This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 23 no. 1

Depictions of reality. Past, present and future in a fictional framework

Nele Wynants

Université libre de Bruxelles, Universiteit Antwerpen

The artistic projects of Thomas Bellinck, Elly Van Eeghem and Chokri and Zouzou Ben Chikha share the characteristic that they depart from real historical sources. However, the result is no documentary theatre in its strict sense. The historical sources are put in a fictional context and are later analysed.

This article discusses several projects of these young, Flemish theatre makers and studies how they relate to a historical, social or political reality. By putting themselves in the centre of this reality and by engaging with it, these makers intentionally blur the lines between fiction and reality. They do not pursue an objective truth, nor a historically correct representation of the past, though they encourage other imaginations of the reality in which they take place. With their intervention, they try to make a social difference and reflect on models for the future.

De artistieke projecten van Thomas Bellinck, Elly Van Eeghem en Chokri en Zouzou Ben Chikha hebben met elkaar gemeen dat ze telkens vertrekken van reëel, historisch bronnenmateriaal. Toch is het resultaat geen documentair theater in de enge zin van het woord. De historische bronnen worden in een fictief kader gezet en uitgelicht.

Dit artikel bespreekt een aantal projecten van deze Vlaamse jonge theatermakers en onderzoekt hoe ze zich verhouden tot een historische, sociale of politieke werkelijkheid. Door plaats te nemen middenin die realiteit en ermee in dialoog te gaan, vertroebelen deze makers moedwillig de grenzen tussen fictie en realiteit. Zij streven geen objectieve waarheid na, noch een historisch correcte representatie van het verleden. Wel zetten ze aan tot andere verbeeldingen van de realiteit waarbinnen ze plaatsnemen. Ze trachten met hun ingreep een maatschappelijk verschil te maken en na te denken over modellen voor de toekomst.

Fictional museum

‘Today I visited the fantastic exhibition by Thomas Bellinck – I highly recommend it!’ Guy Verhofstadt tweeted on May 29, 2013. The leader of the ALDE group in the European Parliament’s praise ensured the young artist plenty of media attention. In Bellinck’s exhibition Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo visitors are taken over half a century into the future. There, from the perspective of the year 2063, they look back at the beginning of the 21st century. By consecutively depicting the rise, climax and fall of the European Union the exhibition offers a disturbing retrospective on today’s Europe. The exhibition was first set up in an empty building in Brussels’ European Quarter, at a stone’s throw from where the ‘real’ House of European History – a large museum of the history of the European Union – will soon open its doors. Bellinck made his own sassy interpretation of this theoretical exercise.

