This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 32 no. 2, pp. 4-15

Walking the unmapped. A proposal for reimagining the history of art residencies through cross-cultural methodologies

Pau Catà

This paper reimagines the dominant history of residencies by highlighting cross-cultural methodologies and artistic research as sites of knowledge-making. It explores early mediaeval Islamic approaches to creativity and travel, bringing together post-representational cartography and al-Khabar narratives. Through the case of Beyond Qafila Thania, an experimental walking residency, it advocates for plural knowledge systems, challenges dominant epistemologies, and proposes a more inclusive historiography grounded in situated, hybrid methodologies.

Dit artikel herinterpreteert de dominante geschiedenis van residenties door crossculturele methodologieën en artistiek onderzoek te benadrukken als terreinen waar kennis wordt gecreëerd. Het onderzoekt vroegmiddeleeuwse islamitische benaderingen van creativiteit en reizen, waarbij post-representationele cartografie en al-Khabar-narratieven worden samengebracht. Via het voorbeeld van het experimentele wandelresidentieprogramma Beyond Qafila Thania pleit het voor pluriforme kennissystemen, daagt het dominante epistemologieën uit en stelt het een meer inclusieve historiografie voor die gebaseerd is op gesitueerde, hybride methodologieën.

Flawed assumptions: A critical perspective on the history of art residencies

Since the 1990s, art residencies – defined as temporary living and working environments for artists and researchers operating outside their usual environments – have expanded exponentially on a global scale. This rapid proliferation has prompted a need for self-reflection within the field, as evidenced by the publication of multiple monographs such as Re-tooling Residencies; ON-AiR; Mapping Residencies; Unpacking Residencies; Bringing Worlds Together; On Care; and Residencies Reflected.1 The significant number of publications attests to the widespread interest, shared by practitioners and researchers alike, in reflecting on art residencies’ assets, their contemporary challenges and, most importantly, their future perspectives. Yet, amidst these timely discussions, an important area of inquiry remains notably under-researched: their history.

The limited existing literature on the history of art residencies – comprising brief essays and introductory accounts – commonly traces their origins to the burgeoning artistic patronage and the establishment of art colonies in northern Europe during the late nineteenth century. This narrative is replicated in the website of Transartists, the leading international network of art residencies, and in the 2016 EU Policy Handbook on Artists’ Residencies, which respectively dedicate only a few paragraphs and a single page to this topic.2 In one of the most significant publications on art residencies to date, Contemporary Artist Residencies: Reclaiming Time and Space, leading researchers Taru Elfving and Irmeli Kokko highlight this critical gap, noting that “there is no consistent report available on the background and history of art residencies.”3 Indeed, apart from more recent efforts such as Kokko’s proposal in Bringing Worlds Together, the lack of a coherent body of work in this field demonstrates that the genealogical co-relation between artistic practice and the journey has not yet been approached from a critical perspective.4 Moreover, I argue that this discourse rests on at least two flawed assumptions: first, that art residencies originated as a Western phenomenon in the Modern era; and second, that their genealogy is inherently tied to the production of artistic objects.

In light of these considerations, several questions emerge. How might we challenge and expand the dominant narratives surrounding the history of art residencies? What strategies can be employed to amplify perspectives that have been historically marginalized or excluded? And most crucially for our inquiry here, how can this critical reframing lead to the development and recognition of context-specific methodologies that are rooted in situated knowledge and epistemologies?

Reimagining of art residency histories

Although formalized art residencies did not exist in early mediaeval Islam, spaces that articulated the relationship between knowledge, creativity, and journeying nonetheless flourished. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the rihla – a practice of travel as a method for acquiring and transmitting knowledge – emerged as a distinctive intellectual and creative tradition. This practice developed in conjunction with the halaqahs, or study circles, which were established in major Islamic urban centres in Al-Andalus and North Africa. These gatherings brought together generations of scholars – the raḥḥālas – whose primary vocation was to seek, collect, and compare various strands of knowledge by travelling extensively across the Muslim world. Although the raḥḥālas were not ‘artists’ in the contemporary sense, their modes of knowledge production and expression (such as travel writing, calligraphy, cartography, illuminated manuscripts, topopoetic descriptions or diagrammatic thinking) often intersected with what we now consider artistic practices, especially when seen through the lens of artistic research.

