This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 32 no. 2, pp. 58-65

Creativity and collaboration in fashion education. Languages, skills, and methodologies in a collaborative learning approach

Andrea Cammarosano

Creativity in fashion is not only about individual talent or personal vision – it is also about how people share ideas, combine skills, and work together to create something new. Yet in most fashion schools, the emphasis remains on personal expression and individual creativity, while the role of teamwork and collaboration – not only as a practical necessity but as a vital source of idea generation – is too often overlooked.

Over the past five years, my PhD research1 has examined the dynamics that take place when ideas, materials, techniques, and working methods circulate among diverse people and ecosystems: designers and technicians, ideators and makers, students and teachers. This research culminated in my publication CLU++ER: Creativity + Collaboration in Fashion Education, which expands the PhD study into a broader test of educational and creative approaches.2 The images presented in this article are drawn from that publication.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Figures 1 and 2: Reiteration of the PhD empirical research, Milan and Como, Italy.

In this activity, participants co-developed garment shapes, cuts, and screen printing designs in collaboration with factory specialists, improvising and adapting with available resources. Fig. 1 shows one of the outputs: a neoprene top draped, crafted, and printed by Léo Emmanuelli, Antonia Sell, and Rémy Boutareau in collaboration with Stamperia di Lipomo, Como. Fabric supplied by Gruppocinque. Life-scan visualization of the garment developed by Sublitex. Fig. 2 shows a detail from the artistic publication CLU++ER: Creativity + Collaboration in Fashion Education. Layout by Andrea Cammarosano and Margherita Maria Chiara Munafò. Book production by Bruno De Vos.

The circulation of ideas and information between the different players involved in the creative act relies on a particular kind of vehicle, which I call Creative Languages. These serve as a medium of communication for creative processes: their defining feature is a direct, tangible link to the subject matter. Textile swatches, sketches, and spec sheets are examples of Creative Languages. Their attributes – physical and visual, not only verbal – make them a powerful means of capturing how ideas arise and evolve across specific environments, from studio to factory, from classroom to professional settings.

By focusing on Creative Languages, researchers can observe how responses either remain rooted in domain-specific tasks – like textile development – or expand toward broader, cross-disciplinary, or domain-general solutions – like an overarching aesthetic narrative. In fashion design, for example, a textile choice must integrate seamlessly with the cut, construction, and finishing details of a garment, eventually culminating in an overarching story for a whole collection. These “languages” therefore track how creativity moves from specialized concerns to more expansive conceptual frameworks. When a designer and a textile maker collaborate, they bring different ways of thinking – one focused on shape and garment fit, the other on fabric surface or texture. When these approaches meet, new and unexpected ideas emerge that neither could have discovered alone. This back-and-forth process not only shapes the final product but also transforms the creative habits and identities of the people involved. The goal of my research was to develop an educational approach that integrates structured skill-building activities with openness, communication, and the capacity to co-create, fostering both technical proficiency and collaborative creativity.

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Figures 3 and 4: The Studio Project, HEAD – Genève, October–November 2024.

Garment and reflections by Hippolyte Laporte and Isabela Bueno, reinterpreting archival references through the material qualities of an organza fabric developed by Gruppocinque, Como. Throughout the activity, participants were also asked to keep diaries and observations on their individual experiences and their collaborative process. Fig. 3: Photo Alessandro Di Palma; Styling Leonardo Persico; Make-Up and Hair Cinzia Trifiletti; Talent Dasha Lalic at Di Next Management; Post Production Gloria Torquati. Shot at Illuminotecnica Media Lab, NABA, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti, Milan.

