Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 32 nr. 2, pp. 26-35

"Latent space" in artistiek onderzoek. Een doorlopend paradigma voor en na AI

Veronica Di Geronimo, Andrea Guidi

This article proposes reframing latent space – originally a technical term in artificial intelligence – as a methodological archetype capable of capturing key dynamics within artistic research. In doing so, it also problematizes the epistemological boundaries and peculiarities underlying both AI and artistic research. We also introduce the AI-mediated platform °’°Kobi, which functions as an epistemological tool that closely resonates with artistic research understood as a latent space – non-linear, emergent, and driven by associative processes.

Dit artikel stelt voor om latent space – oorspronkelijk een technische term uit de kunstmatige intelligentie – te herdefiniëren als een methodologisch archetype dat in staat is om belangrijkste dynamieken binnen artistiek onderzoek te vatten. Daarbij worden ook de epistemologische grenzen en eigenaardigheden van zowel AI als artistiek onderzoek ter discussie gesteld. Daarnaast introduceren we het AI-gemedieerde platform °’°Kobi, een epistemologisch instrument dat nauw aansluit bij artistiek onderzoek, opgevat als een latente ruimte – niet-lineair, emergent en gedreven door associatieve processen.

I am somewhere between happy and happier

when my data is dada and when 1+1= 0.

– Ian Andersen1

Introduction

In the era of artificial intelligence (AI), philosophers, media theorists, and art historians are collectively rethinking models of creativity, often coining new terms to register technological change.2 While identifying new terms can be useful to capture epistemic shifts, this article turns to an existing one – latent space – to show how a concept native to AI can shed light on certain dynamics by which artist-researchers produce knowledge.

In AI, a latent space can be imagined as a space composed of various items (such as texts, images, or sounds) that encodes their potential connections or similarities; algorithms traverse this map to discover or synthesize new combinations and generate outputs. Transposed to artistic research, the notion operates to describe a symbolic domain of creative potential, where ideas and knowledge emerge through indeterminacy and recombination, leading to original creations and new forms of knowledge, thanks to a reservoir of sedimented materials – styles, data, cultural expressions, forming the basis of collective, distributed creativity.

This framing raises our article’s guiding research question: How can the AI-derived notion of latent space illuminate the tacit reasoning that artists employ, including intuitive leaps, associative recombinations leading to ideas and knowledge production through practice? To what extent does it mirror artistic research processes?

The idea of latent space as a ‘platform’ opens a broader reflection on its epistemological status that resonates with some methodological characteristics of artistic research.

The questions are addressed in two parts. Part I discusses the transferability of the latent space notion to the arts domain. By tracing historical precedents – from Dada’s proto-algorithmic cut-ups, through Pataphysics’ “science of imaginary solutions,” to modern times – the section shows that the term can be a productive interpretive lens even for artistic endeavours that long pre-date contemporary AI. Part II turns from theory to practice, analysing °’°Kobi, an AI-driven platform developed at the Academy of Fine Arts of Rome in collaboration with Marche Polytechnic University. °’°Kobi juxtaposes the computational latent space of a large language model with the users’ evolving cognitive latent spaces which we may describe as the idiosyncratic webs of memory, perception, disciplinary and embodied knowledge that each artist brings to the encounter. Interaction logs and post-session reflections reveal how this cross-navigation surfaces (and sometimes constrains) the intuitive leaps, associative recombinations, and emergent patterns that characterize artistic research.

In the last sections of the article, we critically discuss both the explanatory power and the practical limits of latent space as a metaphor for grappling with the tacit, non-linear dynamics of artistic research – exemplifying intuitive leaps, associative recombinations, and emergent patterns while also exposing the constraints imposed by algorithmic logic, representational flattening, and the irreducible situatedness of human artistic practice.

Part I

Theoretical Framework: Latent Space and Artistic Research

Latent space is a statistical and computational concept that represents the hidden variables or underlying structures within observed data. In machine learning, this notion refers to a multidimensional space in which digital objects – such as images, text, and sounds – are transformed into embeddings, that is, dense numerical vectors capturing their relevant features. These embeddings are generated through training processes that allow models to capture and compress patterns in the data into lower-dimensional representations, preserving semantic relationships in terms of proximity and distance within the latent space. Latent spaces are commonly constructed using architectures such as autoencoders, a neural network consisting of an encoder and a decoder developed to compress data into a lower-dimensional representation.3 Conceived for dimensionality reduction and efficient information retrieval, these models are designed to learn the most salient and generalisable features of the data, thereby performing an operation of abstraction that can be seen as a form of affective and symbolic labelling.4

Among the various types of autoencoders, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) introduce a probabilistic structure that makes them particularly suited for generative tasks, enabling the model to produce plausible new outputs by sampling from a continuous distribution within the latent space.5 Thanks to this type of autoencoder, which acts as a mediator between raw data and its vector representation, the latent space becomes a repository for a vast and diverse array of embedded information that informs and shapes the content generated by AI. This information, when encoded and decoded using a shared numerical representation – often achieved through techniques such as contrastive learning – can facilitate multimodal interplay between images, text, sound, and other forms of expression. In this sense, latent spaces enable multimodal transitions between visual and textual codes allowing the relationship between the visible and the sayable to be reconfigured.6 They come to symbolize a domain of connectivity and creative potential, “where the coordinates of all possible outcomes are delineated.”7

What makes latent space particularly significant to the discussion on the artistic research paradigm is its metaphorical image as a thesaurus of potentialities – a dynamic magma of meanings and forms not yet actualized, but existing in a state of virtual readiness.