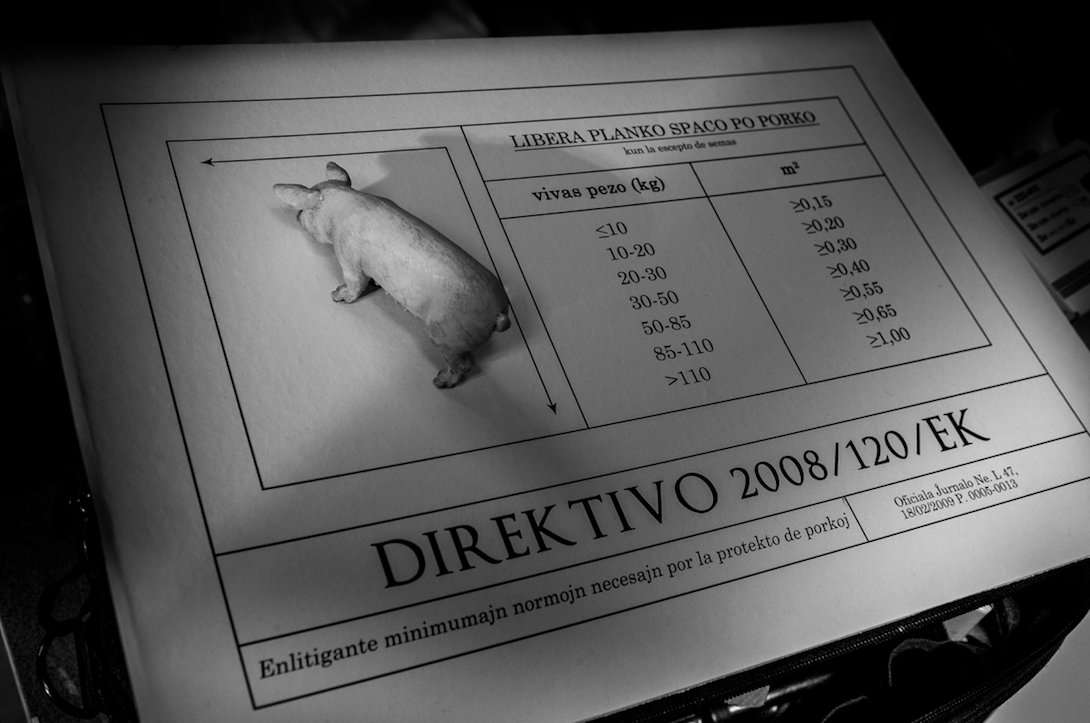

Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo (‘House of European History in Exile’) is a bureaucratic maze. Its form is reminiscent of an old fashioned memorial museum. Visitors wander along dated display cases with dusty dolls, old maps, scale models and gadgets, such as a yellowed charter of the Nobel Peace Prize and framed guidelines on the minimum length of bananas, tomatoes and leeks. In Esperanto, English, French and Dutch visitors can read how the EU period of ‘Long Peace’ was dominated by corruption, commercial lobbying and self-interest. In spite of considerable efforts by European politicians to keep the Union together through trade agreements, legislation and guidelines – which had to be translated into thirty different languages – it started to show cracks, and in Bellincks ‘museum of the future’ the union eventually explodes somewhere in the 2060s. The museum is founded by the ‘Friends of a Re-united Europe’ as a memorial to this utopian European project.

Dancer Chantal Loial in *De Waarheidscommissie*, a performance of Action Zoo Humain (2013). © Kurt Van der Elst

The ‘international exhibition about life in the former European Union’ has since travelled to Rotterdam, Vienna and Athens and currently can be seen in Wiesbaden. Bellinck’s museum was much acclaimed by the international press. ‘An intelligent plea against rising nationalism and Euroscepticism without lapsing into Europropaganda’ Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant wrote. ‘[A] clever attempt to document the EU’s current woes by constructing a fake museum of the future to examine what went wrong’ said The Guardian. In his exhibition Bellinck shows Europe’s current transition by tracing the history of its origins. He starts in the past, travels to the present and ends with a scenario for the future that might not be that far removed from the truth. He reminds us of old ideals, but also shows how these ideals have grown into grotesque realities with sometimes devastating effects, such as our European consumer behaviour. He also offers a critical take on the inhumanity of the current European migration policy. The exhibition is therefore not pure propaganda. Bellinck most cleverly shows how Europe finds itself at a turning point at the moment. Visitors are to draw a number of conclusions for themselves. In spite of the outright criticism on current European policy the exhibition also shows a strong urge to defend it. Are we willing to fight for a united Europe or will we let it disintegrate?

This is not Bellinck’s first exhibition. The main theme in his young body of work is the use of historical sources. These sources are placed in a fictional framework and highlighted. The performance Lethal inc. (2011) for instance focused on the history of methods of execution, whereas his Memento Park examines the First World War commemoration industry. In all his projects Bellinck exposes how the past is connected to the future. Content determines form here: theatre, film or exhibition. For Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo he chose a fictional museum, which offers visitors a futuristic perspective on a current reality.

Thomas Bellinck during the preparation of his exhibition *Domo de Europa Historio en Ekzilo* (2013). © Danny Willems

Guidelines in Esperanto with setting minimum standards for the protection of pigs. *Domo de Europa Historio en Ekzilo* (2013). © Danny Willems

Bellinck’s work can be regarded as part of a wider trend among young Belgian artists who explicitly engage in a dialogue between reality and fiction, between past, present and future. Elly van Eeghem and the brothers Chokri and Zouzou Ben Chikha in their projects also engage in an explicit relationship with historical, social and political realities. However, we could also add artists like Benjamin Verdonck, Jozef Wouters and Simon Allemeersch to that list, to name but a few. They often leave the confines of existing art institutes to set up shop in public spaces or other social contexts. Elly van Eeghem, for instance, is fascinated by urban development. She draws parallels between quarters in Paris, Berlin and Montreal and those in her own hometown Ghent. Together with local residents and architects she examines existing urban plans and designs, and she works on alternative forms of urban living for the future. Chokri and Zouzou Ben Chikha took the Ghent World Fair of 1913 as their starting point. Precisely one hundred years later the Ben Chikha brothers established a Truth Commission to indict the impact of our colonial past on the present. The experiment will be repeated in Antwerp soon. This time the Truth Commission will convene in the old Palace of Justice: www.actionzoohumain.be.

