This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 23 no. 1

Albrecht Huybrecht's Discovery

Albert Wise

Royal Conservatoire Antwerp

On Saturday 16 April, deSingel International Arts Campus will be presenting their Albert Huybrechts Discovery. An entire day is devoted to the life and work of Albert Huybrechts, an intriguing Belgian composer who died too young at the age of 39. Take a look at the photo: there he is with his much younger brother, Jacques. Albert was always in Jacques’ mind somewhere. He spent forty years trying to save the elder brother he adored from oblivion…

Op zaterdag 16 april brengt deSingel Internationale Kunstcampus de Albert Huybrechts Discovery. Leven en werk van deze intrigerende Belgische componist staan dan centraal. Kijk eens naar de foto: Albert Huybrechts, componist, te jong gestorven, en naast hem, zijn jongere broer, Jacques. Voor Jacques was Albert er altijd, ook veertig jaar na zijn dood, en hij maakte er zijn levensmissie van om Albert te redden van de vergetelheid…

Albert Huybrechts (1899-1938) was born in Dinant to a Flemish father, a cellist from Antwerp, and a Walloon mother, the daughter of a local tailor. Albert spent most of his life in Brussels, dying there at the age of 39 in 1938.

On 16th April 2016 deSingel International Arts Campus is to devote an entire day to the life and works of the fascinating Belgian composer Albert Huybrechts. There will be a concert of symphonic music, including the aptly named Chant d’angoisse, which we can perhaps see as his musical testament, as well as the rhythmically exciting Cello concertino. Highlights from his not inconsiderable chamber music oeuvre also feature on the day’s programme, including the Sonata for violin & piano, which won the prestigious American Coolidge Prize in 1926, and which ought for him to have been a springboard to fame and glory. Why it wasn’t, is probably as much due to his tortured personality as it is to the lack of recognition he received here in Belgium. Or so his brother Jacques claims.

Whether Jacques Huybrechts is right about this or not is one of the questions I hope to answer in my book Albert Huybrechts, testimony of a musician, which is to be published in the course of 2016, and which consists of a an English translation of Jacques’ French memoir about his brother as well as a critical analysis of Jacques’ very personal and very particular stance on the matter. He spent forty years promoting Albert’s works, publishing in 1982 a monograph in which very intimate details of the composer’s life, philosophy and artistic attitudes are revealed. He must have adored his brother.

On 16th April 2016 deSingel International Arts Campus is to devote an entire day to the life and works of the fascinating Belgian composer Albert Huybrechts.

Jacques work is for us today the basis for more or less everything we know about Albert Huybrechts’ biography. The Brussels film director Joachim Thôme spent six years working on his own imaginative response to Jacques’ version of the composer’s life, which appeared in November 2015 in the form of the magnificent docudrama S’ENFUIR, which deSingel will be showing at 12 noon on 16th April. Joachim has integrated crucial works from the composer’s oeuvre in his moving and gripping account of Albert’s life. He even arranged for a new recording of the Chant d’angoisse by the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège, who will in fact be presenting this work as the final item in their evening concert.

What follows is a short extract from the introduction, as well as two chapters from my translation of Jacques Huybrechts’ memoir.

In the royal library

The casual visitor to Brussels might be forgiven for not noticing the Royal Library. A modest monolith, it rises up on the south west side of the Mont des Arts, massive but retiring, a stone’s throw from the Central Station, if indeed one could throw a stone from the Central Station, which is buried metres under the ground by an extraordinary stroke of foresight on the part of the architects, which links rail connections to the north and south of the Belgian capital, and for which all Belgians, and our casual visitor for that matter, ought to be eternally grateful.

The Albertina, as the library is known colloquially, is a shy giantess who gives up her temple’s secrets only to those determined to discover them. Leaving the casual visitor outside in search of less abstruse entertainment, the determinedly curious enter through inconspicuously marked glass doors. Inside, the holders of a reader’s card may pursue their quest along a polished wood floor in the hushed silence of a broad corridor, lined as far as the eye can see with lockers, for therein must all coats, bags and sundry encumbrances be deposited. And so, the shoddy material paraphernalia of life left behind, you come to a row of lifts where you may wait patiently with your laptop and notebook under your arm, in the company of twenty or so others similarly equipped, like so many souls waiting for their crossing to Elysium.