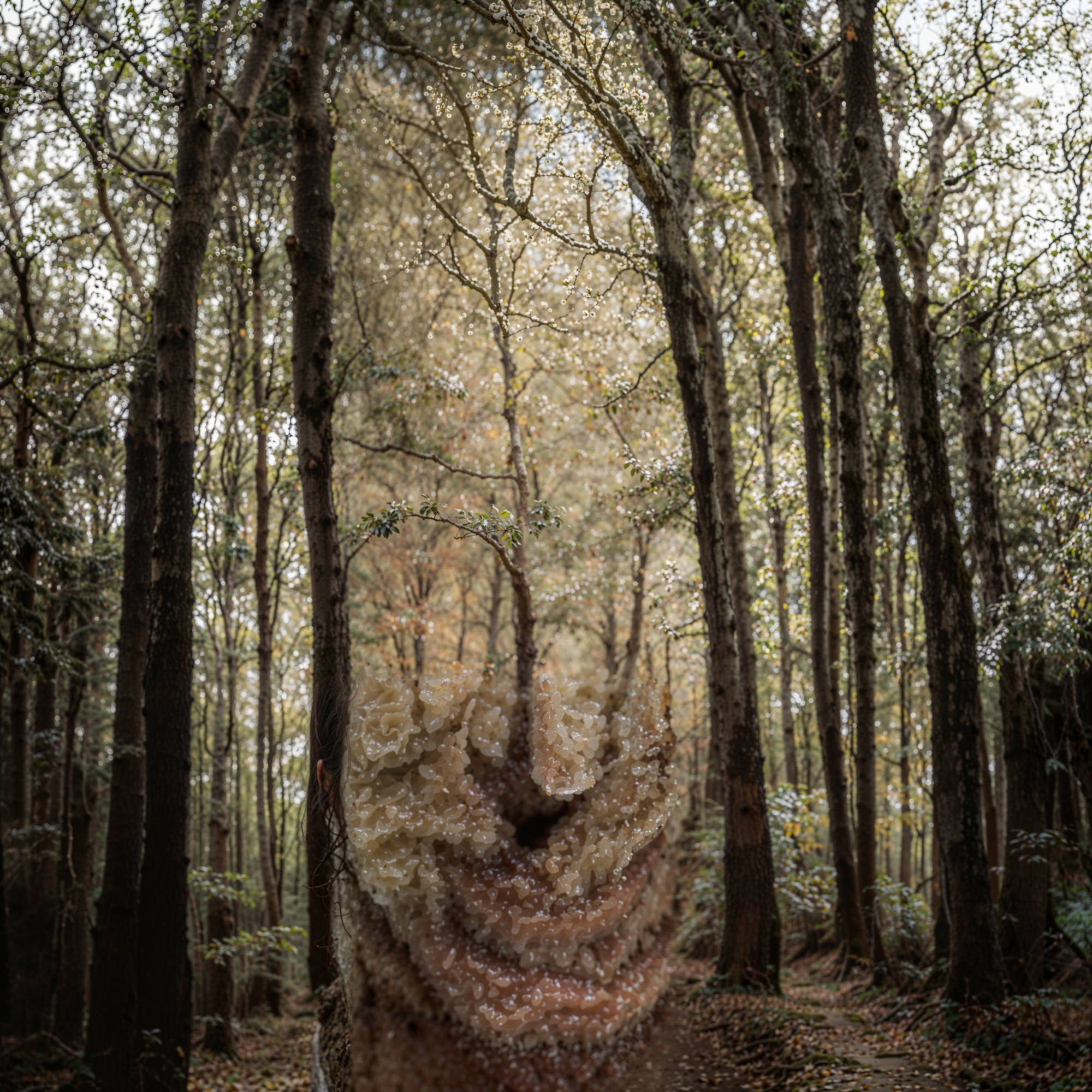

However, this symbolic field of potentialities should not be understood as absolute, since it is shaped by training data, conditioned by biases and influenced by statistical functioning. These characteristics of the AI latent space led artists to engage with it as both a site of unexplored possibilities and a terrain already deeply inscribed with constraints. For instance, 3402 Selves (Fig. 1) by Francesco D’Abbraccio (also known as Lorem) explores the expansion of facial datasets by analysing the proximities and distances between data points and their gradual transformation by the relationship between musical rhythm and visual resemblance. Faster rhythms generate faces that appear more similar, while slower rhythms produce images derived from more distant data points, thereby emphasizing greater variation – effectively rendering visible the results of a flânerie through latent space.

Fig. 1: Francesco D’Abbraccio (Lorem), 3402 Selves, Images from Lorem’s video 3402 Selves, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 2: Francesco D’Abbraccio (Lorem), Distrust Nature #003. From the Distrust Nature series, 2020, Fine-art print on aluminium, 100x100 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Latent space, understood as a domain that reflects the intricate and dynamic nature of the creative process, has already attracted academic attention and inspired various software developments. Companies at the forefront of AI for audiovisual creation propose prototypes that reimagine creativity as an interactive search through latent space, where ideas unfold as graphs of nodes and paths, blending intentional design with unexpected discovery in a flexible, non-linear artistic exploration.8 Similarly, scholars have discussed the capacity of latent spaces as a generative instrument expanding the artistic process of different kinds of arts.9 In music, researchers have recently described latent spaces not merely as a mere representational structure, but also as platforms – exploiting the term’s ambiguity in a metaphorical sense to allude to configurable, dynamic environments that support co-creative exploration and sonic improvisation.10

