, the audience, seated and all facing in the same direction, is unable to see the conductor or his or her movements delineating the counted rests. The conductor’s visible solo performances during the silences are for the sole benefit of the guitarists. Maierhof has also requested that these measures (the measured silences) be conducted in a “normal”, or conventional manner – however the motions are ‘extremely slow’.21 The continuous motion of the conductor’s arms, as opposed to a static conducting style, creates and sustains a tension in the conductor’s audience (the guitarists.) Four demonstration videos have been embedded below. Two of the tempi listed directly above are each presented twice below: the first time in each tempo is static and the second, continuous. The videos demonstrate the build-up and release of tension in the static form and the sustained tension created in the continuous form.22

Static – 13 bpm: youtu.be/3WNey4wPujY

Continuous – 13 bpm: youtu.be/ooQeWIdlWes

Static – 5 bpm: youtu.be/apiNq8qet68

Continuous – 5 bpm: youtu.be/Ue5SwUMqxTM

In Zonen 6, the conductor displays the exactly measured silences to the guitarists, and the guitarists, unified by the conductor, silently and actively count the rests. The silent counting generates the required tension and the conductor’s gestures sustain it. It can therefore be argued that even though the audience cannot see the conductor’s solo performance during the measured silences, his or her presence is apparent and appreciable vicariously through the guitarists to the general audience members.

Measured silences conducted

The title of this article describes the silence found in Zonen 6 by Michael Maierhof as both measured and conducted. In this section of the article, the presence and function of the conductor during the measured silences and the piece as a whole will be discussed in greater detail. The reasons for his or her utilisation can be divided into the following four categories.

Economy

Though possible in theory, many of the ensemble passages would be extremely difficult to perform without a conductor. The guitarists (and in the case of the premiere of the revised version of Zonen 6: student-guitarists) must focus a great deal of their attention on simply producing the sound world unique to this composer and even this piece. Much of the movements necessary to create the sounds are in unison or in groups. However, many of the sounds have special internal rhythms that are different in each guitar and sponge combination. On top of that, the guitarists do not sit in a traditional ensemble U-form. They are spread out in a circle surrounding the audience. This will cause some of the performers to be in a position in which they are unable to see their colleague-guitarists, thus making it even more difficult to synchronize their timing.

By employing a conductor, the concert organiser (in the case of the premiere of the revised edition: the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp) has given the guitarists the ability to pass on to a central person their responsibilities for timing, entrances and endings. The conductor, as an external figure, can not only take the form of a living metronome, but also a unifying dominant point that every player agrees to follow and refer to for all music making excepting their own sound production. Should the musicians have to fix all things internally, the required rehearsal time would be prohibitively expensive in time and treasure. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the concert organiser has availed itself of a conductor in Zonen 6 for economic reasons.

Artistic and substantive input

The role of the conductor in Zonen 6 is similar in one fashion to what we find in John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957-1958). In both pieces, the conductor has a movement role that is not directly associated with the production of sound. In Cage’s piece, the conductor is strictly limited to fulfilling an artistic movement role and his or her gestures are restricted to the simulation of a clock. In Maierhof’s piece, however, the conductor is granted/burdened with much more freedom of gesture. Also, in Zonen 6, both during the soundscapes and the measured silences, normal conventional conducting is required. Neither is true of Concert for Piano and Orchestra. However, during the conductor’s solos (the measured silences), although universally recognisable conventional conducting gestures are employed (by the conductor), these sections contain slow movements and are performed in silence. The extremely slow tempos at which they are performed require a control of movement to sustain tension that exceeds the conventional expectations of a conductor. During these measures (the solos), the conductor’s role is also that of a movement artist.

Huizinga details certain elements that are prerequisites for an audience to accept an action as “play” or performance. For example, play, amongst other characteristics, takes place in a specific location, has specific rules and traditions, and ‘tension and then solution must also be present’.23 A performance of Zonen 6 takes place in a space recognised and utilised as a concert hall. The performers can expect that traditions will be respected and rules applied that are inherent to a concert given within the Western art music tradition. And Maierhof’s piece and the intended performance practice thereof by the conductor, as shown above, create and maintain tension during the solo conducted measured silences. For these reasons, both the highly controlled movement repertoire and the sustained tension, it can therefore be argued that the composer utilises a conductor in Zonen 6 for his or her artistic and substantive input.

Audience & musician perception

As argued above, the audience can indirectly perceive the conductor’s presence (standing behind them and therefore invisible, unless the audience should frequently turn around) via the guitarists. The measured silences, framing the ensemble passages, are counted out both silently in the heads of the guitarists and displayed by the (slowed conventional) gestures made by the conductor. All performers have agreed to submit to the conductor’s timing in regard to the duration of the measured silences (for the entire piece, as well) and follow his or her (practised and) performed subdivision of each measure into beats. Focused together, their counting matches the conductor’s. The tension created by their silent attentiveness, detailed above, helps to maintain the audience’s attention to the performance, as well. The conductor’s slow-motion movements in this manner grant artistic weight to the composed and measured silences.