To advance this goal and critically examine these processes, I systematically drew upon and integrated insights from established theoretical models of creativity, using them to frame, interpret, and guide the design of workshops and collaborative activities within the research. At the individual level, I drew on Teresa Amabile’s work, which highlights how personal expertise, creative thinking skills, and intrinsic motivation influence one’s ability to generate new ideas.3 At the group level, the dynamics described by Woodman, Sawyer, and Griffin reveal how collaboration requires shared understanding, negotiation, and mutual adjustment to allow collective creativity to emerge.4 Finally, I considered the level of specific skills, using the perspective of Kaufman and Baer, who emphasize that creativity does not manifest equally across all domains; rather, it is shaped by the particular knowledge and techniques relevant to each field.5

This integrated framework suggests that collaborative creativity is inherently multidimensional: what counts as creative at the individual level (such as a personal design insight) may not align with what is creative at the group level (such as a successfully negotiated joint solution), or at the level of domain-specific skills (such as mastery of a particular garment construction technique). For this reason, collaborative creativity must be evaluated differently depending on whether we focus on individual contributions, group processes, or the quality of the technical execution and material outcome.6

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

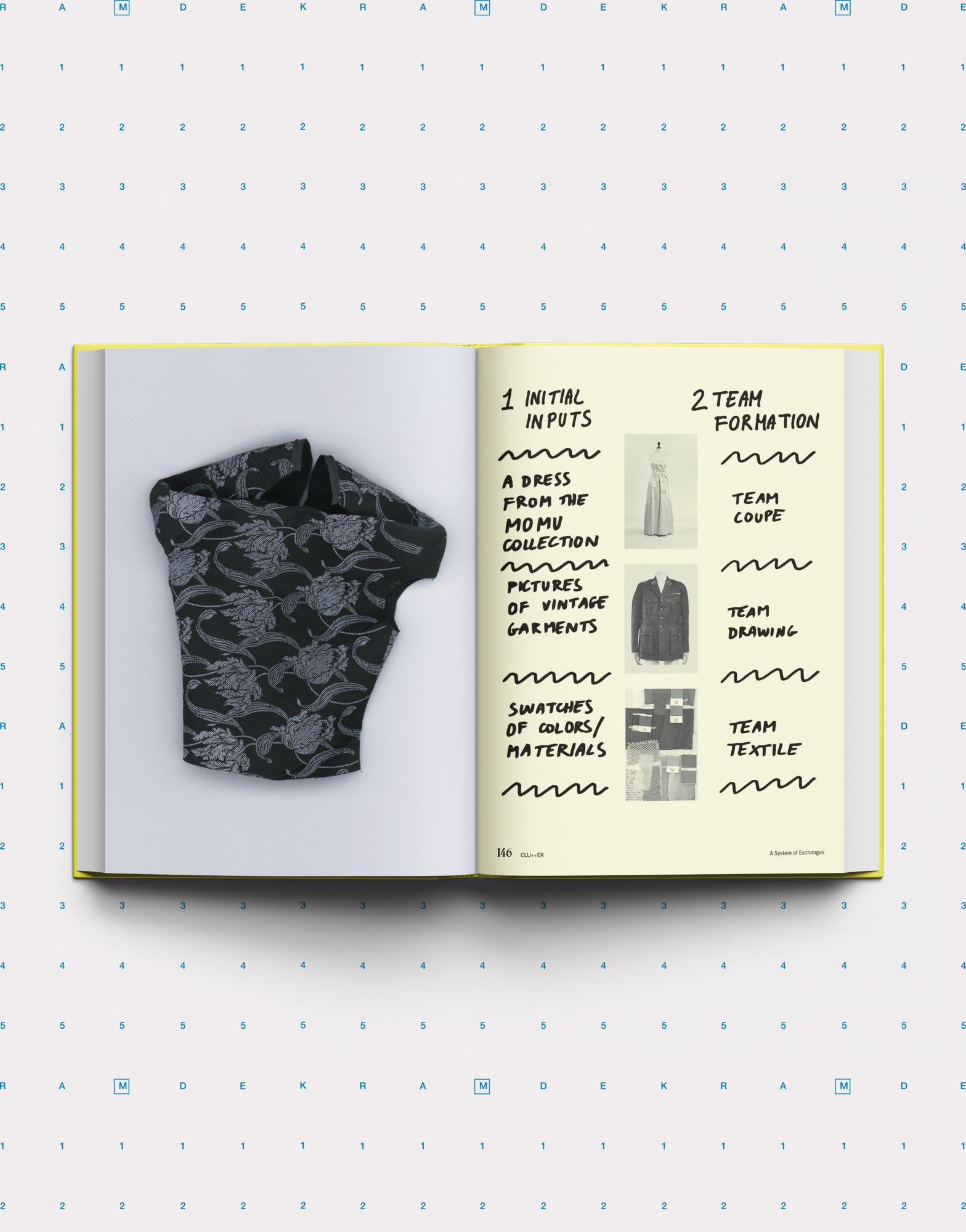

Figures 5 and 6: Process and reflections from the Studio Project, Antwerp, February 2022 (PhD empirical research).