The idea of latent space as a ‘platform’ opens a broader reflection on its epistemological status that resonates with some methodological characteristics of artistic research. The sui generis nature of artistic research methodology has been a central topic of debate, especially in comparison with hard sciences and the artistic research relevant institutionalization process.11 The rejection of rigid, straitjacketed methods in favour of methodological heterogeneity and open-ended, non-predetermined processes has positioned artistic research as a significant point of reference for other disciplines.12 Its methodology has been characterized as a combination of a wide range of elements in a non-linear and exploratory mode of inquiry, a tapestry-like weave of many factors: the read, the known, the observed, the created, the imagined, and the deliberate.13 As existing literature notes, artistic research generates a space for not knowing – or not yet knowing – a conceptual room14 that operates through erratic method, which involves unpredictable actions and therefore some degree of randomness.15

Artistic enquiry operates within the uncertain zones of intuition and provisional practice, transforming tacit or embodied knowledge into an explicit understanding. As an emerging form of research, it demonstrates a research approach in which creation and action become ways of acquiring and shaping knowledge. Other forms of research articulation may supplement or integrate with this form of material thinking, but can never fully substitute for it.16 In fact, practice-led research has developed into a distinct paradigm, now recognized alongside quantitative and qualitative approaches. It is characterized primarily by the centrality of practice, not merely as an object of study, but as the driving force and method of investigation, which results in expressions through non-discursive symbolic forms such as performance, visual art, sound, dance, or digital media.17 Consequently, the iterative character of artistic research – with its productive uncertainty and its resistance to deterministic models of knowledge – points to the existence of each artist’s metaphorical “latent space.” Here, “latent” signals that beyond what is currently perceived or seen, there is always something still undiscovered from which new creation can spring.

Historical Antecedents of Latent Space Mechanisms

An early recognition of art as an epistemic model came from the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend. In Against Method (1975), he turned to the subversive spirit of Dadaism and its capacity to introduce a novel, disruptive approach to questioning the dogmas of scientific research. He described the avant-garde movement as a form of ‘epistemological anarchism’, a way of thinking that rejects fixed methods and encourages freedom in the creation and understanding of knowledge.18 However, a closer look at the Dada Manifesto reveals an attitude that, paradoxically, resists the very notion of spontaneous or anarchic creation, suggesting a stereotype according to which artistic method was considered lacking in structure. Tristan Tzara has transcribed a series of step-by-step instructions – sequentially ordered – that serve as a clear compositional guide, a procedural logic, functioning as a kind of proto-algorithmic approach.19 The creative process outlined in the Dada Manifesto, positioned at the interplay of procedural logic and unpredictability, anticipates the dynamics of latent spaces – domains where inputs generate unforeseeable outcomes through recombination and abstraction.

A similar rupture with conventional logic underpins Pataphysics. Conceived by French writer Alfred Jarry, Pataphysics is defined as “the science of imaginary solutions” – a field based on exceptions and unconventional reasoning. Jarry described it as an epiphenomenon of metaphysics, both parodying and critiquing scientific methods. It challenges rational thought and embraces paradox, nonsense, and the irrational. Pataphysics blends internal impulses with external influences, unfolding through dissonant elements and unexpected connections. It highlights creativity and the value of anomalies, offering a speculative, imaginative alternative to normative systems of creation.20 In fact, Pataphysics has become a paradigm for computational and digital creativity. By embracing exceptions and paradoxes, it offers a model for rethinking creative inquiry beyond conventional logic. In information retrieval systems, its approach informed concepts like patadata – a form of metadata designed to favour serendipity and exploration over precision in web search engines.21

The generation of novel combinations of ideas presupposes a rich and diverse knowledge pool or storage.22 As highlighted in the entry Creativity in the Future from the Encyclopedia of Creativity (2020), creativity is increasingly understood as a shared and relational process. Although its collective dimension has become a defining feature of the twenty-first-century creative landscape,23 it has long operated within networks of exchange, interaction, and material interdependence: “Creativity, like intelligence, is not something which occurs in a vacuum, or in a single mind [...] Creativity has always been a social, interpersonal, and interspecies phenomenon.”24 In the field of music, reflections on how creativity emerges within communities are captured by the socio-cultural concept of Scenius, coined by musician Brian Eno. The term is a playful reworking of “genius,” insisting that major breakthroughs in art, science, and culture often arise from supportive creative communities rather than from solitary artists. This concept, which emphasizes the communal and interdependent nature of creativity – strengthened through collaboration, exchange, and shared contexts – resonates with the way latent space is constructed from the vast amounts of knowledge collected in datasets that inform new outputs.25

Chains of associations: Model for creative thought

Scholars of a certain historical period regarded non-logical process as a key catalyst component in the activation of creative ideas. Among the intellectuals who reflected on the process of achieving ‘eureka moments’ in the bathtub, the French mathematician Henri Poincaré is a central figure. Engaged in a dynamic cultural and intellectual milieu, Poincaré explored the nature of knowledge, articulating his reflections on procedures of scientific discovery in Science and Method. Poincaré regarded mathematical discovery as an act of selection among infinite trivial combinations, requiring the ability to recognize which constructions lead to new understanding and which are mere noise in an infinite space of possibilities. Drawing on his own experience of solving mathematical problems, Poincaré saw research as a process of sudden insight. He recalled a breakthrough that came during a sleepless night after drinking an unusual amount of black coffee. At that moment, a flood of mathematical ideas seemed to compete for attention until, in a spontaneous flash of clarity, two concepts merged into a stable configuration that led to the discovery of a new class of functions.26

AI logic clashes with the epistemologies of embodied and material knowledge-making proper to artistic research.

