This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 29 no. 1, pp. 12-20

Dialogue with Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei

Date: July 22, 2021 and October 22, 2021

ENSEMBLE: An Architecture of the Inbetween is the book by architect and artist Shervin/Sheikh Rezaei published at the end of 2020. It is the result of her first solo trip to her home country Iran, which she undertook in the winter of 2018. Sheikh Rezaei writes about the two cultures between which she moves, the Middle Eastern (Iranian) and the Western (Belgian), and the in-between feeling she experienced during her trip. In her research, she searched for a polyphonic place, an architectural ensemble that unites both cultures. She does this in two languages: Farsi and English. In a conversation with Ine Engels, she discusses the creation of this bilingual publication.

Dialoog met Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei

Data: 22 juli 2021 and 22 oktober 2021

ENSEMBLE: An Architecture of the Inbetween is het boek van architecte en kunstenares Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei dat eind 2020 verscheen. Het is het resultaat van haar eerste soloreis naar haar thuisland Iran, die ze in de winter van 2018 ondernam. Sheikh Rezaei schrijft over de twee culturen waartussen ze zich beweegt, de Midden-Oosterse (Iraanse) en de westerse (Belgische), en het in-between-gevoel waarmee ze werd geconfronteerd tijdens haar reis. In haar onderzoek zocht ze naar een polyfone plek, een architecturaal ensemble dat beide culturen samenbrengt. Ze doet dit in twee talen: het Farsi en het Engels. In een gesprek met Ine Engels geeft ze toelichting bij het ontstaan van deze tweetalige publicatie.