In-depth one-on-one interviews complemented the observation of the collaborative process, enriching the researcher’s notes with participants’ perspectives on particularly meaningful moments or behaviours that either supported or inhibited creative development. Fig. 6 shows a detail from the CLU++ER publication, featuring a dress chosen as one of the inputs for Group 2 (Alexandre Warunek, Jaden Li, Berenike Gregoor, Babett Byrtus, and Guillaume Gossen). Dress by Christian Dior from the Study Collection MoMu Modemuseum Antwerpen. Photo Stany Dederen.

Importantly, these theoretical reflections were not only abstract models but also directly informed my experiments in fashion making. Drawing on practice-based research, I connected this framework to the core processes of garment design and construction. Influenced by scholars such as Rickard Lindqvist7 – who advocates for an open and dynamic approach to garment construction – and by my previous investigations into the interplay between graphic embellishment and pattern cutting, I designed a series of activities that embodied these principles in action.

These activities were initially structured as workshops focused on specific skill areas, such as pattern-making, garment construction, and collection development. Over successive iterations, they evolved into a progressive learning structure, proposed as a framework for skill development and collaborative creativity throughout the length of my PhD research.8 This current article does not detail the full integrated framework – which represents the outcome of the dissertation – but focuses instead on individual workshops and activities, each with its own distinct and often surprising perspective, providing the necessary context for the images presented alongside this text.

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Figures 7 and 8: Process and outputs from the TRAME Workshop, Milan and Como, September 2024.

The dynamics of creative collaboration derived from the PhD research were applied here to a laboratory project with secondary technical high school students. Through active peer tutoring, young university students supported and coached teenage participants, fostering skill-sharing and mutual learning. Garments produced by Jana Z., Susanna Z., and Maria Angela Z. Printed at De Ca Stamp, Como. Life-scan visualization of the garments developed by Sublitex. Fabric: Astronauta by Gruppocinque. Photo Gloria Torquati.

The workshops varied in scope and disciplinary focus. Some were preparatory and multidisciplinary, involving students from fashion, printmaking, and graphic design, such as those held at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp (September 2021, 12 participants) and at NABA Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan (November 2023, 22 participants). Others were single-discipline preparatory workshops, conducted with first-year fashion students at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp (February 2022, 40 participants) and HEAD – Genève (October 2022, 24 participants). Finally, a series of workshops was conducted with secondary school students (aged 14-17) at technical institutes in Milan, in collaboration with IIS Caterina da Siena. These sessions aimed to explore how the framework and methods developed in previous workshops could be applied in a different educational context, engaging younger participants with varying levels of experience and skills.

All of these workshops shared an open structure that enabled participants to explore and exchange across different creative languages without rigidly predefined outcomes. Building on these experiences, the research was further anchored in a semi-structured empirical study, “The Studio Project,” conducted in February 2022 with 52 second-year fashion students at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp.9 The workshop was designed to systematically gather inputs and outputs, conduct participant interviews, produce photographic documentation, and collect detailed data, enabling a comprehensive visualization of process evolution at the technical, interpersonal, and artistic levels.

Fig. 9

Figure 9: Process images from the Studio Project, Antwerp, February 2022 (PhD empirical research).

Participants were divided into groups, each further subdivided into teams according to specific creative languages – Coupe, Drawing, Textile – chosen by the participants based on their individual inclinations and motivations. This structure made it possible to observe and map the emergence of creativity not only at a domain-general level but also within domain-specific contexts. [1] Polina (Coupe Team, Group 5) drew inspiration from a vintage trench coat and reconstructed it along organic curves, later established as a group guideline. [2] Léo and Antonia (Coupe Team, Group 1) update the pinboard with photos from their first mock-up fitting. [3] Gabrielle (Drawing Team, Group 3) and Sofia (Coupe Team) review inspirational material to shape their work on day two. [4] Paula (Coupe Team, Group 4) begins draping on a dress form, seeking serendipitous ideas to share during feedback sessions. Photos Andrea Cammarosano and Catherine Smet.