This idea was further elaborated by Graham Wallas in The Art of Thought (1926). Wallas formalized a four-stage model of creativity, specifically identifying an intermediate phase between problem identification and its resolution: incubation, a period during which unconscious processes engage with the problem and ultimately contribute to the emergence of innovative solutions.27 Shaped by contemporary understandings of the Freudian unconscious, the notion of unconscious incubation resonates with today’s conception of AI as a black box: a system capable of generating novel outputs through opaque, nonlinear associations that elude immediate explanation.

Building on similar premises, Sarnoff A. Mednick (1962) proposed a theoretical model that delineates three distinct pathways through which creative ideas may emerge in associative ways: serendipity, wherein chance encounters facilitate novel associations; similarity, where connections arise through resemblance in structure or meaning; and mediation, in which intermediary elements bridge otherwise distant concepts.28 Mednick linked this associative pattern of creativity to the practice of collage – drawing on Max Ernst’s talent for connecting distant realities through unexpected juxtapositions – in a parallel also echoed by the cognitive scientist Margaret Boden to explain AI creativity. Boden conceptualizes combinational creativity as the ability to generate unfamiliar combinations of familiar ideas, a process that, contrary to common assumptions, remains a major challenge for AI.29

The parallelism that Mednick employs to validate his theory through practical examples – illustrating how creativity arises through associative processes by referencing Einstein, Poincaré, and surrealist painters – suggests this mechanism transcends disciplinary boundaries and underpins creative thought across different domains. These theoretical discussions are reinforced by artists’ accounts of the genesis of their work, which provide first-hand insights into the creative process. A notable example is William Kentridge, who documented the creative process behind his 2016 project Triumphs and Laments in a dedicated volume. The selection of narratives he depicted on the embankment walls of the Tiber stemmed from a reflection on mural techniques – specifically, the negative hydro-cleaning process used to remove the biological patina. As Kentridge observes: “This technique immediately got me thinking about a whole series of other associations and possibilities, of all the multiple histories that are sitting in the grime of the city, waiting to be washed away, to be revealed.”30

This associative process underlying the generation of original ideas for creative and/or artistic projects is also transversal to the techniques and media employed by artists, precisely because it characterizes the initial, pre-project phase of creativity – when ideas are still in their embryonic state, before the unfolding of the research and experimentation phase involving techniques, tools, materials, and environmental conditions that shape the entire process of artistic inquiry. Looking at the Chinese conceptual artist Chen Zhen, who frequently documented his work and creative processes in writings, we find an explicit use of the notion of ‘short circuit’ as creative method: the encounters, overlaps and tangents that gave rise to his installations.31

Part II

Artistic research through AI: The case of °’°Kobi

In recent years, AI has played an increasingly central role in supporting creativity and research. This is not only through generative tools for artistic production, but also by enabling new forms of knowledge discovery. In addition to generative AI models, a growing number of tools have been developed to reveal the associative logic of AI systems and explore the creative potential of latent spaces. These tools function both as navigational aids and as design instruments, allowing users to traverse the latent space using semantic input. In the domain of explainable AI, latent space exploration has also become instrumental in demystifying the black box of complex models, thereby enhancing the understanding of machine reasoning.32 In the field of academic research, a system of AI for managing literature was introduced that could be operationalized as personalized cognitive cartographies for navigating complex information environments.33

°’°Kobi – a platform developed jointly by the Academy of Fine Arts of Rome and the Marche Polytechnic University – has been conceived precisely to serve the distinctive goals of artistic research, aligning with the shared reflective dynamics proposed by Knowledge Ecosystem models.34 By leveraging the linguistic capabilities of large language model (LLM) technology, °’°Kobi supports artistic reflection through the generation of semantic relationships emerging from the platform’s latent space. These relationships serve as a resource for advancing individual artistic research and for exploring a dynamic, interconnected web of knowledge – one that is both navigable and expandable through user contributions. The platform’s name originates from the Greek term Koinobion, meaning “life in common,” which encapsulates the platform’s aim: to cultivate and sustain a shared, evolving body of qualified knowledge that continuously informs and enriches the students and researchers’ creative loop. Central to its operating system is the knowledge base, a structural space of possibilities drawn from the art community itself, utilizing the Research Catalogue repository (the international database for artistic research) as well as other materials that can be directly uploaded by professors and educators. The incorporation of diverse source materials into the common knowledge base contributes to the “situatedness” of the artistic research process.35 When art researchers engage with the platform, they operate within a digitally dense semantic space – one that is constructed upon the background of inter-human knowledge and continuously enriched through collective contributions. This environment allows for context-aware inquiry, where meaning emerges through the dynamic interplay between individual perspectives and shared intellectual frameworks.

°’°Kobi functions as an anomalous knowledge retrieval system to stimulate unconventional and divergent thinking.36 It operates within a complex framework in which diverse materials interact through complementary and antagonistic relationships, fostering emergent and dynamic forms of knowledge production that reflect the non-linear and exploratory nature of artistic research. This approach encourages artists to navigate across fields, discovering affinities between distant domains.

Mechanisms of °’°Kobi’s latent space exploration

The °’°Kobi system deconstructs the texts of the knowledge base into paragraphs and lemmas; this granular fragmentation removes contextual constraints and exploits polysemy and conceptual similarities to generate unexpected associations to be proposed to art students and users. By reorganizing content around semantic nodes, the platform facilitates interdisciplinary connections and fresh perspectives. Like other approaches that leverage computational techniques to emphasize serendipity – such as latent space walking, which enables the exploration of remote and hidden regions of representational spaces – °’°Kobi was developed to support navigation of distant areas of knowledge. Its architecture is grounded in the principles of semantic proximity and distance, allowing users to navigate a knowledge ecosystem in exploratory, non-linear ways. It offers two interfaces for interaction: a conversational chatbot and the Universe, each corresponding to distinct navigable latent spaces.