The music department is on the fourth floor. Press a buzzer, and one of the guardians of this particular shrine will open the door for you to a high, spacious, light reading-room in which a dozen or so large oak tables are arrayed. There are lecterns and upholstered chairs, both much used. Outside a wall of windows, ordinary folk, far away, go about their ordinary business. The view to the gardens below is extremely agreeable.

You will have had the forethought to put in a request for the documents you want to read a day or two in advance, for the search for truth ought not to be too easy and anyway the custodian needs a little time to fetch them from the repository. After all, more than four million books are deposited here.

If you ask to see the Huybrechts archive, you will have to be a little more specific. There are many volumes and you may see only five at a time. You ask for the first five. You wait expectantly. After a time a trolley arrives. There are five boxes in very thick, blue-grey cardboard, heavy, built to withstand fire and flood, you feel, as you strain your elbows to put the first one on the lectern in front of you. Inside, a ring binder and plastic envelopes, all entries numbered meticulously by category and ordered by date. There are notebooks with harmony exercises, sepia photographs, concert programmes, newspaper reviews, extracts from magazines, transcripts of radio programmes and… letters. Letters to concert organisers, letters to publishers, letters to record companies, to magazines, to reviewers, to amateur music lovers, musicologists, librarians, conductors, violinists, cellists. And more often than not their replies too. The letters cover a period of perhaps fifty years, not in sudden bursts followed by long silences but steady and regular, a constant stream. Some are from or to the composer Albert Huybrechts but most are signed by or addressed to his brother Jacques.

Jacques Huybrechts

Jacques Huybrechts was the youngest of the three children and younger by seventeen years than his elder brother. In the middle came a sister. Jacques was to live on for nearly fifty years after Albert’s death in 1938. He married and had four daughters. He had a conventional job in the service of Diamant Boart, a Belgian international group active in the production and distribution of diamond tools and machines for the natural stone and construction industry. In his free time he painted and he corresponded. For the last twenty years of his life he worked on a memoir about his brother, which finally appeared in 1982. His daughters will tell you how he sat at the kitchen table every evening, a portable typewriter and a sheaf of papers in front of him, a PR-man and spin doctor avant la lettre, promoting his brother’s works, setting right the many misunderstandings about his life, making sure, in short, that no one forgot him.

In Jacques’ memoir nobody is spared, and least of all Albert. We see the composer warts and all, with all his arrogant intolerance, his disdain for those he so quickly branded as opportunist, his clumsiness dressed up as idealism, his pig headed self-denial, his inflexible and impulsive impracticality worn like a badge of defiance, his self-pitying defeatism, the enormous chip he carried on his shoulder. He was his own worst enemy. Their mother doesn’t fare much better in her younger son’s portrayal. He describes the family home in Anderlecht as a ghetto over which the mother rules, the father some four years dead, with tyrannical self-abnegation. Jacques’ description of how Albert caves in to her in Chapter V is at once heart-rending and exasperating. This is a family, dysfunctional but closely knit all the same.

Why did Jacques go to all this trouble? Why did he devote nearly three-quarters of his life to telling and retelling Albert’s story to all who were willing to listen? Does the key lie in the episode recounted in Chapter V, The flowers? In this scene from childhood an adult drama of recrimination is seen through the eyes of an eight-year-old, as little Jacques hides in his little corner and plays with his few toys while the grown-ups fight it out in the next room. Are his divided loyalties to haunt him for the rest of his life? These are speculations. Jacques himself is more specific. He outlines his point of departure in a long letter to the Canadian amateur musician and music lover Noël Falaise in April 1959. Falaise is a geography lecturer in the École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Montréal who listens to classical music voraciously in his spare time and plays the violin in an amateur string quartet. He and Jacques never in fact meet, but their correspondence spans a period of nearly ten years. Here is the passage in question:

I have now for many a long month been strongly absorbed in a short psychological essay about the case of my brother. The idea came to me after the concert on 1st July 1958. After reading the reviews I became aware of the general ignorance prevailing about the composer’s real personality, and realised that it was necessary to set the record straight. It might surprise you to learn that at the moment I remain the only person still able to bear witness to the man and the artist in his relations with the rest of the world.