From this study, six participants – selected for their distinctive and diverse collaborative styles – were invited to re-enact a similar activity in February 2023, divided between my studio in Milan and a textile factory environment in northern Italy. This final phase explored how the collaborative dynamics observed in the academic setting translated into a professional production context, where factors such as industrial tools, scale, and workflow rhythms further shaped the interplay between individual creativity, group decision-making, and technical execution.

The same structure was applied to a reiteration of “The Studio Project” at HEAD – Genève (November-December 2024, 14 participants), extending the investigation of collaborative processes across different settings and contexts.

In all these activities, participants were encouraged to move freely between designing, making, and experimenting, while exchanging skills and viewpoints. In one workshop (The Studio Project, HEAD – Genève), participants explored garment construction directly on mannequins and live bodies, using contrasting materials such as stiff organza or fluid satins.10 Instead of relying on fixed patterns, they shaped and transformed fabric in real time, letting material properties and bodily movement guide the design.

Fig. 10

Figure 10: Process images from the Studio Project, Antwerp, February 2022 (PhD empirical research).

The activity was constantly observed in its evolution, from initial inputs to outputs; pictures of progress, intermediate artifacts, and pinboards used by participants to communicate tasks and ideas were collected and mapped, forming the core of the empirical PhD study material. [1] Sofia (Coupe Team, Group 3) prepares to cut fabric provided by the Textile Team, using a pattern she drafted by interpreting a sketch from the Drawing Team. [2] Jaden (Coupe Team, Group 2), inspired by the idea of boxy shapes, experiments with modular square-based pattern-making. His idea was further developed using laminated crochet squares by the Textile Team. [3] Alexander and Babette (Textile Team, Group 2) organize their colour and print concepts on the pinboard, starting from the idea of using a crochet sample as a stamp on bright orange fabric. Photos Andrea Cammarosano and Catherine Smet.

In other instances, the mix of abilities in each team – some participants skilled in dyeing and printing, others in tailoring or surface manipulation – led to unexpected outcomes. For instance, one group combined recycled fabrics with handmade prints to create bold, sculptural collars and pockets inspired by historical dress. Another experimented with subtraction cutting, producing dresses that unfolded and draped in unpredictable ways, further enhanced by prints that echoed the garments’ contours. These prints were developed through an exploratory process, mixing pigments, inks, and natural materials sourced from the surrounding environment in a serendipitous manner.11

+++

Crucially, these experiments made visible the interplay between the different dimensions of creativity identified in my theoretical model. On the individual level, students developed personal discoveries about fabric behaviour and shape. On the group level, they negotiated design decisions, solved material challenges together, and shared tacit knowledge. On the technical-skill level, they applied and expanded concrete making abilities – such as cutting, sewing, or printing – that shaped the final forms.

Collaborative creativity in fashion education is best understood as an entanglement of multiple levels – not as a single process, but as a layered set of exchanges between people, materials, skills, and ideas.

When these processes moved into professional spaces – such as a textile factory in northern Italy – the results deepened further. Participants used industrial printing machines to create large graphic motifs, then designed modular garment pieces that could be assembled into jackets or bags depending on the wearer’s mood. The factory environment broadened their sense of scale, material possibility, and production reality – again integrating technical skill, group decision-making, and personal creativity in ways that theory had anticipated, but practice made real.

This research shows that collaborative creativity in fashion education is best understood as an entanglement of multiple levels – not as a single process, but as a layered set of exchanges between people, materials, skills, and ideas. Each level – individual, group, and technical – requires distinct methods of support and evaluation, and each contributes in unique ways to the richness of the outcome. Building on these insights, the outcome of the research is a framework for fashion education that operates across two interrelated dimensions: from the individual to the group level, and from domain-specific to domain-general skills. The goal of this framework is to provide flexible tools and strategies that allow teachers, facilitators, and students themselves to navigate this spectrum, adapting their approach as the skills, abilities, and collaborative dynamics of individuals and groups evolve over time.