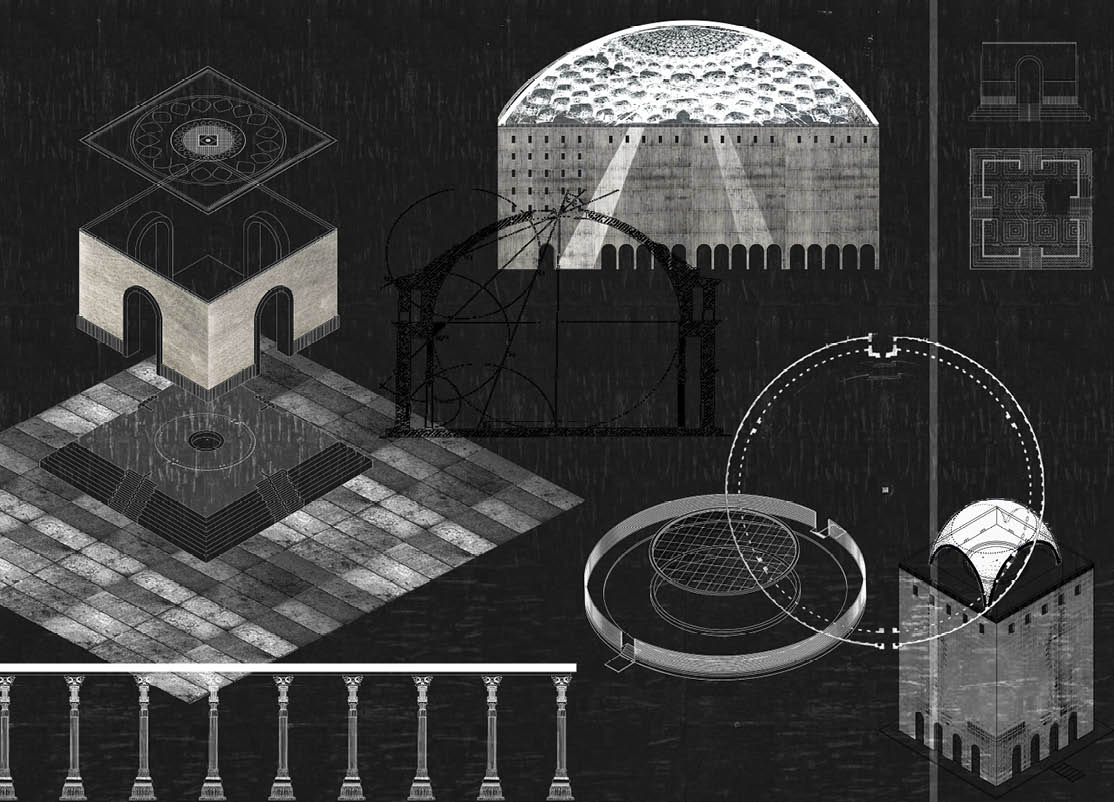

Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei designed an architectural ensemble based on Foucault’s theory of heterotopia.1 She created an intermediate space where different places, cultures, and identities that seem incompatible at first glance are united. As a transcultural person, Sheikh Rezaei believes in providing a transparent framework for anyone who wants to tell her/his/their personal story without prejudice. The ensemble, which consists of an entrance as a symbol of birth, a temple as a symbol of the future, and a mausoleum as a symbol of the past, forms this transparent framework. It is a carte blanche and at the same time an illusion of neutrality. A space constantly welcoming new stories is never neutral, but inherently subjective in nature.

Fig 1: PLAN ENSEMBLE

Ine Engels:

ENSEMBLE turned out to be a very personal story. How did the book come about?

Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei:

ENSEMBLE began with my master’s thesis. I had to make a trip so I chose to travel to Iran in 2018, the country where both my parents were born and to which I feel closely connected. During my trip, I kept a diary with photos of the Iranian landscape. I briefly described my experiences and my state of mind. The transition from diary to thesis and, later, ENSEMBLE consisted of seeking common ground with others. A work of art only becomes interesting when others can identify with it and express themselves in it. Collaboration is very important to me. After I completed the diary, I spent time designing, theorizing, writing, and choosing materials. Artist Weronika Zalewska, who wrote the prologue, played a huge role in finishing the book. She translated my text into a visual language. Thanks to her, the book is written in such a lyrical way.

IE: ENSEMBLE is written in English and Farsi. Why did you choose these languages?

I considered English an in-between language, Farsi my mother tongue and Dutch the language I use on a daily basis.

SSR: The first version of the book was written in Dutch, Farsi, and English. I considered English an in-between language, Farsi my mother tongue and Dutch the language I use on a daily basis. For various reasons, we decided not to publish in Dutch. This was mainly the publisher's choice. It was important for me to keep Farsi and English present in the book as I talk about my two identities, which are shaped by the languages I speak. I believe that our identity is shaped by the language we possess. When we express what we see or hear, we rely upon language to communicate. Therefore, language is always important, not only in ENSEMBLE, but in all works that express something.

IE: Do you regret that the Dutch language has been left out of the final publication?

SSR: On the one hand, I do regret it because Dutch is the language that I have the most affinity with. On the other hand, I understand the choice. Publishing in Dutch does not necessarily address an international readership. Most readers read texts in English without difficulty, so Dutch would not have added any value to ENSEMBLE. Moreover, using two languages instead of three visualizes my concept of the in-between. I write about moving between the Middle East and the West, two cultures expressed in two languages: Farsi and English. And yet, I must admit that I would perhaps do things differently now. Moving between cultures is such a rich experience, involving different languages and language forms. If ENSEMBLE were to be published now, I would try to keep the Dutch in it.

Fig. 2: Analysis drawings - ENSEMBLE, 2018

IE: You consider English an in-between language and Farsi your mother tongue. Do you feel closer to one language than the other?

SSR: I chose to publish in Farsi mainly because of my parents and family. I wanted them to understand what I was talking about in my book. That is why I asked my cousin, Hanieh Rezvani, to translate the text into Farsi. Niloufar Nematollahi and Ehsan Yadollahi reviewed the translation. My knowledge of Farsi is rather basic. I use the language mainly in a domestic context, so translating a theoretical text is no easy task. Because of this language barrier, it is often difficult to explain my work in detail to my parents. Before ENSEMBLE came out, they knew my work primarily through images. I was delighted to finally show them a theoretical text in Farsi and share my work with words. Translating my work into Farsi was also an opportunity to prove myself. I grew up believing that I had to work hard in order to get somewhere. Ambition has always been encouraged in my home. I understand my parents in that respect. They moved to Belgium for the future of their children, so it is important to make something of that future. I consider English an in-between language because it is a universal language. When we meet people who speak another language and there is a language barrier, we search for words in English. In this sense, we use English to compensate for our lack of knowledge.