How might we challenge and expand the dominant narratives surrounding the history of art residencies?

The raḥḥālas’ lifelong journeys, often undertaken on foot, followed intricate networks of trade routes connecting sub-Saharan Africa with North Africa, the Mediterranean, and across the Sahara. In their journeys, walking was not merely a means of transportation but a core epistemological and cultural practice that facilitated the circulation of ideas, texts, and artistic traditions. From the eleventh century onward, this embodied mode of inquiry provided the foundation for the development of the rihla as a literary genre.

The rihla reached its literary and philosophical zenith in the works of Ibn Jubayr, who formalized the genre, and most famously in the expansive travels of Ibn Battuta. Far from being mere travelogues, these narratives combined poetic sensibility with acute social observation, offering valuable insights into the historical, cultural, and political conditions of mediaeval Islamic societies. As such, the rihla stands as both an artistic and intellectual form, one that continues to inform our understanding of mobility, knowledge production, and intercultural exchange in premodern contexts.

Trans-Saharan trade route map, elaborated by Carlos Perez Marin with the collaboration of Amado Alfadni, Eleonora Castagnone, and Pau Catà in the context of the project Beyond Qafila Thania.

Photograph by Abdeslam Khelil, acquired in 2018 at the artist’s gallery on Rue Didouche Mourad in Algiers.

Considering this historical context, might the rihla and the halaqahs be understood as early forms or conceptual precursors to our contemporary art residencies? What insights might emerge from attending to the temporary dwellings and embodied, slow travel practices of the raḥḥālas – such as walking across regions within and beyond the Arab world? And how might revisiting these itinerant modes of knowledge acquisition, cultural exchange and creative endeavours help us trace resonances with, or offer alternatives to, prevailing models of artistic mobility today?

Moving knowledges: Towards a speculative Arab art residency proto-history

With these interests guiding my inquiry, and motivated by a desire to explore innovative approaches and embrace methodological experimentation, I embarked on a practice-led doctoral journey at the University of Edinburgh and the Edinburgh College of Art. Over the course of five years of research undertaken within this doctoral programme, I developed a counter-history of art residences, which challenges Western-centric narratives by engaging with diverse travel traditions rooted in mediaeval Islamic, as well as modern Arab and Ottoman, cultural contexts.5 The project, which was accompanied by the digital platform “An Event Without its Poem is an Event that Never Happened”, created in collaboration with the Moroccan curatorial duo Untitled, adopted a context-specific methodology seamlessly blending artistic research methods and Islamic research principles.6 While adopting Halaqah as a research framework the study included creative auto-ethnography, semi-fictional micro-narrative, and speculative genealogy, facilitating interaction between textual, graphic, and audio-visual materials.7

The alternative journey proposed in “An Event Without its Poem is an Event that Never Happened” transported the reader through the scholarly circles of eleventh-century Damascus, orchestrating encounters with the first rihla tourists amidst the expanses of the Arabian desert, immersed the narrative in the vibrant literary salons of the fifteenth-century Ottoman Empire, and traced the journeys of scholars from Marrakech and Cairo to the intellectual epicentres of London and Paris during the modern era. This captivating voyage ended with an exploration of art colonies in the late nineteenth century, widely regarded as the inception, as currently suggested, of the history of art residencies. Furthermore, to establish connections between the past and the present, my research suggested a genealogy that engaged Arab scholarly, creative and religious practices with contemporary artistic and curatorial projects developed in the cultural landscapes of the Maghreb and the Mashreq. While offering an alternative to dominant narratives, the project also proposed new methodological, theoretical, and conceptual pathways – ones that bridge past and present, tradition and innovation.

A central concern that emerged throughout my research was the pervasive influence of Western-centric frameworks, which not only shaped the history of art residencies but are also embedded within research methodologies. If my goal was to reweave this history through the slow, reflective travel practices of Arab scholars in mediaeval Islam, then a key question followed: could their ways of moving, dwelling, and knowing also inform the way I conducted research myself?

This inquiry prompted a deeper engagement with context-specific methodologies. These are approaches that are not simply applied externally but arise organically from within the epistemic traditions I sought to explore. What follows is an invitation to explore cross-cultural hybridizations within research methodology, aiming to weave connections between domains that, though they may seem unrelated, might hold more in common than we expect.