A performer’s silent counting is observable and palpable to an attentive audience. It creates a specific tension in both performer and observer.

According to the sociologist Erving Goffman, most solo roles have multiple audiences.24 In the case of the conductor, we have the audience, seated in the auditorium or tribune, ready to view and listen to a performance. For the conductor, the performing musicians are also his or her audience. This is inherent to the role of the conductor. However, in Zonen 6, Maierhof has placed the conductor in a unique position. He prevents the audience from viewing the conductor like they normally would during a conventionally set-up concert. Only the guitarists can see the conductor. His or her visible performance has suddenly become for their sole benefit, especially during the measured silences.

For these two reasons, and accepting that the guitarists can also be the conductor’s audience, it can be argued that the conductor is utilised by the composer for the influence his or her gestures have on the perceived perception of the audience.

Visual component: Movement repertoire

As discussed earlier in this article, the silences between, before, and after the tutti passages in Zonen 6 are exactly measured. They are composed in the form of measures with a specific time signature. The tempo is indicated in an exact bpm unit and there are no expressive indications. It has also been argued that the silences have artistic value as frames for the ensemble passages, similar to the way measured rests frame notes in a melody. And finally, it has been argued that the silences themselves carry an artistic weight, generating a tension essential to the performance as a whole.

The composer has indicated that these silences are to be conducted in a conventional, continuous manner using universally recognisable conducting gestures. It can therefore be concluded that a conductor has been utilised in Zonen 6 for visual reasons. The conductor’s movement repertoire is not a secondary phenomenon of the music. It is an essential and integral part of the piece and the performance thereof.

Comparable pieves by Michael Maierhof

The use of structured and measured silence in Maierhof’s compositions is not unique to Zonen 6. For example, in his pieces Exit F for eight musicians and four hot air balloon pilots (2013) and Schwingende Systeme B for double quartet (2015-2016), measured silences are frequently used to frame the solo, duet, quartet and tutti passages in these pieces. Similar to Zonen 6, the musicians in these two pieces also have Stillstand-pause and Vorbereitungs-pause. This appears to be a fixture in Maierhof’s compositions.

The extremely slow tempos at which they are performed require a control of movement to sustain tension that exceeds the conventional expectations of a conductor. During these measures [the solos], the conductor’s role is also that of a movement artist.

Maierhof has utilised a conductor-as-soloist in his previous works, as well. Two such examples are Schwingende Systeme A for alto saxophone, English horn, trombone, table double bass, piano, three object players and percussion (2015-2016) and Splitting 12 for solo conductor and electronics (2003/2005). In the former, the conductor has a fifty-seven second explicitly choreographed solo. (See link to score excerpt.)25 His piece Splitting 12 is for conductor solo. The performer sits behind two transparent objects, facing the audience and using both hands, and traces conducting patterns across the surface of the objects.

The reason why we can set Zonen 6 apart from these two previous works is twofold. Firstly, the conductor in Zonen 6 is placed behind the seated public, making him or her invisible to them or in the least, unobtrusive. The conductor’s traditional two-part audience is, in this fashion, restricted to only his or her fellow performers: the guitarists. They are the sole recipients of his or her visible performance. In Schwingende Systeme A, the conductor performs for both the seated public and the fellow musicians. And in Splitting 12, the conductor is alone on stage and in full view of the seated public.

Secondly, though extremely slow, the conductor in Zonen 6 only employs universally recognisable conducting patterns to display the passage of time during the measured silences, the “solos”. As is apparent in the linked illustration and the links provided below, that is not the case in Schwingende Systeme A. In this piece, the movements themselves become the artistic material for a short time. And in Splitting 12, it could be argued that the conductor’s movements themselves have become a subject of the entire piece.

Links:

- Nadar Ensemble, Michael Maierhof: schwingende Systeme, B - Nadar Ensemble, 2017.

youtu.be/C6kDSN2MPyY. Last viewed: 10 March 2019

- Löser, Christof M., Michael Maierhof: splitting 12 for conductor (2003-05), 2015.

www.youtube.com/watch. Last viewed: 10 March 2019

- Nadar Ensemble, Klarafestival 2017: EXIT F - Nadar Ensemble, 2017.

youtu.be/HPFypgkAcV8. Last viewed: 10 March 2019

Conclusions

In this article the Stilstand-pauses in Zonen 6 have been labelled as both measured and conducted. The rigorously measured nature of the silences has been shown to carry artistic weight that falls into two categories. First, the measured silences act as a frame for the played soundscapes, creating a structure for the entire piece. And second, the manner in which the guitarists and conductor execute the silences generates a tension that allows the audience to wilfully accept the actions displayed before them as performance.

