Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 30 nr. 1 | 2, pp. 68-79

Broken View. Belgisch-Congo en de magische lantaarn

Hannes Verhoustraete

As an early projection device, the magic lantern was often used for colonial propaganda. For instance, to showcase and legitimize the ‘good works’ of the church in the colony. But lanterns were also used by missionaries in Africa to evangelize the local people and create a colonized mindset. This text is a reflection on the work process of Broken View, an essay film on colonial images from the Belgian Congo and the magic lantern. Through montage, collage, and assemblage the film examines and recontextualizes these images of the Belgian colonial past.

Als vroeg projectiemedium werd de toverlantaarn vaak gebruikt voor koloniale propaganda. Bijvoorbeeld om de 'goede werken' van de kerk in de kolonie te presenteren en te legitimeren. Maar lantaarns werden ook door missionarissen in Afrika gebruikt om de plaatselijke bevolking te evangeliseren en een gekoloniseerde mentaliteit te creëren. Deze tekst is een reflectie op het werkproces van Broken View, een essayfilm over de toverlantaarn en koloniale beelden uit Belgisch-Congo. Door montage, collage en assemblage onderzoekt en hercontextualiseert de film deze beelden uit het Belgische koloniale verleden.

In 1908 the Belgian State annexed King Leopold’s Congo Free State under international pressure following campaigns against the institutionalized cruelty and plunder of the Congo. But Leopold’s voracious imperialist mindset was not widely shared in Belgium and in contrast to the British or the French, the average Belgian’s imperial mind always remained rather low-key.1 Although the historical theme of reluctance rings true, it is nevertheless an ambiguous one, in which one could find ways of retrospectively disavowing responsibility. To have been a reluctant colonizer could make it easier to insinuate that we made the best of a tainted heritage and that all the bad things are in fact remnants of this forced heritage about which we can only do so much. Leopold, large-looming figure as he was, became as much an object posthumously venerated for his génie as well as a phantasmagorical apparition behind which one could hide one’s own colonial politics and responsibility.

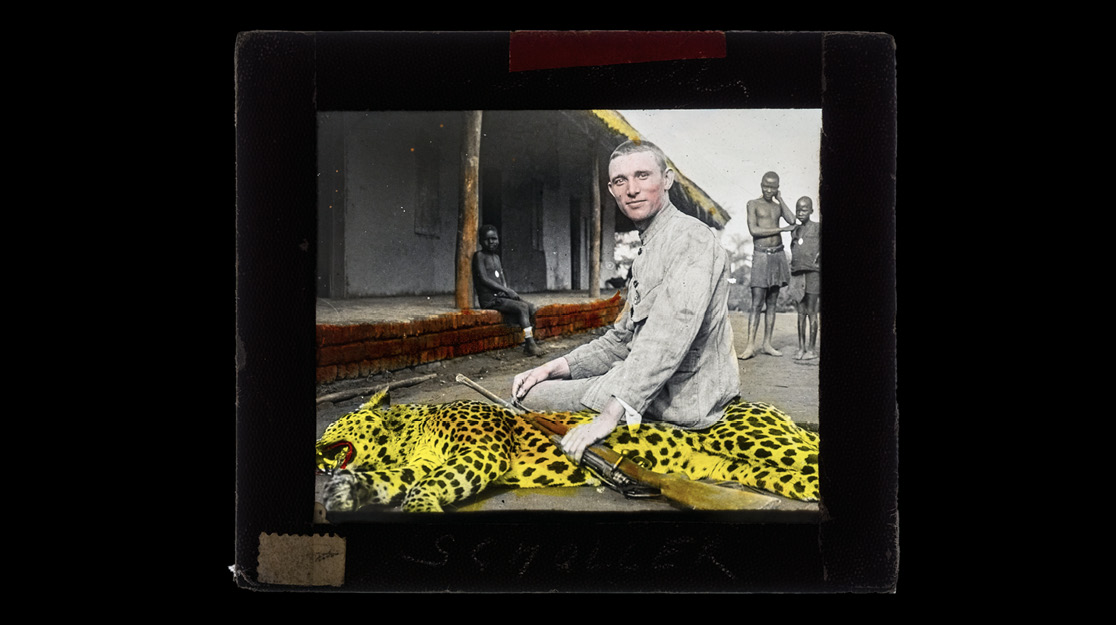

In this text I will reflect on the film I am currently finishing, Broken View, a feature-length essay film on colonial images of the Belgian Congo. Because the film is not finished at this time of writing, I will attempt to capture the filmmaking process in medias res. Broken View is made within the context of the B-magic joint research project on the history of the magic lantern in Belgium. It takes as a starting point glass slides of colonial photographs from the Belgian Congo, from both clerical, secular, and state sources, which are now kept in various archives.2 These images of the colony were projected with magic lanterns in parishes and other social venues ranging from opera houses and small theatres to local guilds, political rallies, schools, social clubs, philanthropic societies, scientific lectures, and fairgrounds throughout Belgium in the first decades of the twentieth century. The projections were part of the propaganda effort to sell the Congo3 to the Belgian public, which was somewhat reluctant or unenthusiastic towards the colonial project.