Methodological journeys: On the quest for epistemic resonances

Like many journeys, my doctoral research was initially guided by the practice of mapping. The origins of this project can be traced back to the creation of the NACMM (North Africa Cultural Mobility Map).8 This initiative was developed in response to a critical gap: the lack of visibility of contemporary art residencies in North Africa within global residency networks. What began as an effort to address this absence evolved into a comprehensive information platform of cultural mobility in the region. NACMM mapped seventy art residency programs and included a rich collection of more than forty video interviews with artists, curators, researchers, and residency coordinators from the region. It also offered a curated list of over twenty funding bodies and a searchable database of ninety entries dedicated to residency and mobility initiatives for artists, writers, and researchers interested in working in or with North African contexts. This platform was developed in collaboration with several prominent art residencies in the region, including Le18 in Marrakech, L’Atelier de l’Observatoire in Casablanca, Maison de l’Image in Tunis, El Madina in Alexandria, and Jiser in Barcelona.

The resonances between contemporary mapping strategies – particularly post-representational cartography – and early mediaeval Islamic travel narratives rooted in the al-Khabar tradition offer fertile ground for reimagining research methodologies that traverse and interweave diverse epistemic traditions and temporalities.

While the project initially began as a data-gathering initiative, it soon became evident that a more nuanced, qualitative approach was essential to fully grasp the complexities of cultural mobility in the region. The act of mapping and documenting residencies revealed not just infrastructural gaps, but also rich, context-specific practices and narratives that resisted easy categorization. This foundational work therefore became more than a survey – it emerged as a critical lens through which to question dominant frameworks and reimagine research methods. In doing so, it laid the groundwork for a broader project, shaping its methodological direction and anchoring its conceptual concerns in lived, localized experience. This is how NACMM evolved into Kibrit, a collaborative research and production programme dedicated to contemporary artistic and curatorial practices engaged in processes of reactivation of cultural heritage and collective memory in the Maghreb and Mashreq. Kibrit proposed collaborative cartographies, tandem residencies, artistic interventions, exhibitions, public programmes, screenings, and a web platform. Involving all NACMM partners and their respective local communities, Kibrit ultimately aimed to foster sustainable synergies through the exchange of practices, knowledges, and experiences. At its core was a commitment to collaborative historical research, which served as a common ground for connecting diverse contexts and reactivating shared cultural memory.

One of the initiatives developed within Kibrit was Platform Harakat (2017-2024). Named after the Arabic word for “movements,” Platform Harakat emerged to transform cartography into a qualitative, creative, and intimate exercise. Adopting a cross-disciplinary approach, Platform Harakat set out to retrace both historical and contemporary patterns of mobility within the southern Mediterranean region. The platform aimed to activate concepts and practices surrounding mobility – understood not only as physical movement, but also as a social, cultural, and political condition. By documenting forgotten histories and overlooked narratives, Platform Harakat sought to shed light on the entangled legacies of displacement, exchange, and resistance that shape the region. At its core, the platform functioned as a space for critical reflection and collective action, fostering dialogue among artists, researchers, and communities engaged in rethinking the politics and poetics of mobility.

In resonance with the spirit of this multifaceted initiative, I now turn to one of the projects developed within Platform Harakat: Beyond Qafila Thania. By focusing on this project, I aim to begin unpacking the speculative hybridization of two distinct yet conceptually aligned methods: post-representational cartography, grounded in Western critical theory, and al-Khabar narratives, rooted in Islamic research traditions.

Beyond Qafila Thania: Walking as a way to map immediate and preterit empathies

Placed in between a decaying nomadic culture and its exploitation as the ultimate tourist destination, the Saharan desert continues to be a space heavily connoted with a stereotypical imaginary. Self-consciously located at the borders of this juncture, Beyond Qafila Thania brought together researchers and artists from Sudan, Morocco, Spain, Catalonia, Italy, and the Netherlands researching in architecture, sociology, and the visual arts, to actively approach the cultural, social, and geopolitical space of the Sahara Desert. Initiated by Platform Harakat in collaboration with Project Qafila and Le18, Beyond Qafila Thania aimed to trace the historical routes and stories of the old caravans to explore their lasting influence and resonance within contemporary cultures and societies.