The aesthetic problems on which everyone vainly dwells at such length pale into insignificance compared with the human problems which inspired his works and which marked them so intensely. One has to have been oneself one of the essential elements of these problems, to have been linked to their solution and furthermore to have had the inestimable privilege of fraternal affection to really feel everything which separates my brother from the kind of art reduced to a pure play of aesthetics or in short, the worthlessness of such a pastime. The problems which made him the man he was and which are embedded in his works: these we must reveal as clearly as we can and even crudely if this helps people to understand them. They are perhaps commonplace, but what is not commonplace is how he resolved them. That is where his humanity and the secret of his works is to be found.

Whether knowledge of a composer’s biography gives the listener insight into the inner meaning of his works is a moot point, as is indeed whether works of music can be said to have any inner meaning at all. Obviously some works of music have an ostensible meaning, or at least an ostensible function. A mass by Byrd, Palestrina, Schubert, Mozart is part of the liturgy of the Christian Church and in this sense has the inner meaning or intention of glorifying God and preparing the communicant to receive the Eucharist. The Matthew Passion is about the death of Christ and has the inner meaning or intention of intensifying the listener’s compassion for his suffering. Wagner’s Die Meistersinger is about a mediaeval singers’ guild and has the inner meaning of showing how musical inspiration transcends craftsmanship. Even Mahler’s second symphony is not only called the Resurrection Symphony but could be argued to be about resurrection too. But what kind of inner meaning does Huybrechts’ Violin sonata have? The Chant funèbre is called a funeral song but is it in fact an elegy? Can we listen to it without knowing that his father was a cellist and that his premature death was a ‘cruel stroke of fate’, as Jacques calls it, which was to change Albert’s life irreversibly?

Two brothers

As I write in 2016, Huybrechts’ prize-winning Violin sonata has found its niche in the repertoire. Recorded by some great violinists and played by many, it may stand alongside Ravel’s masterpiece in the genre, which was composed exactly contemporaneously, and is worthy of its place in the tradition of the Belgian violin school founded by Ysaÿe. This is as much due to the work’s intrinsic worth as to Jacques’ efforts on his brother’s behalf. Whatever Jacques’ personal reasons might have been, one cannot doubt the conviction and perseverance with which he applied himself to promoting and defending Albert’s music. As he writes, it was not time to compose more of which Albert was deprived by his untimely death: ‘A longer life wouldn’t have changed much. It was not time to write great works which he lacked, it was the ability and the means to make his way in the world.’

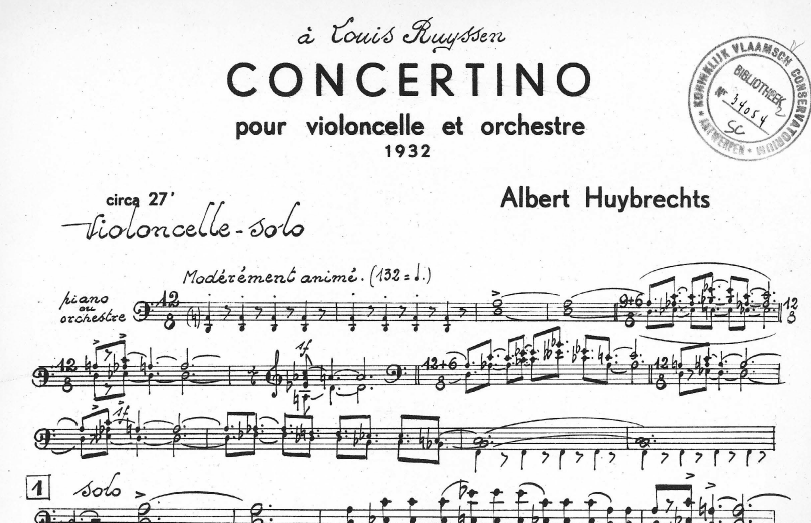

Albert Huybrechts’ Cello concertino (1932). CeBeDeM: Brussel, 1957.