A means to many ends

Belgium had little prior colonial experience and Belgians knew next to nothing of the country theirs had just colonized. Like all colonial powers, it tried to conjure up the colonial spirit through propaganda. One of the numerous ways in which this endeavour was undertaken, was the magic lantern show: photographic and illustrated images projected in the dark and accompanied by a lecture.

In the film, I discuss the history of the lantern, the invention of which in the seventeenth century is commonly attributed to Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695). It was further optimized in the following centuries to become a mass medium in the nineteenth century.4 The lantern was used for many purposes. As the voice-over track of the film goes:

It covered a wide range of subjects; diabolic, grotesque, erotic and pornographic, scatological, religious, historical, scientific, political, and satirical. […] It was used by entertainers and quacks, scientists and clerics, salesmen, pedagogues, and demagogues. Its light shone in public venues, the salons of aristocrats and the bourgeoisie, and travelling lanternists called Savoyards entertained the common people in the streets and in their homes. All equally in thrall, all ever more demanding.

In the colonial context, magic lantern projections were part of a two-way propaganda effort. The lantern was used in Europe to showcase the good works of the church, state, and industry, to mould a popular colonial mindset. In the case of the catholic missions, it helped to raise support, procure funding, and convince young men and women to join the mission civilatrice. But the magic lantern was also used by missionaries in the African continent and elsewhere in the non-Western world in educating and evangelizing people. Although research on the use of the lantern in Belgian Congo is still ongoing (see the work of De Weerdt in the framework of B-Magic), the practice in other parts of colonial Africa has been well documented.5 As Catholics in Belgium made ample use of the lantern for propagandistic, educational, and catechumenal purposes,6 it seems unlikely they would have refrained from employing this efficient device in Congo.

Since the intended effect would have been different, what was shown to Belgians and what was shown to the Congolese population would have differed a great deal. Where the shows in Belgium were intended to spark a popular colonial mindset, in Congo they would have been used to teach a largely illiterate indigenous population (for the most part intentionally kept this way) about Christ’s suffering for their sins, instil in them the fear of God, and teach them how life was supposed to be lived. In other words, it would have helped in cultivating a colonized mindset. Lanterns were effective tools in what the missions set out to accomplish: ‘The conversion of African minds and space’.7 To uninitiated viewers, the lantern itself, this seemingly complicated piece of technology, attributed a great deal to the spectacle and proved a most effective means of capturing their attention.

The film starts out with a well-known anecdote from the missionary David Livingstone’s memoirs in which he recounts the reaction of the Balonda people to the projection of an image of a biblical scene: Abraham about to sacrifice his son Isaac. When he moved the slide, the Balonda thought Abraham’s knife was coming towards them instead of Isaac and ran off scared – according to Livingstone at least. Afterwards, Livingstone made sure to demonstrate the workings of the lantern so that no one would ‘think there was anything supernatural in it’.8 This use of knowledge of the natural world, of technology, to convert people to another supernatural order, to Christianity, is a central focus of the film. In the commentary, I paraphrase Adorno and Horkheimer: ‘Enlightenment reverts to myth.’9

Essayer

When first confronted with these colonial lantern slides, I found myself affected in three ways. First by the violations and hubris the images bared testimony to, and the way in which I felt I was seeing them for the first time, while at the same time they seemed all too familiar. Second, by the quality of the often lavishly hand-painted slides – what a time-consuming business it must have been – that creates a tension between aesthetic experience and historical consciousness. And third, by the vast quantities of them that have survived.10 Initially, I limited myself to the archive of KADOC Documentation and Research Centre on Religion Culture and Society in Leuven. But soon, I found that tropes from mission photography spilled over in other instances of colonial propaganda images, so I included, lacking perhaps a rigorous method or a plausible reason, images from other secular archives in the film. I chose not to identify these different sources at the specific moments they appear. I wanted to find a way to translate this sensation of facing a mountain of images – at once too many and never enough – and the near impossible venture of making sense of them, at least to me. ‘An endless procession of real ghosts’, is an image I recall crossing my mind during these first visits to the archive in Leuven.