Expanding from March to December 2017, Beyond Qafila Thania unfolded as a polymorphous, process-based project encompassing archival research, fieldwork, a nomadic residency, a publication, and a final public presentation. It offered an embodied and speculative approach to Saharan trade routes, merging artistic research with situated knowledge and lived experience. At its core, the project aimed to explore epistemic resonances and diachronic empathies – foregrounding the relational, temporal, and affective dimensions of knowledge production across space and time.

A crucial aspect of the project was a walking residency that partially retraced one of the historic Trans-Saharan trade routes – specifically, the mediaeval route connecting Marrakech to Timbuktu. Lasting ten days and covering the two hundred kilometres between M’hamid and Tisint in southern Morocco, the residency’s participants walked in the footsteps of old trans-Saharan caravans, stopping at several ancient zawiyah, qubbas, and souks along the way. In retrospect, the project also became a journey to partially recover the trans-Saharan trajectories of the rihla, evoking the everyday life of the rahḥạ̄las.

Beyond Qafila Thania should be understood as an effort to decentre artistic production and deconstruct conventional research methodologies, creating a space of in-betweenness – one that resists epistemological certainties and embraces ambiguity. Framed within a phenomenological approach to knowledge production, the act of walking emerged as a generative, embodied practice. It opens alternative ways of perceiving our surroundings, our group dynamics, and our own subjectivities.

Post-representational cartography and al-Khabar narratives

Beyond Qafila Thania’s walking residency ultimately gave rise to a methodological proposition: to deepen epistemic dialogue through embodied practice. As my doctoral research unfolded, my participation in and documentation of Beyond Qafila Thania in the form of creative writing, sound, and audiovisual material (some of which accompanies this article), came into focus as the enactment of a methodology shaped by a subtle interplay between contemporary artistic research and Islamic principles of inquiry. The resonances between contemporary mapping strategies – particularly post-representational cartography – and early mediaeval Islamic travel narratives rooted in the al-Khabar tradition offer fertile ground for reimagining research methodologies that traverse and interweave diverse epistemic traditions and temporalities. In what follows, I explore the intersection of these two temporally distant yet methodologically resonant approaches. Through this comparative lens, I seek to articulate the possibilities of hybrid methodologies – those capable of unsettling dominant frameworks and making space for plural, contextually grounded ways of knowing.

It is only by unsettling the grounds on which established discourses currently stand that epistemic diversity emerges.

The work of Sébastien Caquard and William Cartwright played a pivotal role in shaping my exploration of post-representational cartography as a research methodology. According to them, post-representational cartography asserts that “maps are never finished but are in a constant process of becoming. They come to life throughout the map-making process, as well as through their use in a specific context with a specific purpose.”9 Caquard and Cartwright perceive cartography not solely as a means of conveying spatial information but also as a catalyst for emotional journeys. As they argue, “on a personal level, maps can serve as a therapeutic and healing process. While on a collective level, maps can contribute to leaving cartographic traces, making these experiences more visible and tangible.”10 In line with this perspective, mapping is not merely seen as a political process of constructing meaning but also as a tool for self-reflection. Indeed, since the 1980s, critical cartographers have revealed the concealed narratives of power and control inherent in historical and contemporary maps, fostering alternative mapping approaches. Laden with political significance, these alternative forms offer diverse viewpoints on landscapes, territories, and their histories. To this stance Caquard and Cartwright add a creative dimension which includes intimate interpretation. This critical approach towards cartography and its representational drive forms the foundation of post-representational cartography.

While the adoption of post-representational cartography initially appeared promising as a methodological framework, the aim of my dissertation was not to pursue fixed conclusions but rather to challenge and unsettle established knowledge paradigms. Central to this approach was a commitment to context-sensitive research methodologies, ones that draw on the productive tension between innovation and tradition, the contemporary and the historical. In this spirit, I turned to cartographic practices and their epistemic legacies, focusing on al-Khabar travel narratives as cultivated by the rahḥạ̄las of early mediaeval Islam.