The chatbot retrieves and presents three content cards with varying degrees of semantic coherence – high, medium, and low – in relation to the prompt. This structure supports non-linear thinking and unexpected connections by encouraging users to engage with content that may fall outside conventional disciplinary boundaries. Alongside the cards, °’°Kobi also provides direct responses, blending guided discovery with generative assistance.

Tests conducted during workshops held with graduate students in a Master’s programme of fine arts indicate that °’°Kobi effectively stimulates divergent thinking, one of the key indicators used in cognitive science to trace creative activity.37 The workshop activity aimed to assess participants’ divergent thinking by observing their interaction with the °’°Kobi AI tool. Participants could consult Kobi for insights on their assigned keywords. Analysis of the chat logs revealed semantic deviations from the initial keywords. For example, one student expanded on the keyword ‘sand’ to explore its relation to ‘ash’, while another shifted from ‘shared space’ to ‘liminal spaces’ and finally ‘disputed spaces’, guided by cues in the AI’s responses.38 These data of user interactions revealed that engaging with °’°Kobi encourages users to depart from initial assumptions and explore unforeseen conceptual paths.

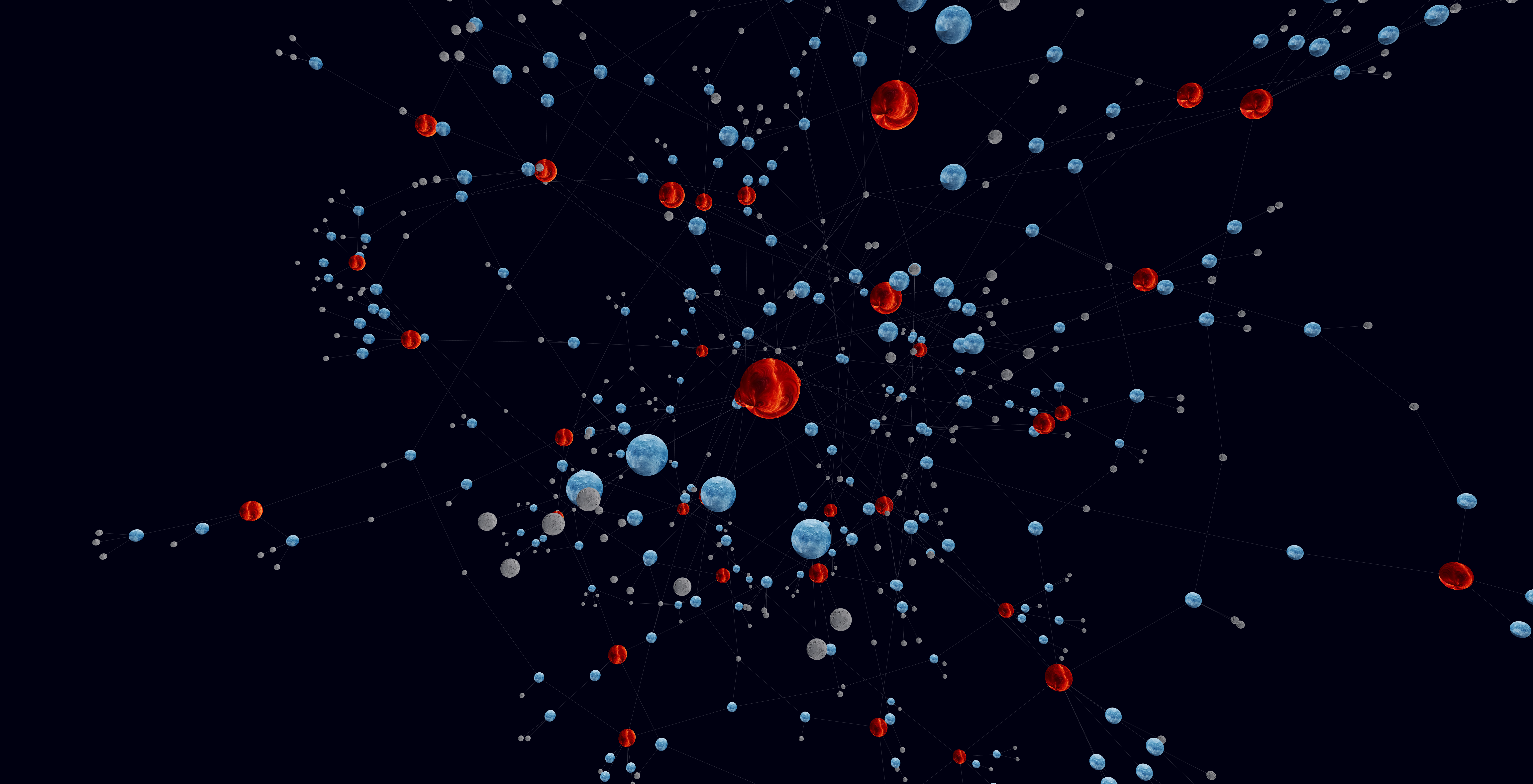

While the contents proposed through the first interface were drawn from entire papers and publications, the Universe is a latent space constructed by extracting lemmas and key concepts from the abstracts of the materials uploaded into the knowledge base. This linguistic space is visualized as a graph representation (Fig. 3), where linguistic nodes form a dynamic network of semantic relationships. Users can freely explore, drift, and meander among these nodes, following intuitive or accidental trajectories. By mapping semantic nodes as interconnected points within a dynamic system, the Universe interface offers a visual exploration of knowledge relationships, where concepts appear as active entities – ready to be accessed, expanded, and recombined. This representation not only reinforces the non-linear and exploratory nature of artistic research but also enhances serendipitous discoveries and new interdisciplinary connections. An approach reconfigures the knowledge retrieval experience into an interactive and heuristic exploration – a latent space navigation within a fluid, stratified, and continuously evolving environment, where knowledge sediments and resurfaces through unforeseen recombination.