Bibliotheek Koninklijk Conservatorium Antwerpen, KVC 34054

Even if he had lived longer, one wonders if his introverted and tormented personality could ever have got him better than a cold shoulder from the world at large. So far as his music was concerned, death and Jacques were the best things that could have happened to him. Perhaps I am being unkind. Jacques’ account of his life demonstrates, better than I can, how external factors combined with his obsessive and over-principled character forged a destiny from which there was for Albert Huybrechts no escape. Or if there was an escape, it was in music. As Jacques sees it, his music is his emotional autobiography, and memoir and music combined become a moving multimedia experience by two brothers whose fates were indissolubly joined.

What Jacques hoped for has, some fifty years later, actually come to pass and the music of Albert Huybrechts is in 2016 enjoying something of a revival. The label Cypres Records from Brussels is halfway through recording all of his works of chamber music, while the film director Joachim Thôme has just released the documentary film S’ENFUIR. In a year which has also seen the release of the documentary AMY about the tragic life of the British pop phenomenon Amy Winehouse, comparisons between Thôme’s and Asif Kapadia’s artistic visions are not out of place. Music and biography are inextricably linked in both, and Thôme’s highly imaginative achievement gives us this moving multimedia experience in concrete form.

As for Jacques’ motives, perhaps we should take the inscription on the first page of the memoir at face value: ‘À ma femme qui aura cru sans avoir vu.’ When he married in 1945, his brother had already been dead for some years. Jacques’ wife never saw Albert, never knew him, but after reading she will have believed, and will too perhaps have understood the personal circumstances which shaped the man she married.

As we close the last of the blue-grey boxes in front of us, in heavy cardboard built to withstand not only fire and flood but our inquisitive gaze too, as we replace it next to its companions on the trolley, slide our chair back under the broad oak table, glance once more out of the window to the gardens below where the ordinary people we are about to rejoin go about their ordinary business, we may well wonder at the ‘inestimable privilege of fraternal affection’ which we have just witnessed. It applies in both directions.

Without Jacques’ unceasing efforts, Albert’s music would surely be long forgotten. But even the greatest spin doctor cannot save second-rate art from oblivion. Huybrechts’ music lives on because it is touched by greatness, and we cannot help but be touched too by the infinite sadness of his life. With hindsight all our fates seem ineluctable but he seemed to have even fewer choices than most of us, we may well muse, as we collect our coats and bags from the Royal Library’s lockers and join the crowds surging down the steps of Central Station to wait for our rail connection, either to the North or to the South.

Translation of Jacques Huybrechts' memoir:1

Chapter IV Family Ghetto I

He had in him something quite exceptional, there’s no doubt about it. Everyone he associated with is in agreement about that. These were almost always relationships which he didn’t initiate with people he refused to confide in: chance encounters born of social necessity out of which friendship seldom arises and affection hardly ever. Maybe this explains why people practically never passed the stage of compassionate sympathy, desire to protect, regard for his moral integrity.

In Jacques’ memoir nobody is spared, and least of all Albert.

He never had a real companion in his whole life, someone with whom he could let himself go and to whom he could open his heart. Always he seemed distant and reserved, keeping company with no one, not even the neighbours he saw every day. If ever he were to involve himself or take part in something unreservedly, then it would be in secret and as if it were something to feel guilty about.

Music, his own mysterious music, was never other than a stage setting for or a contract with the passionate side of his nature, or at least what passed for a passionate side.