As the film is mostly comprised of archive material, I was looking for a way to convey the element of chance that I cherish in documentary cinema, the mediation of contact with a specific piece of reality, traces of time spent, of capturing a specific moment and not another, of my wonder at the glass objects, their weight, texture, fragility, and durability. In short, I sought to include in the film the phenomenology of the archive and how this tangibility and my sensorial experiences related to the reality of the ghosts in the pictures.

I could well have made a very different selection of images than I ultimately did. The work in the archive and the textual research did not precede the actual composing of the film. To mark a beginning, I felt I had to start putting images and words together from the get-go, seeing montage not as a final stage of the filmmaking process, but rather as a way of beginning, montage as a way of writing. My plans, ideas and poetics went through many permutations. I approached the archival work and research from my own perspective, which differs greatly from the methods of trained historians, that is (I dare hardly say), from an intuitive basis. It might seem disrespectful to the material, to the weight of what the images represent, to approach them intuitively, play with them almost. But play does not equal light-heartedness or carelessness. Here, it was more a question of attuning to the physical material as well as to the historical matter of the colonial past and its echoes, in a tentative, essayistic way.

I see montage not as a final stage of the filmmaking process, but rather as a way of beginning, montage as a way of writing.

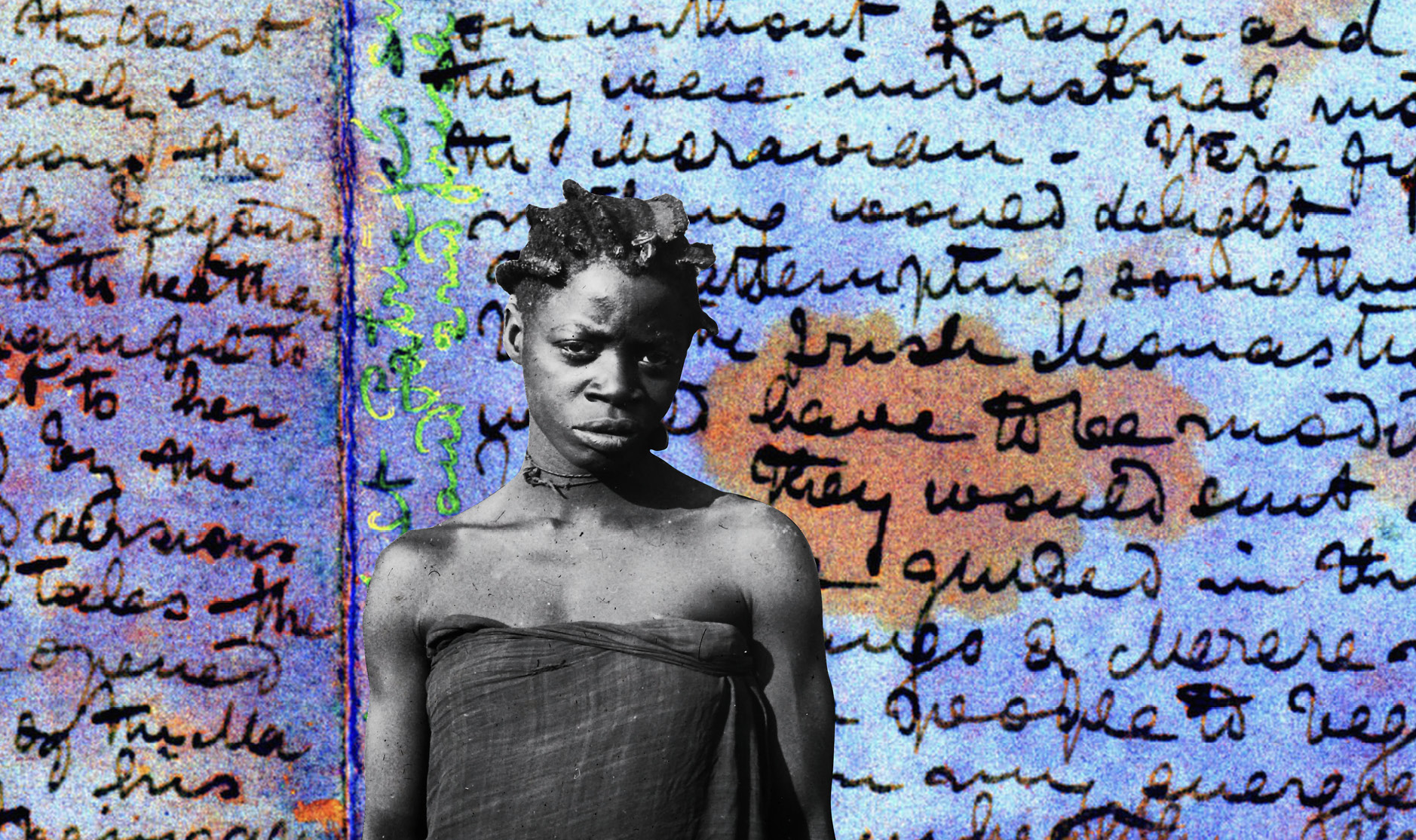

In trying to find a way to present still images in a medium which relies on movement, I quite intuitively turned towards collage. This way, movement lies in the act of cutting out, in the tension between two arrested movements: the captured ça a été of the photograph and the completed collage-gesture that brings two or more images in the same space. The form gives rhythm to the discourse and engenders it. The cutting out of figures becomes a formal translation of what I try to do in the film discursively, to decontextualize and recontextualize fragments from the past. It performs the question of how to see these colonial images today, if we even should see them?

Perhaps the only way to be able to show these images is when they are set in motion within a poetic space that aims to do justice to the realities of oppression from which they were taken. I am aware that some of the images in the film are hurtful to see. I am aware that some will see the reuse of these images as a continuation of the violence their taking involved, and that my position as a white European man will enforce this view. Though I have seen instances of this reiteration of colonial violence in cultural products that purport to denounce the colonial past, I do not believe that to show these images, even violent ones, even from my side of the colonial heritage, automatically implies continuing the violence they both document and materialize. I think this happens when not only the images themselves but also the spectacle-form and ideological framework in which they were presented are reproduced, in