The street has always been a popular field of action and subject for artists. In the 1960s Guy Debord and his Situationist International already wanted to critically question existing social conditions. Debord’s agenda was explicitly political. The same goes for Brazilian theatre practitioner Augusto Boal’s the Invisible Theatre in the 1970s.

In spite of the diversity of projects these artists have some common ground. They all create a tension between fiction and reality in their work and dissociate themselves from standard art formats: it’s not theatre, an installation or an exhibition in the strictest sense of the words. Instead Bellinck, Van Eeghem and the Ben Chikha brothers develop artistic forms they derive from the social context in which they take up residence: the model of the museum, the model of the urban development project, the model of the courthouse. Since this historical, social and political reality as original source material lies at the foundation of these projects, they have decidedly documentary characteristics. And yet it’s not documentary art. These artists translate the archival sources, oral testimonies or historical plans they use into an artistic context. They put their historical sources in a fictional framework and thereby intentionally obscure the demarcation lines between fiction and reality. This translation has a distinctly critical potential, but doesn’t aim at an objective truth, nor a historically correct representation of the past. What the makers do do, is inspire different depictions of the reality in which they take up residence.

City of the future

It’s significant that this group of young artists choose the city – and by extension the public space – as their workplace. They try to find a place where they, while interacting with their surroundings, can question and put into practice such concepts as urbanity, public spaces and activism. The focal point in their work is the question how they can think about the world they want to live in. With their artistic practice they try to anchor themselves explicitly in society. In that sense working in public spaces makes perfect sense. Not because they want to escape from the institutional borders of the established institutes, like the avant-garde artists in the 1920s and 1960s. The current generation of artists deftly uses the product and content frameworks they are offered. Often social criticism frameworks are in part co-developed by the big subsidized cultural institutions.

Elly van Eeghem, for instance, is one of five so-called City residents who have been supported by Arts Centre Vooruit in Ghent since August 2012. By engaging a group of young artists with different artistic backgrounds in a dialogue in public spaces the City Residents want to develop a joint discourse around art and society. In that context Van Eeghem explores depictions of urban planning in her long running project (DIS)PLACED INTERVENTIONS. She focuses on places in Belgium as well as abroad which are going through a radical physical or social change and translates her insights into new urban and social models. She studies their history and talks to the local residents. Using these different sources the young artist makes a performance, film, installation or exhibition in which she always makes a connection to the present.

Elly Van Eeghem's showing of Siedlung (2014) in the Ghent garden district Malen, an audiovisual performance on the Berlin Hufeisensiedlung ('Horseshoe Estate') developed by architect and urban planner Bruno Taut. © Matthias Boudry

Recently Van Eeghem worked in the Ghent district of Malem. Together with a group of residents she developed alternative forms of housing for this quarter, which is under threat because of rising water levels. Van Eeghem combines a very real threat to the island (wetness) with a fictional worst case scenario (the island will be flooded soon). They joined forces with a team of architects in a Laboratorium voor de Ontwikkeling van het nieuwe Wonen (Laboratory for the Development of New Urban Living), LOW for short: www.low.gent. Here the residents designed innovative forms of housing for the city of tomorrow. The residents acted as contractor and searched for potential investors in the development and execution of a first prototype. During Plan Malem (Topography of the Island State) interested parties were given a tour and were afterwards invited to support the project financially and thus be a shareholder in securing their own future. What started as a utopian laboratory for new forms of housing evolved into a very real investigation into current themes such as privatisation, urban development and the future of council housing. At the moment Van Eeghem is working on the third leg of this project in Nieuw Gent, a housing estate south of the city centre best known for its highrise flats.