People who knew him, most of them without financial resources of their own, or badly placed to help him or support his aspirations, were more like accomplices than friends: some were devoted to the man but ignorant of the artist, others entertained misguided or infantile ideas about who he was. Of the musicians among them, many held views too distant from his, or were pupils too young to understand what he represented. They only had faith in the man, preferring to avert their gaze in the presence of an obscure reticence about more profound truths.

In reality the way his life unfolded was not normal, unless one is prepared to admit that music for him was not such an important matter, and that if he had had to choose, he would always prefer solitary stagnation.

To begin with there is the hidden fact, like all irrational truths hard to acknowledge, of the sacrifice he made of his life as an artist, not only in taking the full and unreserved responsibility of providing for his family, but also in submitting to an all too typical maternal despotism. This submission to duty is an affront to human decency, so evidently setting self-sacrifice against artistic ambition. Its gravity is fundamental. He was under an obligation to the world that judged him and which was willing to applaud the artist who offered up his life and even the life of others to his duty. No challenge could persuade him to turn his back on his moral obligations. Virtue, he felt, has nothing to do with art and he favoured his ethical integrity above his vocation as a musician.

Ever since adolescence he had felt somehow implicated in his parents’ marriage, and their quarrels, caused by the unspoken failure of their sex life, affected him deeply. Perhaps on the night before her marriage someone ought to have told the young bride something of the laws of existence before placing her ‘in the arms of the man who, henceforth, has the care of her happiness; it is his duty to raise the veil drawn over the sweet secret of life.’ No doubt she spent the night ‘anxiously awaiting the revelation she had partly guessed, the unveiling of love’s great secret’.2

That unveiling must have been quite horrific to judge by the eternal silence imposed on all matters of the flesh, whether explicit or implicit. This abnegation, observed by all of us, was so absolute that at the age of twelve I still knew nothing about the birds and the bees.

Physical love dared not speak its name; only in novels could we discover anything about it and only then in terms of the imagination of the novelists and thus in fact as a forbidden fruit only to be found in literature.

When the rowing started Albert stood up for his mother, she being the weaker party. This was the trap of pity into which he was inescapably to fall. It was not so much that he was actively entrapped, for of the two it was his father whom he loved in spite of the latter’s impulsive and extreme character. In his first youth he had been torn between his mother’s possessiveness, which turned him into a fearful child, and his father’s paternal authority, which resisted her hold on him. Albert was later to retain only good memories of his father. Of his mother he remembered only the worst.

When his father died in 1920 Albert became the sole support of a mother who had no strength of will, no hope, and no financial resources, of a younger sister of sixteen who had no idea what to do with her life and of a little brother of three.

Once the undertaker’s expenses were paid on the day of the funeral, they had no idea how they were going to eat the next day.

During father’s illness we had fought against the worst which was to come, but the worst which was to come was for Albert not so much the death of his father as the accession of his mother. As a wife she was always a victim. As a widow she was to become sacrosanct. In her distress she required support. In her unhappiness she was to demand devotion. The worship which emerged from his most elementary filial duty is from now on to define him completely in terms of both his own conscience and that of others. The family approves. Isn’t this what an exemplary son and brother ought quite naturally to do in the face of these unhappy circumstances?

No questions are asked about Albert the artist. First we have to live. Music of course he has to do because that is his profession and because he can’t think of anything else to occupy himself with. Once people have realised that that is a matter about which he admits no compromise, they let him get on with it as he sees fit.

In these complexities where pity and fear jockey for position, a new solidarity rises from our shared fate, a solidarity in which he who has the most to endure has the most to demand, in which the weakest must be rescued first. A spirit of the ghetto where mother is to rule for the rest of her life and which is to remain a mystery to the whole world.

Chapter V The Flowers

On Saturday 5th December 1925 two songs by Albert Huybrechts, Chant d’automne on a poem by Baudelaire and Les roses de Saadi, text by Deshorbes-Valmore, are performed by Mademoiselle Mergan, voice and Charles Scares, pianist, professor at the Brussels Conservatory, at a gala concert put on at the Belgian Radio Concert Hall by the Brussels division of the Amplion company.3 It is the first performance of the songs.