+++

Within this multi-level framework, the question of leadership becomes crucial. In my case, I began from a position in which I held a clear leadership role – especially in the phase when projects took place in educational and school contexts, where participants explicitly asked for guidance, and I was also developing these ideas myself. However, as the projects shifted into more hybrid contexts (for example, in extra-school settings), my role evolved towards that of a facilitator: someone who provides groups with communication and decision-making tools, and allows processes to self-organize.

Students, too, can evolve in their leadership roles – from “leaders” of their groups to “positive actors” who facilitate their team-mates’ work. This evolution relies on individual factors (which teachers can recognize and highlight), on repeated practices (groups that continue to work together over time), and on deliberate educational focus (developing different styles of creative leadership in students).

I observed how this theme played out within the working groups themselves, noting both the positive and problematic effects of “top-down” leadership, but above all the emergence of figures I would describe more as “positive actors” than as traditional leaders – people who facilitated communication and decision-making in ways very similar to the role I was gradually building for myself.

Fig. 11

Figure 11: Reiteration of the PhD empirical research, Milan and Como, Italy.

Several activities were repeated outside the school context to observe how diverse environments shape and impact collaborative styles and creative processes. Pictured: Screen archive at Stamperia di Lipomo, Como, one of the locations of the activities. Photo Alessandro Leri.

The “communication facilitator,” in this sense, should be understood in relation to the specific creative languages at play (patternmaking, draping, textiles, etc.): a mediator of exchanges between these languages, active above all in the interpersonal dimensions (organizing pinboards, fostering practical experiments, encouraging the exchange and circulation of materials and tools among diverse participants) rather than in purely artistic terms (centred on personal expression) or purely technical ones (effective for pragmatic exchanges, but less so for divergent or dialectical ones). This same principle, I believe, applies to the role of the teacher-facilitator: someone able to activate semi-structured systems of exchange between people, rather than simply “inspiring” through artistic languages or “training” through technical ones.

+++

These insights and the resulting framework for fashion education are presented in detail in the publication CLU++ER: Creativity + Collaboration in Fashion Education, providing both theoretical grounding and practical guidance for teachers, facilitators, and students.

+++

Andrea Cammarosano

is a designer, artist, and educator. A graduate of the Fashion Department of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, he worked for Walter Van Beirendonck, for his own eponymous label, and for different other brands in the fashion industry. In 2018, Cammarosano founded CLU++ER, a project for the exploration of creative methods rooted in performance, improvisation, and collaboration. In 2025, he completed his PhD in the Arts at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp and at ARIA / UAntwerp.

Footnotes

- Cammarosano, Andrea. Inter-Relational Creativity. 2024. Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, ARIA (Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts), University of Antwerp, PhD dissertation. ↩

- Cammarosano, Andrea, ed. CLU++ER: Creativity + Collaboration in Fashion Education. Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp, AP University of Applied Sciences and Arts; NABA, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti; HEAD–Genève, Haute école d’art et de design, 2024. ↩

- Amabile, Teresa M. Creativity in Context. Westview Press, 1996. ↩

- Woodman, Richard W., John E. Sawyer, and Ricky W. Griffin. “Toward a Theory of Organizational Creativity.” Academy of Management Review, vol. 18, no. 2, 1993, pp. 293-321. ↩

- Kaufman, James C., and John Baer. “The Amusement Park Theory of Creativity.” Creativity Across Domains: Faces of the Muse, ed. by James C. Kaufman and John Baer, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005, pp. 321-28. ↩

- Agars, Mark, James Kaufman, and Tiffany Locke. “Social Influence and Creativity in Organizations: A Multi-Level Lens for Theory, Research, and Practice.” Research in Multi-Level Issues, vol. 7, 2007, pp. 3-61. ↩

- Lindqvist, Rickard. Remarks on the Foundation of Pattern Cutting. 2015. University of Borås, PhD dissertation. ↩

- Cammarosano, Inter-Relational Creativity, chapter 8, p. 140. ↩

- Ibid., chapter 5, pp. 92-104. ↩

- Ibid., chapter 9, p. 171. ↩

- Ibid., chapter 9, pp. 168-69. ↩