This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 28 no. 3, pp. 36-43

On March 8, 2019, International Women’s Day, Yasaman Aryani carried a basket of white flowers into a women’s only metro car in Tehran and distributed them to the women there, wishing them a ‘Happy Women’s Day’. She was not wearing the mandatory veil while doing this, and her action was being filmed by a friend. The twenty-four-year-old activist ended up receiving a sixteen-year jail sentence for this act. But she was not the first or last woman to protest against the compulsory dress codes in Iran. The first protests began at the very start of the revolution, in 1979, when Sharia law was reinstated after fifty years, which stipulated mandatory veiling. In response, thousands of men and women came out to protest on International Women’s Day, carrying banners and shouting with raised fists. Within a week, mandatory veiling was lifted by the leader of the revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini, though it was later reinstated.

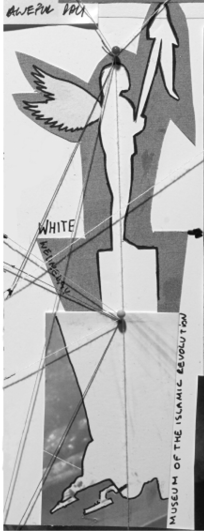

In December 2017, a woman climbed atop a utility box on a street corner in Tehran and waved her veil on a stick. This mobilized a large group of women to follow suit and form a movement. Filming themselves and putting their videos online, they became known as the Girls on Revolution Street and their actions as ‘White Wednesdays’, when women post photos of themselves dressed in white as a sign of protest.

In 2010, after the disputed 2009 Green Movement protests in Iran, Nasrin Sotoudeh, a human rights defender, was sentenced to three years in prison for no obvious reason. She was released in 2013. But in 2018, when a group of women in Tehran removed their hijabs in a street protest, they were charged with ‘violating public prudency’ and ‘encouraging immorality of prostitution’. The fifty-seven-year-old Nasrin Sotoudeh stepped in to defend these women. As a result, she was sentenced to thirty-eight years in prison, again with no clear reason.

What started out as a documentary/artistic approach to female figures and resistance in the Middle East became a personal investigation when I was able to return to Iran. Now, I could look into a revolution I had left behind. This transition from a relatively objective perspective to a personal one was transformative for me and for the final body of work. It is, in many ways, a return to the origins of my visual observations and to a more pronounced artistic approach.

My camera became a tool for holding on to what I could now finally physically see and touch. Even though I gave myself full artistic freedom to create this series of images, there was no need to stage any of the images at any point. The reality was far too interesting to fiddle with; things unfolded around me as if I were inside a movie, in which family members (dead and alive) appeared and disappeared. Present and past mixed together, dream and reality blended; it felt as if time no longer existed. For this part of my work, I did not interview experts in the field or activists. My aim was to move freely in various spaces and rely on family history, historic and academic research, and observations.

From the bruises on my body, I bloom,

I’m wounded but I bloom

by my very being

For I am a woman,

a woman, a woman.

If we sing all along,

shoulder to shoulder,

if we walk

Hand in hand and strong, we’ll be freed

from this wrong.

+++

Mashid Mohadjerin

is an Iranian-Belgian photographer and visual artist. Her work focuses on identity, resilience, political resistance and representations thereof. She finalized her PhD in the Arts, which is an artistic exploration of female figures and resistance from Cairo to Tehran, at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp in 2021. Mashid worked as a photographer for major publications while producing and publishing personal projects. Since 2017 she has published three books related to her research project.