IE: You titled your book ‘An’ Architecture of the Inbetween and not ‘The’ Architecture of the Inbetween. Why?

SSR: I wrote ENSEMBLE in eight months. After that, I could not look at my work for a while. Once a text is finished, I get the impression that its content still needs to be accurate in a few years’ time. Then, it seems as if I consider my theory to be the absolute truth, which is certainly not the case. Hence, I chose to create ‘a’ possible architecture and not ‘the’ architecture.

IE: In addition to your own voice, you welcome other voices in ENSEMBLE. Four transcultural women artists and thinkers: Mira de Boose, Deveny Faruque, Niloufar Nematollahi and Oriana Lemmens share their story in the epilogue. Why did you decide to add an epilogue to the book?

SSR: I wrote the epilogue because I realized at the end of my research that I was mainly referring to white Western male authors and artists. This bothered me. I had two options. I could either search for Iranian female artists, with whom I feel a connection and to whom I could refer. Or I could write an epilogue in which I am honest about the shortcomings of my research and in which I ask other transcultural women to speak about their work and background. I believe it is important for women from diverse backgrounds to have a platform to be heard, and not just seen. Today, diversity is increasingly represented in society, but the voices often remain unheard. Listening to the personal stories of others also helps us to break free from stereotypes and standardizations. In ENSEMBLE, I aim to create a new multifaceted image by uniting different perspectives.

IE: In your references, you mention Robert Smithson, Donald Judd, Dan Graham and Robert Morris. Why the interest in land art2 and minimal art?3

Fig. 3: Plexiglass model I - ENSEMBLE, 2018.

Photograph: Tiny Geeroms

Fig. 4: Plexiglass model II - ENSEMBLE, 2018.

Photograph: Tiny Geeroms

SSR: I have always felt a connection with the minimal artists and conceptual artists. They strip their work of ornament until they get to the concept, the pure essence. Just like the minimal artists, I look for peace in my work, partly because I have a very open and lively personality. I have not always been able to express myself fully. Many women will recognize themselves in this. Too often, we women temper our voices to conform to society's expectations. bell hooks talks about ‘sexist socialization’ in one of her works, addressing that women are systematically taught that assertiveness is an exclusively male trait.4 Women, especially women of colour who stand up for themselves are stereotypically labelled as loud or excessive. I often discussed this with friends and family. My father, who only wanted to protect me from these prejudices, urged me to stay in line with societal norms. For instance, I replaced my patterned clothes for a more neutral look so I would not stand out too much. Sometimes I still feel like I am too much of an extrovert. It depends on the people around me. I have several friends from the field of performance with whom I can be myself without worrying about prejudice. My work is a meditative practice that allows me to unwind. I don’t have to scream to express myself in my work. The desire to express myself fully is reflected in my ensemble designs through the use of plexiglass. It is a transparent material that, like a chameleon, adapts to the colour and light conditions of its surroundings. Creating a space where everyone can project her/his/their story without having to comply with societal norms and standards is a very attractive and at the same time utopian image.

IE: Could it be that you (un)consciously opted for these Western references to meet the demands of the market in which your book was published?

SSR: The selection of references is a consequence of my Western education. I went to school in Belgium my whole life and studied for six months at the Bauhaus University in Weimar. I admire the modernist style, especially the work by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. I also spent a long time working with the functionalist idea ‘form follows function’. Just like in minimalism, the focus lies on the pure essence. It is important for me that these sources of inspiration, which have shaped my Western identity, are (in)directly represented in my book. On the other hand, I am not afraid to include patterns and ornament in my designs in ENSEMBLE. The aim of the book was to search for the in-between state between the West and the Middle East and, thus, to express both cultures/identities. That is why I chose to execute my ensemble designs in different materials. Plexiglass, a popular medium for the minimalists, is an expression for the West. Carpet, a material that is omnipresent in Iran, represents the Middle East. The carpets were made by a local company in Belgium. In the future, I would like to have them made in Iran. That way, you would see the difference between machine work from the West and craftmanship from the Middle East.