Fig. 3: Universe Interface of the °’°Kobi tool (Accessed March 2025).

Discussion

°’°Kobi’s infrastructure proposes a reflexive and evolving system in which the research process is conceived as situated, contingent, and collectively constituted within the dynamics of its AI latent space. This framework resonates with several foundational aspects of artistic research, particularly its emphasis on processuality, openness, and contextual responsiveness. The affinities between the latent space leveraged by the platform and the methodological logic of artistic research can be articulated along five primary theoretical dimensions.

Non-linearity

Artistic research, by its very nature, thrives on open-ended exploration, intuitive inquiry, and the continuous negotiation of meanings and ideas. This methodological openness corresponds to the functioning of latent space in AI – not as a fixed repository of information, but as a dynamic and multidimensional environment in which connections emerge through iterative, often unpredictable processes. Indeed, in contrast to conventional deterministic models of knowledge production that prioritize predictability and control, artistic research and practice has historically embraced glitches, hallucinations and serendipitous deviations as catalysts for innovation.

Combinatory logic

Latent space is a kaleidoscope where everything is potentially interconnected.39 It operates by compressing and reassembling information into new configurations – generating unexpected proximities among distant elements. This logic mirrors the combinatory creativity at the core of many artistic practices and creative process, where meaning arises from juxtapositions, detournements, and short-circuits.

Distributed agency

Artistic research is a polyphony of sources and procedures.40 It is a practice that is inherently situated and embedded – entwined with cultural, historical, social, and economic contexts, as well as with the broader discourse of art.41 Like intelligence, artistic research is not the product of a solitary mind but an emergent property of encounters, experiences, materials, and relationships – long before this interconnectedness was theorized by its community. Consider, for example, the radiance of Fra Angelico’s Early Renaissance frescoes: their brilliance stems not only from the artist’s vision, but also from the presence of cochineal insects, egg-based tempera, sable brushes, lapis lazuli mined in Afghanistan, and the aesthetic and religious sensibilities of the time.42 Similarly, in AI systems, agency is distributed across a network of influences – tools, collaborators, environments, data sets, and cultural histories – all of which shape and inform the outcomes.

Indeterminacy

In AI systems, latent space functions as a zone of indeterminacy because it does not represent stable entities, but rather fluid potentialities that are in a state of continuous transformation. Indeed, the inherent statistical logic is such that the level of stochasticity involved means that output remains partially unpredictable. Rather than being seen as a limitation, these grey zones resonate with artistic research, where the unknowable is not an obstacle, but an essential condition. In this context, uncertainty becomes a productive force – an open field in which new connections, meanings and insights can emerge without being predetermined.

Contingency

Artistic research embraces the idea of provisionality in creation, which is shaped by shifting contexts and is constantly evolving. This understanding is influenced by a variety of factors, including the characteristics of the tools employed, the specific requirements of the research and the inherently transdisciplinary nature of the practitioners, who frequently traverse disciplinary, cultural, and methodological boundaries. This contingency also characterizes the user interaction with latent spaces. In the case of large language models (LLMs), for example, meaning and output are not predetermined but continually shaped by prompting. The nature of this action varies depending on the user, the language employed, and the cultural or cognitive frameworks they bring into play.

The five aspects outlined above can be understood as archetypal methodological forms that converge for both artistic research and the AI functioning. As archetypes, they do not prescribe fixed models but rather shape the preconditions for exploration – pre-analytical orientations that nourish and guide the research process. In both domains, these five archetypal dimensions suggest the presence of operative latent spaces – one embedded in artistic research and creation, the other in AI models – each generating forms of knowledge that resist full predetermination.

While these symmetries offer a metaphor for the dynamic, associative, and open-ended nature of artistic inquiry, they also invite critical reflection on how AI logic clashes with the epistemologies of embodied and material knowledge-making proper to artistic research. On one hand, the metaphor of latent space offers a valuable lens through which to understand the non-linear, associative, and contingent dynamics of artistic research; on the other, it encounters a limitation in its inability to mirror the subjective, intuitive and practical dimensions of that research. Machine learning models can create new artworks with characteristics from their training data. It is a mere mathematical operation: the algorithm has no grounding in human life experience and subjectivity.43 In the latent space of AI, potential outputs are devoid of situated points of view, embodied experience, or contextual grounding. For these reasons, the research paradigms represented by latent space function not only as a useful metaphor for artist research methodologies, but also as a critical instrument for interrogating the boundaries, tensions, and specificities of artistic research when compared to the AI generative systems. Jeroen Boomgaard provocatively uses the figure of the Chimera – a mythical creature composed of incongruous parts – as a metaphor for the hybrid nature of artistic research methods, which resist fixed definitions and challenge the conventions of academic validation.44 The image of the chimera powerfully captures the utopian and ultimately unattainable dream of defining the methodological pluralism and richness that characterize artistic research. This plurality is inexhaustible precisely because it is in constant evolution – shifting between practice and theory, traversing disciplinary boundaries, and oscillating between the objectivity of inquiry and the subjectivity of the artist. In this regard, the notion of latent space as a methodological archetype further confirms the elusive and chimeric nature of artistic research. It can be understood as a partial and complementary lens that sheds light on the heuristic aspects of artistic enquiry without attempting to exhaust or fully define its inherent complexity.