As the scholar of religion Travis Zadeh contends, the term al-Khabar signifies the presentation style of travel narratives within the biographical genre in early Islamic cultures.11 These narratives, central to the creative practice of the riḥla as literary genre, utilized diverse techniques, such as direct speech, dialogue, and vivid descriptions, to impart a sense of authenticity. The narrative style, characterized by its dramatic blend of description and dialogue, adhered closely to specific discursive norms. Through the meticulous attention to detail and the emphasis on eyewitness authority, the framework of al-Khabar’s travel narratives provides valuable insights into the past. Expanding upon Zadeh’s analysis, the anthropologist Houari Touati posits that al-Khabar narratives challenge conventional cartographic interpretations.12 Touati argues that these narratives not only situate the journey within an anthropology of gaze but also offer a framework for understanding the interplay between the human and the non-human. Furthermore, they introduce literary motifs that contribute to the evolving field of geography through imaginative storytelling, blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction.

Walking the unmapped

As is often the case, a deeper understanding of a journey only crystallizes in retrospect. This is what happened in the case of Beyond Qafila Thania. Although the project did not impose any obligation to produce concrete artistic outcomes, each participant, in their own way, felt compelled to document the journey. While fragments of these reflections are captured in the project’s final publication,13 the following excerpts from my personal notes aim to expand upon that record. They offer an attempt to situate my practice within the broader framework of the project and to trace the resonances it evoked – through the lens of lived experience, embodied inquiry, and affective engagement. Is it possible to understand this resonance also as a dialogue between post-representational cartography and al-Khabar travel narratives?

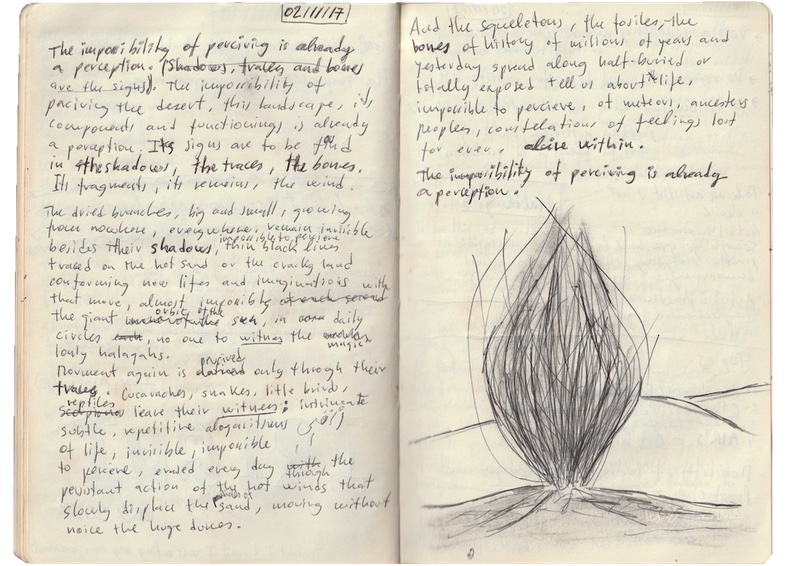

Pau Catà's diary

Southern Moroccan desert

4 November 2017

The impossibility of perception is a perception in itself.

The impossibility of perceiving the desert, this landscape, its components and functioning, is already a perception. The signs are to be found in its traces: the remaining fragments, the fragmented remains, its bones.

The dried branches, big and small, growing from nowhere, everywhere, impossible to perceive, remain invisible beside their shadows: thin black lines traced on the hot sand or the cracking land, forming new lives and phantasmagorias, move almost impossibly with the giant orbit of the sun, tracing daily circles, no one witnessing the lonely halaqahs.

Movement is perceived through its traces. Cockroaches, snakes, little birds and reptiles leave their testimony: an intricate, subtle, repetitive algorithm of life, impossible to perceive, erased every day through the persistent action of the Saharan winds that slowly displace the particles of sand, moving the vast dunes silently.

And the skeletons, the fossils, the bones of millions of years of history and yesterday, half-buried or totally exposed, tell us about the fragility of life, of meteors, ancestors, and peoples, impossible to perceive.

Southern Moroccan desert

3 November 2017

Are we walking too much? How can suffering become fruit? Is this state a path? We indeed taste the limits, live them in each step, traversing arid lands, killing the snake to welcome the crow. Alone, without words, too exhausted to talk. Are we walking too much? How can suffering become fruit? Is exhaustion the path? Deep within the branches, the wind gives its silent answer: a constant warm whispering, quiet and persistent, following our walking together apart.