My aim was to find an architecture that would be recognizable for different people, regardless of their background, culture and beliefs. A transcultural architecture that transcends differences and connects people. This is a utopian vision, one that is consequently unattainable.

IE: In the epilogue, Niloufar Nematollahi addresses the dangers of fetishism and cultural appropriation.5 What is your opinion about this?

SSR: At first, I found it confronting to read Niloufar’s text. I needed some time to reflect on what she had to say. Today, I am very grateful for her input. Niloufar made and still makes me look differently at my work. My design is a mixture of Western and Middle Eastern architecture. I literally combined the plans of well-known buildings such as the Propylaea of the Acropolis in Greece, the Arch of Titus in Italy, Palladio's Villa La Rotonda and references to squares such as Isfahan in Iran, and made a heterotopia out of it – a combination of different architectural elements. My aim was to find an architecture that would be recognizable for different people, regardless of their background, culture, and beliefs. A transcultural architecture that transcends differences and connects people. This is a utopian vision, one that is consequently unattainable. Trying to eradicate racism is a good comparison. It is simply not possible, but we can always keep striving for it. For me, the difference with fetishism and cultural appropriation depends on the context. Do you strive for a better understanding of cultures or do you appropriate a culture to stand out or gain recognition? For example, I find it difficult to hear Belgian youngsters mix Arabic terms with Dutch. Although it is nice to see languages evolve, it is always important to respect the original context.

IE: This reminds me of the current debate on diversity. Do you think this is a conversation that is being held out of genuine concern or mainly because diversity is a trendy topic in today’s society?

SSR: Certain sectors are going through a transitional period. The conversation about diversity is happening because people realize that the time has come to listen to voices of colour. I don’t think people are genuinely ‘concerned’ or want to be ‘trendy’ when it comes to diversity. Today, questions are being put on the table that people did not dare to ask in the past. Diversity has become a part of our contemporary reality. To keep this conversation going, we need to take targeted action. Growing awareness is not enough. When I was teaching at LUCA School of Arts (Ghent), I asked my students to find twenty references of which at least half referred to female authors and at least half to non-Western authors. That is really not an easy task. I also often look at art made by men without thinking twice about it. It happens unconsciously. This is partly due to our education system, which teaches students a very one-sided perspective. Nevertheless, I do notice that our education system is evolving. This year, I am following the course ‘Kunstenaarsteksten’ at KASK & Conservatorium (Ghent) and I am pleasantly surprised by the wide variety of authors who are being discussed. Non-Western authors are no longer singled out because of their origin, but are simply part of the course. Although this is a huge step forward, the search for other voices of colour remains something that must be actively pursued.

Fig. 5: Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei with mirror of the ENSEMBLE, 2021.

Photograph: Emma Raymaekers

Fig. 6: Tapestry of the ENSEMBLE II, 2021.

Photograph: Tiny Geeroms

IE: In the prologue, Weronika Zalewska talks about the artistic practice of the architect who takes on the role of artist in addition to the role of maker when working with stories. How would you describe your own artistic practice in ENSEMBLE?

SSR: I call myself an architect because I graduated as one and obtained an official title. For me, however, an architect is the total package of artist, illustrator, painter, sculptor, designer, mathematician, and builder. When I have mastered everything, I will really consider myself an architect. Perhaps this total package is a utopia in itself. Can you ever master everything perfectly? The same applies to the role of artist. I don't like to call myself an artist because, firstly, I haven’t been educated as one, and secondly, I don’t feel like I have been in the art world for long enough. It is surprising that I present myself as an artist to architects and as an architect to artists, as if I could never be part of both worlds. There is a lot of uncertainty involved when naming myself an architect and/or artist. It is difficult to draw the imaginary line between the two. I did go through an exceptional process. At school, I had lessons from Explorative Architecture & Design (EAD) teachers who taught me to design conceptually. Then I started working part-time at an architectural firm, where I often took care of artistic projects. I have always been closer to the artistic practice than the building practice. Recently, I stopped working in architecture to focus on my own art practice. Nevertheless, I am trying to embrace both roles.