On my return from school a few days later I noticed a huge bouquet of red flowers on a piece of furniture.

It felt immediately to me as if some misfortune had happened, like a portent of doom.

There was a card attached to the bouquet, a visiting card from a young woman!

I don’t remember what was said at that moment but I can’t forget the sensation of high drama which this induced in my childish heart.

We’d never seen any flowers except the ones in our garden so this unfamiliar bouquet in our house was as frighteningly intrusive as someone armed with a gun.

I’d already heard Mother and Marcelle talking out loud in Albert’s absence about a twenty-franc coin found in the pocket of his dinner-jacket and about him repeatedly coming home late. I think they even went to spy on him at the corner of the road.

Now they were talking about ‘that woman’ with such a ferocity that I trembled with fear in my little corner while pretending to play. Our deep-seated destitution weighed on all this. Mother wept as she did the laundry and I didn’t dare breathe a word for fear of hearing Heaven knows what.

It felt as if a monster was prowling around the house, a monster which had to be kept out at all costs, otherwise we would be broken, cast out and thrown to the wind...

One evening, one dark winter evening, Albert came home late. We’d sat up waiting for him, Mother and I. She was silent and I was playing in my little corner and when he came in I went on playing.

I couldn’t say how it all started.

All of a sudden I heard Mother start shouting in a tone which made my blood freeze. She was sobbing and wringing her hands while he stammered, ‘But Mother, what’s the matter?’

I saw him get up to go and calm her but she jumped on him in the middle of the room, grabbing him by the hair and shouting in his face ‘Get out! Go with her then, walk out on your little brother, but just you wait till I get my hands on her, I’ll pull out her hair, I’ll gouge out her eyes...!

Quite distraught he spluttered ‘But Mother, but Mother!’

I still see before me this pitifully appalling scene in that dismal gaslight. I was behind the table the whole time scarcely daring to breathe. I was ashamed to have to witness such a scene.

When it was all over a heavy silence fell.

‘The little one is looking at me like a murderer.’

He was seated, hair unkempt, face distorted, and he looked at me with an indescribable expression.

‘Come and sit on my lap, my lad,’ he repeated.

I went toward him, my legs trembling, and laid my head against his chest. Then, his mouth in my hair, he burst into tears...

As I was going to bed I heard him say to Mother, ‘Let’s not talk about this matter ever again, if you don’t mind. I’ll write to her tomorrow.’ He kissed her and went into his room.

That was the end of it. My heart was filled with a tremendous calm and we never spoke of it again.

+++

Andrew Wise

Originally a British pianist, conductor and composer, Andrew Wise has taught in the vocal department of the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp (AP Hogeschool) since 2003 and is permanent pianist of the cello class. He teaches pianists who wish to specialize in coaching and accompanying opera and oratorio.

Footnotes

- A. Huybrechts, ‘Musicien prévenu de musique. Un dossier à instruire', www.alberthuybrechts.be/media/AlbertHuybrechtsUnDossierAInstruire.pdf (4 februari 2016). ↩

- G. de Maupassant, A woman’s life. New York 1923, p. 55: 'There are some things which are carefully hidden from children, from girls especially, for girls ought to remain pure-minded and perfectly innocent until the hour their parents place them in the arms of the man who, henceforth, has the care of their happiness; it is his duty to raise the veil drawn over the sweet secret of life. But, if no suspicion of the truth has crossed their minds, girls are often shocked by the somewhat brutal reality which their dreams have not revealed to them. Wounded in mind, and even in body, they refuse to their husband what is accorded to him as an absolute right by both human and natural laws. I cannot tell you any more, my darling; but remember this, only this, that you belong entirely to your husband… Jeanne lay still, anxiously awaiting the revelation she had partly guessed, and that her father had hinted at in confused words awaiting the unveiling of love’s great secret.' ↩

- Amplion is a brand of loudspeaker manufactured by Alfred Graham & Co. ↩