Conclusion

Speaking of artistic research as a latent space acknowledges the invisible, emergent and often untranslatable logic underlying knowledge production. From this perspective, the metaphor of latent space, borrowed from artificial intelligence, functions as a conceptual tool for articulating the complex interplay of associative reasoning and iterative exploration that characterizes artistic modes of enquiry. Latent space becomes a way to address the processes by which new meanings emerge. The °’°Kobi platform, designed to enhance artistic research through associative navigation within a dynamic knowledge environment, offers a concrete example of how the notion, and structure, of AI latent space can be used as an operative epistemological tool.

By examining the °’°Kobi platform, we have seen how latent space can serve as a research modality grounded in emergence and contingency. °’°Kobi’s latent space functioning as an evolving reservoir of knowledge, where ideas are fluid and not yet tied to form, encourages the emergence of unforeseen connections, reflects some aspects of the modus operandi of artistic research. It mirrors the open-ended logic of the artistic inquiry mode of thinking that resists closure and enables artists to drift across conceptual domains, recombine influences, and reconfigure meanings.

The parallels between AI latent space and artistic research can be articulated through five central tenets – non-linearity, combinatory logic, distributed agency, indeterminacy, and contingency – which outline latent space as a methodological archetype within artistic research. Its legitimacy as a paradigm beyond AI is supported by the fact that the concept of latent space remains analytically productive when applied to artistic practices that predate both digital technologies and contemporary theories of creativity in cognitive science. As illustrated by several historical examples, the principles underlying the notion of latent space are deeply rooted in artistic traditions – ranging from the procedural randomness of Dadaism to the parodic logic of Pataphysics, from Brian Eno’s concept of creativity as a collective matrix to early theories of creativity grounded in associative processes.

The affinities between latent space and artistic research across the five core dimensions discussed above suggest the possibility of conceptualizing artistic research as a latent space ante litteram, aligning with the approach that views AI not merely as a technological innovation but as a tool for elucidating pre-existing paradigms. This perspective invites us to consider AI as a mirror, opening a reflection on how AI can contribute to fostering awareness.45

In conclusion, artists are navigators of uncertain and indeterminate knowledge territories, they work as dowsers of their own latent space of knowledge. Like skilled practitioners of an approach that is both intuitive and methodical, artists traverse complex terrains where knowledge is not always visible, but sensed, re-assembled, and revealed.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the project Enacting Artistic Research (EAR), funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU, Mission 4 Component 1, CUP B83C24001590005. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

+++

Veronica Di Geronimo

holds a PhD in Art Theory. She is currently a researcher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome working on new technologies in artistic research. Her professional experience includes both research and curatorial practice.

veronicadigeronimo@hotmail.com

Andrea Guidi

is a researcher in computational creativity and human-machine interaction, holding a PhD in Media and Arts Technology from Queen Mary University of London. A musician and artist, they have performed and exhibited at major multimedia art festivals, including Ars Electronica (Linz, Austria).

Noten

- Andersen, Ian. “Starting Point.” The Age of Data: Embracing Algorithms in Art & Design, ed. by Christoph Grünberger, Niggli, 2022, p. 6. ↩

- Eugeni, Ruggero, and Roberto Diodato. “L’immagine algoritmica: Abbozzo di un lessico.” La Valle Dell’Eden, no. 41-42, 2023, pp. 5-21, ojs.unito.it/index.php/vde/article/view/10819/8893. ↩

- Hinton, Geoffrey E., and Ruslan R. Salakhutdinov. “Reducing the Dimensionality of Data with Neural Networks.” Science, vol. 313, no. 5786, 2006, pp. 504-07. ↩

- Goodfellow, Ian, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016. ↩

- Kingma, Diederik P., and Max Welling. “Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes.” ArXiv.org, 20 Dec. 2013, arxiv.org/abs/1312.6114. ↩

- Somaini, Antonio. “Théorie des espace latentes.” Le monde selon l’IA, JBE Books, 2025, p. 22. ↩

- Voto, Cristina. “Verso una semiotica della spazialità latente.” Il volto latente, ed. by Massimo Leone, 2023, pp. 222-37. ↩

- Loh, Bryan. “Creativity as Search: Mapping Latent Space.” Runway, 2 Dec. 2024, runwayml.com/research/creativity-as-search-mapping-latent-space. Accessed 11 July 2025. ↩

- Yee-King, Matthew. “Latent Spaces: A Creative Approach.” Springer Series on Cultural Computing, Springer Science+Business Media, Jan. 2022, pp. 137-54, doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10960-7_8. Accessed 10 Nov. 2024; Bryan-Kinns, Nick, et al. “Exploring XAI for the Arts: Explaining Latent Space in Generative Music.” ArXiv.org, 10 Aug. 2023, arxiv.org/abs/2308.05496. Accessed 18 Oct. 2023. ↩

- Tahiroğlu, Koray, and Wyse Lonce. “Latent Spaces as Platforms for Sonic Creativity.” Conference: International Conference on Computational Creativity, ICCC ’24, 2024. ↩