IE: Architecture was originally an exclusively male profession. Do you think this makes it hard for you to call yourself an architect?

SSR: In my case, it is no so much the profession, but the style of my work that is often associated with ‘the masculine’. The influences of modernism and minimalism result in a sober style without rich colours or ornament. I notice that this style is often linked to a certain severity and authority, two concepts that in turn are stereotypically attributed to men. Because I am an assertive female architect/artist working in this ‘strict’ style, I sometimes get labelled as ‘loud’ or ‘dominant’. This is an example of gendered language that is neither beneficial to men nor women. In ENSEMBLE, I aim to create a space where we learn to listen to a person’s story without categorizing them on the basis of stereotypes.

IE: How do you see the relationship between language, culture, and identity?

SSR: These three concepts form part of the same ensemble. They need each other to express themselves. Language allows for the construction of an identity within a culture. Culture must be translated into language to construct an identity. And identity can only be shaped within a culture through the use of language.

In ENSEMBLE, I tried to bring my Iranian identity closer to my Belgian identity to reduce the distance between the two. The question of whether I have succeeded in doing this is less important to me. My work has been published, but I am far from done. Just like moving between cultures, I am also floating between positions. As a transcultural female artist, do I fully support the use of Western references in my work? I cannot give a definitive answer. I often end up with mixed feelings. At those moments, I remind myself of the essence of ENSEMBLE, which is not about representing two separate cultures, but about enabling contact between the two, creating a third space without hierarchy. This is a very idealistic image that can never be fully realized. The most important step for me has been becoming aware that the process of uniting cultures, and not the result, is what really matters.

Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei. ENSEMBLE: An Architecture of the Inbetween. Art Paper Editions, Ghent, 2020.

From 19 March 2022 until 30 April 2022, the exhibition Archive, images: vergetelheid / əˈblivēən by Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei is on show at Valerie Traan Gallery, Antwerp.

+++

Ine Engels

is a student of Art History, Musicology, and Theatre Studies at Ghent University. In 2019, she obtained a master’s degree in Linguistics and Literature: English – Spanish at the same university. During the academic year 2020-2021, she did an internship at FORUM+.

Shervin/e Sheikh Rezaei

is a Belgian architect and artist based in Ghent (°1994, Belgium/Iran). She studied Medien Architektur at the Bauhaus University in Weimar and graduated in 2018 as an architect in Experimental Architectural Design at the Faculty of Architecture of KU Leuven in Ghent. Afterwards, she worked as an architect at Jan De Vylder Inge Vinck Architects and was appointed for one year as a guest lecturer of Mixed Media for Interior Design at LUCA School of Arts in Brussels and Ghent. Currently, she is focusing on her own art practice.

Footnotes

- Heterotopia: mixing different architectural elements as a means of relating. Heterotopia is capable of placing multiple spaces next to each other, or even within each other, in one place; multiple sites that might seem contextually incompatible. It is a space where objects, spaces, feelings, stories, juxtapositions are made possible beyond the logic of our cultural perception. Term derived from Foucault, Michel. "Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias", in Architecture / Movement / Continuité, 1967. Translated from French by Jay Miskowiec. ↩

- “Land Art or earth art is art that is made directly in the landscape, sculpting the land itself into earthworks or making structures in the landscape using natural materials such as rocks or twigs.” Tate Art Terms, www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/l/land-art, last consulted on 22 October 2021. ↩

- “Minimalism is an extreme form of abstract art developed in the USA in the 1960s and typified by artworks composed of simple geometric shapes based on the square and the rectangle.” Tate Art Terms, www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/m/minimalism, last consulted on 22 October 2021. ↩

- hooks, bell. All About Love: New Visions. HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 2000. ↩

- The full text by Niloufar Nematollahi can be found on www.shervinsheikhrezaei.com. ↩