These engaged projects can of course be placed in a long tradition of artistic movements which explored the boundaries between play and reality by intervening in public spaces artistically and thus explicitly strengthening the connection between art and life. The street has always been a popular field of action and subject for artists. In the 1960s Guy Debord and his Situationist International already wanted to critically question existing social conditions. Debord’s agenda was explicitly political. The same goes for Brazilian theatre practitioner Augusto Boal’s the Invisible Theatre in the 1970s. Through ‘invisible’ actions in public spaces Boal wanted to emancipate his oblivious audience. Unlike their radical predecessors Elly van Eeghem and Thomas Bellinck’s motivations are less didactical. They do not aim for a social revolution or the emancipation of the working classes, but rather want to find forms of expression which question the current system by highlighting alternative depictions. They place a social reality in a theatrical framework. At the same time they take the liberty to fictionalize this social, historical and political reality (in this case the museum, the urban develop project, the courthouse). In this way the artists mock social frameworks and play games with the expectations of the spectator.

Courthouse of the past

With a third example I would like to show that these artists’ practices can have a direct impact on reality and the history they relate to. On April 10, 2013, in a striking video message, the mayor of Ghent Daniel Termont offered his apologies for humiliating the people of Senegal and the Philippines at the 1903 World Fair. No fewer than 128 Senegalese and 60 Filipinos were exhibited as an exotic curiosum in recreated African villages in Ghent. The Senegalese and Filipinos were part of a travelling circus for the entertainment of the white Westerner. After the fair finished these people wandered around the streets of Ghent for a month. They received 10 Belgian francs for their services, about a third of a working monthly wage back then. The illustrious writer Cyriel Buysse described them at the time as ‘the result of crossbreeding monkeys with Mongols.’

Entr’acte during the break of *De Waarheidscommissie*, a performance of Action Zoo Humain (2013). © Kurt Van der Elst

The cause of the mayor’s apology to the descendants of the victims was the Truth Commission. This Truth Commission was founded exactly 100 years after the fact by Action Zoo Humaine, the theatre company led by Chokri and Zouzou Ben Chikha. The commission explored the effect of this colonial past on the present. In cooperation with the descendants of Madi Diali, a Senegalese who didn’t survive the ‘human zoo’, the company examined what had happened exactly by recreating the facts in court in the presence of a commission of experts. The commission’s activities could be followed in the old palace of justice in Ghent. In this way the project took the shape of a legal session chaired by former governor Herman Balthazar.

The murky relationship between reality and the staging of the project was analyzed very clearly by playwright Ivo Kuyl. He emphasized the ‘realistic effect’ of the setting (the courthouse) and the fact that ‘real politicians’, ‘real Senegalese people’ and ‘real experts’ take part. Great pains were taken to make the spectator forget this was fiction, says Kuyl. At the same time the spectator is constantly reminded everything is staged. First by the Ben Chikha brothers, who act as court security officers. Next by actor Mourade Zeguendi, who protests indignantly from the audience about the fact that the audience is entertained during the intermission by a spectacular dance group of Senegalese dancers. Actress Marijke Pinoy in turn criticizes the choice to have African dancer Chantal Loial dance behind a glass wall; once more she is exhibited in a colonial perspective.

Multiple perspectives on reality

With these artistic interventions Action Zoo Humaine cleverly encourages reflection on the way in which reality shows itself to us in and by its staging. The spectator is constantly confronted with different perspectives on the situation and is actively challenged during that game. For just as in Elly van Eeghem and Thomas Bellinck’s projects, the line between reality and fiction, between reality and staging, is very fine. The Ben Chikha brothers even deliberately try to blur this line and make the resulting confusion the subject of their project. The playing with stereotypes and constant undermining of the spectators expectations provide a multiple perspective on the colonial past and its effect on the present. The result is not so much a moralizing political condemnation but rather exposes the complexity of the post-colonial debate.

Elly van Eeghem, Thomas Bellinck and the Ben Chikha brothers focus explicitly on the impact of the past on the social and political truths of today. They are not striving for an objective reality, they want to expose a forgotten history, a place or a community. They don’t claim any truth, probability or answer, but depict reality in different ways. These artists translate snippets of memories, moments of the collective past, but also new possibilities for the future to an artistic universe. In this way they offer different, multiple perspectives on reality. Mixed with depictions of reality they feed a multi-facetted reflection on the past. At the same time their interventions stimulate a critical relation to the present and open up alternative possibilities for the future.

+++

Nele Wynants

Winner Prize for Young Dutch Art Criticism 2016, second prize category Essay

This text is a copy of the article that is on the website of the International Association of Art Critics. It's an abridged version of an article published in March 2016 in FORUM+ voor Onderzoek en Kunsten (FORUM+ for Research and Arts).