Southern Moroccan desert

1 November 2017

Man is also fragile here. One more element of a landscape to which we all must adapt, temporarily or perpetually. However diverse they may be, strategies of adaptation share common aspects. These are submission and respect towards that which is visible and to the invisible and resilience and patience where progress and hurry are to be neglected.

Sand is made into mud, mud into a house, the house into a carpet, the carpet into a starry sky, the starry sky into a sea of black rocks, the black rock into a camel, the camel into a haima, and the haima into golden dunes, sand, the desert.

+++

Framed by the experience of walking, the desert became a catalyst to enhance new and ancient ways to understand the landscape. A space away from conceptual and methodological comfort zones. A journey to oneself with no need for images to be made.

Physically, the desert showed us its traces, its shadows, and its remains as the tools from which to start understanding that these subtle signs are its ethos. Conceptually, these traces, shadows, and remains became also alternative forms of knowing.

Envisioning hybrid intellectual heritages through artistic research

In exploring the intersections between al-Khabar’s travel narratives and post-representational cartography, it is imperative to recognize that the objective of my doctoral research and this text extends beyond establishing a direct correlation between the two. Rather, the purpose is to encourage further scholarly inquiry and provoke contemplation regarding potential pathways for enhancing what could be construed as hybrid intellectual legacies. By drawing parallels between these seemingly disparate yet inherently interconnected realms, this text seeks to illuminate nuanced understandings of both historical and contemporary modes of spatial representation through artistic research. Its aim is to spark conversations that transcend conventional disciplinary boundaries, fostering interdisciplinary dialogues that enrich our collective appreciation of diverse cultural and intellectual traditions.

Artistic research, with its embrace of speculative thinking, offers a vital approach to examining the evolving landscape of knowledge production. It foregrounds the dynamic interplay between diverse intellectual heritages and highlights the potential of methodological hybridization to generate new insights and perspectives. While an in-depth exploration of the historical interconnections between al-Khabar narratives and post-representational cartography lies beyond the scope of this essay, the possibilities it opens for future inquiry are undoubtedly compelling. Artistic research operates holistically, experimentally, and through embodied practice, offering alternative modes of inquiry that invite more expansive forms of understanding. Integrating such approaches alongside conventional historical methodologies enables a richer exploration of the relationships between narrative, representation, and spatial imagination.

This juxtaposition becomes particularly relevant when rethinking the dominant, often Western-centric narratives, such as the one affecting the history of art residencies. As these histories continue to be reproduced through institutionalized frameworks, it becomes imperative to challenge and expand them. In doing so, this essay advocates for the adoption of context-specific methodologies rooted in situated knowledge and local epistemologies – approaches that honour plural histories and the multiplicity of ways in which knowledge is lived, embodied, and transmitted.

As the Congolese philosopher Valentin-Yves Mudimbe states, “stories about others, as well as commentaries on their differences, are but elements in the history of the same and its knowledge.”14 Indeed, it is only by unsettling the grounds on which established discourses currently stand that epistemic diversity emerges. Through a case-study, this text has wanted to stress that the potential of a common future, within and beyond the research field, requires the enhancement of our hybrid pasts.

Glossary of terms

Riḥla (رِحْلَة): Arabic term meaning journey or travel. In the context of classical Islamic culture, it refers both to the act of travel and to a distinct literary genre that documents such travels, often blending personal narrative with scholarly observation.

Raḥḥāla (رَحَّالَة): Refers to a traveller, explorer, or itinerant scholar, particularly within the context of mediaeval Islamic culture. The term is derived from the Arabic root r-ḥ-l (ر-ح-ل), meaning “to travel” or “to journey”.

Halaqah ( حَلَقَة, literally meaning circle or gathering): Refers to an informal study circle traditionally held in mosques or learning centres, where a teacher and students sit in a circular formation to engage in religious, philosophical, or literary discussions.

Zāwiyah ( زاوية, plural: zāwiyāt): Religious, educational, and spiritual institution commonly associated with Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam. The word literally means “corner” or “niche”, symbolizing a retreat-like space for contemplation and learning, often physically located at the edge or corner of a community.