It has also been shown that the presence of the conductor during a performance of Zonen 6 is not simply a secondary phenomenon of the music. The presence of the conductor is an economic and artistic choice made both by the concert organiser and the composer. His or her presence is integral to the piece for reasons that can be divided in four categories. (1) A conductor has been utilised as a movement artist and thus for his or her artistic and substantive input. (2) The piece would be too difficult or prohibitively expensive to perform without a live external figure displaying the passage of time and so a conductor is employed to lead the ensemble and structure the piece. (3) The conductor has also been instructed to use conventional conducting gestures (movement repertoire) to structure the framing, artistically weighted and measured silences. And finally, (4) the desire by the composer for the audience to perceive an artistic weight (equal to that of the audible passages) in the measured silences requires a conductor focusing and unifying the performing guitarists.

I must admit that conducting such long silences seemed at first glance to be a futile exercise. However, the study above and experience garnered from conducting Zonen 6 have proven otherwise. As we have seen, rests are essential to music and help makes sense of themes, melodies and pieces. It is vital that all members of an ensemble play the audible notes together. However, just as important is the unification of the silences. Imagine the beginning of Beethoven’s fifth symphony with a non-unified and ambiguous first quarter note. The central theme of the entire first movement would be unrecognisable. As in Zonen 6, the conductor performs the first note of the fifth symphony alone, striking an intense downbeat that unifies the orchestra’s collective measured silence, from which the iconic four note opening theme springs to life.

+++

Thomas R. Moore

studied music performance at Indiana University (1998-2002) and the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp (2004-2007). He is currently a member of Nadar Ensemble and works as a researcher and doctoral student at both the Royal Conservatoire and University of Antwerp.

Footnotes

- Kennedy, Randy. “A Sound, Then Silence (Try Not to Breathe.)” The New York Times, 17 October 2013. ↩

- Whiting, Steven Moore. Satie the Bohemian: From Cabaret to Concert Hall. Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 81. ↩

- The use of sounds as musical material which are normally associated with noise, such as multiphonic bangs, scrapes and scratches. (cf. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. Music and Discourse. Towards a Semiology of Music. Princeton University Press, 1990, p. 52). ↩

- The term “new music” refers to music that has been written since 1950 and in the Western art music tradition. This research revolves around the hypothesis that artistic directors, musicians and composers decide today to utilise a conductor in new music ensembles for reasons that can be divided into one or more of the following five criteria: (1) the artistic and substantive input of the intended conductor; (2) the presence of the conductor as subject is central to the piece; (3) economy (as in required or available rehearsal time, difficulty of the music, and tradition); (4) the perception of the audience of a piece, program, and/or conductor; (5) and/or the visual component/movement repertoire (the conductor’s movements are an integral part of the piece – both musically and visually, his/her presence is not a secondary phenomenon of the music. ↩

- Conversation with Michael Maierhof, 2018. ↩

- Maierhof, Michael, Zonen 6 for guitar orchestra, 2007-2008 / revised in 2018, self-published. ↩

- Conversations with Michael Maierhof, 2018-2019. ↩

- The Vorbereitungs-pauses are purely functional and have no extra artistic or musical role in Zonen 6. ↩

- Goffman, Erving. De Dramaturgie van het Dagelijks Leven: Schijn en werkelijkheid in sociale interacties. Erven J. Bijleveld, 2016, p. 116. ↩

- Kania, Andrew. “Silent Music.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 68 no. 4, Fall 2010, pp. 343-353. ↩

- Conversations with Michael Maierhof and Pieter Matthynssens, 2017-2018. ↩

- Kania, 2010. ↩

- Cassidy, Aaron & Einbond, Aaron. “Noise in and as music. University of Huddersfield.” University of Huddersfield Repository, ISBN 9781862181182, 2013. The note references the interview with Sebastion Berweck, pp. 131-144. ↩

- Moore, Thomas. “Silence & Noise,” open presentation on 15 March 2019, Antwerp, Belgium: deSingel. ↩

- I took the opportunity to test this expectation with the guitar class by asking the performing, student-guitarist, “What do you do during the rests?” The resounding response was, “count”. Prior to the question about counting the rests, the students had been thoroughly introduced to the term “measured silences” and its meaning in the context of the piece. ↩

- Maierhof, Michael, 2018. Maierhof wrote both the original German text and the English translation in the legend attached to the score. ↩

- Gruber, Oliver. “Effects of Domain-specific Interference on Brain Activation Associated with Verbal Working Memory Task Performance.” Cerebral Cortex, Vvol. 11, issue 11, 1 November 2001, pp 1047-1055. ↩

- Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Angelico Press, 1949, p. 10. ↩

- Singer, Elly. “Play and playfulness, basic features of early childhood education.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, vol. 21, no. 2, 2013, pp. 172-184. Her studies are on the play element in the educational development of children, however her remarks apply to adults as well. ↩

- Goffman, 2016, p. 27. Translation by Thomas R. Moore: Whenever someone plays a role, he or she implicitly asks his or her observers to take the created impressions seriously. They are asked to believe that the character they perceive actually possesses the qualities that it appears to possess. ↩

- Conversations with Michael Maierhof, 2018-2019. ↩

- Conversations with Michael Maierhof, 2019. ↩

- Huizinga, 1949, p.10. ↩

- Goffman, 2016, pp. 116-125. ↩

- Maierhof, Michael, Schwingende Systeme A, 2015-2016, self-published. ↩