- Borgdorff, Henk. The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden University Press, 2012. ↩

- Leavy, Patricia. Method Meets Arts: Arts-Based Research Practice. Guilford, 2020; Rolling, James Haywood Jr. “Artistic Method in Research as a Flexible Architecture for Theory-Building.” International Review of Qualitative Research, vol. 7, no. 2, Aug. 2014, pp. 161-68, doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2014.7.2.161. Accessed 5 Dec. 2019. ↩

- Hannula, Mika, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén. Artistic Research: Theories, Methods and Practices. Helsinki Academy of Fine Arts, 2005, p. 160. ↩

- Borgdorff, Conflict of the Faculties, p. 124. ↩

- Biggs, Michael, et al. The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts. Routledge, 2011, p. 57. ↩

- Borgdorff, Conflict of the Faculties, p. 124. ↩

- Haseman, Brad. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, vol. 118, no. 1, Feb. 2006, pp. 98-106, doi.org/10.1177/1329878x0611800113. ↩

- Feyerabend, Paul. Against Method. Verso, 1975. ↩

- Sbrilli, Antonella. Storia Dell’arte in Codice Binario. Guerini e Associati, 2001, p. 215. ↩

- Bok, Christian. Pataphysics: The Poetics of an Imaginary Science. Northwestern University Press, 2002. ↩

- Hugill, Andrew, et al. “The Pataphysics of Creativity: Developing a Tool for Creative Search.” Digital Creativity, vol. 24, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 237-51, doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2013.813377. Accessed 4 Apr. 2019. ↩

- Boden, Margaret A. The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms. Routledge, 2004, p. 3. ↩

- Montuori, Alfonso, and Gabrielle Donnelly. “Creativity and the Future.” Encyclopedia of Creativity, 3rd ed., Elsevier, Academic Press, 2020, pp. 250-57. ↩

- Bridle, James. “Is Creativity Over?” WePresent, 20 Feb. 2023, wepresent.wetransfer.com/stories/james-bridle-on-creativity-and-ai-collaboration. ↩

- Eno, Brian. “Lecture: Brian Eno.” Red Bull Music Academy, 2013, www.redbullmusicacademy.com/lectures/brian-eno. ↩

- Poincaré, Henri. Science and Method. Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1914, pp. 50-53. wellcomecollection.org/works/e6hus9k4. Accessed 13 Mar. 2025. ↩

- Wallas, Graham. The Art of Thought. Butler & Tanner, 1926. ↩

- Mednick, Sarnoff. “The Associative Basis of the Creative Process.” Psychological Review, vol. 69, no. 3, 1962, pp. 220-32, doi.org/10.1037/h0048850. ↩

- Boden, Margaret A. “Computer Models of Creativity.” AI Magazine, vol. 30, no. 3, July 2009, p. 23, doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v30i3.2254. ↩

- Basualdo, Carlos, et al. William Kentridge: Triumphs and Laments. Walther König, 2017, p. 50. ↩

- Chen, Zhen, et al. Chen Zhen: Short-Circuits. Milan, Skira Editore, 2020. ↩

- Bryan-Kinns et al. ↩

- Watanabe, Shingo, et al. “Human-In-The-Loop Latent Space Learning for Biblio-Record-Based Literature Management.” International Journal on Digital Libraries, vol. 25, no. 1, Springer Science+Business Media, Jan. 2024, pp. 123-36, doi.org/10.1007/s00799-023-00389-8. Accessed 25 May 2025. ↩

- Szoniecky, Samuel, and Nasreddine Bouhaï. Collective Intelligence and Digital Archives. ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, 2017. ↩

- Coessens, Kathleen, et al. The Artistic Turn: A Manifesto. Orpheus Instituut, Leuven, 2009, p. 65. ↩

- Guidi, Andrea, et al. “Enhancing Artistic Education with AI: Tracking Creative Behaviour in Higher Arts Education.” Teaching and Learning in the Generative Artificial Intelligence Age, ed. by Demetrios G. Sampson et al., Springer, forthcoming; Giretti, Alberto, et al. “Knowledge Engagement in Art and Design Education: About the Role of AI in Creativity Education.” Cognition and Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age, ed. by Pedro Isaias, Demetrios G. Sampson, and Dirk Ifenthaler, Springer International Publishing, Jan. 2024, pp. 3-24, doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-66462-5_1; Ripa di Meana, Franco, et al. “°’°KOBI: A Knowledge Ecosystem for Research and Education.” AI, Cultural Heritage, and Art between Research and Creativity, 2024. ↩

- Runco, Mark A., and Selcuk Acar. “Divergent Thinking as an Indicator of Creative Potential.” Creativity Research Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 66-75. ↩

- Giretti et al. ↩

- Barale, Alice. Arte e intelligenza artificiale: Be my GAN. Jaca Book, 2020, pp. 103-09. ↩

- Koubová, Alice. Artistic Research: Quest for Method. Academy of Performing Arts Prague, 2017, p. 9. ↩

- Borgdorff, Henk. “The Production of Knowledge in Artistic Research.” The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, ed. by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson, Routledge, 2011, pp. 44-63. ↩

- Bridle. ↩

- Chollet, François. Deep Learning with Python. Manning Publications, 2017, p. 365. ↩

- Boomgaard, Jeroen. “The chimera of method.” See It Again, Say It Again, ed. by Janneke Wesseling, Valiz, 2011, pp. 57-71. ↩

- D’Isa, Francesco. La Rivoluzione Algoritmica: Arte E Intelligenza Artificiale. Luca Sossella Editore, 2024. ↩