Qubba ( قُبَّة, plural: qubbāt or qubab): Refers to a domed structure, typically built over the tomb of a revered figure, such as a Sufi saint, scholar, or important community leader. The word qubba literally means “dome” in Arabic, but it has come to signify the entire shrine or mausoleum complex.

Souk (also spelled suq, souq, or sūq): Traditional marketplace or commercial quarter found throughout Arab and Islamic cities.

Haima (also spelled khaimah, khaima, or khayma, خيمة): Tent used by nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples across North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and parts of the Middle East and Central Asia.

+++

Pau Catà

is a Barcelona-based artist, curator, and researcher. He holds a practice-led PhD in Art from the University of Edinburgh. He has been the coordinator of CeRCCa (Centre for Research and Creativity Casamarles) and Platform Harakat, and is a founding member of ARRC (Art Residency Research Collective).

Unless otherwise stated, all images are by Pau Catà.

Footnotes

- The works referenced here are: Ptak, Anna, ed. Re-tooling Residencies: A Closer Look at the Mobility of Art Professionals. Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle and A-I-R Laboratory, 2011; Ostendorf, Yasmine. ON-AiR: Reflecting on the Mobility of Artists in Europe. Ed. by Maria Tuerlings, Trans Artists, 2012; Cámara, Raquel, ed. Mapping Residencies. vol. 2, 2015; Pissaride, Iris, ed. Unpacking Residencies: Situating the Production of Cultural Relations. Series: Kunstlicht, vol. 39, no. 2, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2018; Conte, Kari, and Susan Hapgood, eds. Bringing Worlds Together: A Rethinking Residencies Reader. Rethinking Residencies, 2023; Mendrek, Pawel, et al., eds. On Care: A Journey into the Relational Nature of Artists’ Residencies. Vfmk, 2024; and Kokko, Irmeli, ed. Residencies Reflected. Mousse Publishing, 2024. ↩

- Policy Handbook on Artists’ Residencies: European Agenda for Culture: Work Plan for Culture 2011–2014. European Commission Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2016. ↩

- Elfving, Taru, and Irmeli Kokko. “Reclaiming Time and Space. Introduction.” Contemporary Artist Residencies: Reclaiming Time and Space, ed. by Taru Elfving, Irmeli Kokko, and Pascal Gielen, Valiz, 2019, p. 9. ↩

- Kokko, Irmeli, in Bringing Worlds Together, p. 16. ↩

- Catà Marlès, Pau. Moving Knowledges: Towards a Speculative Arab Art Residency Proto-History. 2021. Edinburgh College of Art Thesis and Dissertation Collection, era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38491. Accessed 14 Apr. 2025. ↩

- Catà Marlès, Pau, et al. “An Event Without its Poem is an Event that Never Happened.” 2021, aneventwithoutitspoem.com. Accessed 15 July 2025. ↩

- Ahmed, Farah. “Exploring halaqah as research method: A tentative approach to developing Islamic research principles within a critical ‘indigenous’ framework.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 27, no. 5, 2014, pp. 561-83. ↩

- North Africa Cultural Mobility Map. NACMM, 2017. www.paucata.cat/complicities/nacmm. Accessed 15 July 2025. ↩

- Caquard, Sébastien, and William Cartwright. “Narrative Cartography: From Mapping Stories to the Narrative of Maps and Mapping.” The Cartographic Journal, vol. 51, no. 2, 2014, pp. 101-06. doi.org/10.1179/0008704114Z.000000000130. Accessed 14 Apr. 2015. ↩

- Caquard and Cartwright, p. 104. ↩

- Zadeh, Travis. Mapping Frontiers Across Medieval Islam: Geography, Translation and the ’Abbasid Empire. Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. ↩

- Touati, Houari. Islam and Travel in the Middle Ages. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. University of Chicago Press, 2010. ↩

- Catà Marlès, Pau. Beyond Qafila Thania: Walking as immediate and preterit empathy. Interartive Walking Art / Walking Aesthetics, 2018, walkingart.interartive.org/2018/12/Beyond-Qafila-Thania. Accessed 14 Apr. 2025. ↩

- Mudimbe, Valentin-Yves. The Invention of Africa. Indiana University Press, 1988. ↩