other words, when the effects of their reproduction are either ignored or anticipated and exploited in the service of this or that agenda. I have not treated this lightly. Broken View does not seek out a shock effect, it does not try to sell a product or resort to cynically rousing controversy to gain attention in an increasingly saturated audio-visual market. Nor do I claim a sort of neutral ground or moral high ground. It is the spectacle-form, the milieu in which these images were made and shown, that I hope the film interrogates and deconstructs. I do this knowing that any deconstruction is also a construction, that my film is also a form, and that there is no inherently unproblematic form.

Both the essayistic montage and the collage, the poetics I turned to in this film, bring together elements that often have little to do with one another. They do this, as the writer Brian Dillon wrote about the essay form, ‘in such a way that the scandal or shock of their proximity arrives alongside a conviction that they have always belonged together’.11 So, these images must be accompanied by other images, brought into relation with other, maybe even seemingly unconnected images. These relationships are not comparisons or equations, but the threads of an unfinished fabric, a continuous work of de- and reassembly, a broader, perhaps speculative contextualization. Assemblages are formed in which the figures are brought into each other’s orbit, within a wider frame and into another timeline than those of the photographs they were taken out of, inserting them into new constellations, trying to find new rhythms. In doing so, I hope to make visible some of the brushstrokes with which they were originally made, the power relations these images texturized and helped (helplessly) to fabulate, the purposes they were to serve. The film is an essay, an atlas of sorts, or an album where fragments of images and language exchange their shortcomings,12 what words can show and what images can say.

But what to say? Who is speaking and to whom? The spoken text is not only a feature of the essay film. Magic lantern projections were almost always accompanied by live narration. In the case of mission photography almost always in the explanatory mode, an authoritative register, a man, a priest, who spoke with full authority on what was being projected. There was no doubt in his voice. There is but one truth, and that is the Christian truth. At this stage in the editing process, I am trying to find a balance between different registers of the voice-over. The challenge is to subvert the authority of the colonial voice, to replace it not with silence, but to find another way of speaking, of giving information, to introduce an element of doubt. This can reside in subtle formal gestures, a tone of voice, an emphasis turning into a question mark, repetition, or wordplay. I am not quite sure yet how, but I want to let this informative, authoritative mode disintegrate into a poetic mode. I mean poetry in the sense that it is the opposite of the direct speech of the colonizer. That it is a tentative way of speaking. An essayistic way of speaking if you will. The text becomes a collage of registers, of sources and tones but spoken by a single voice.

Phantasmagoria and fetishism

Livingstone’s anecdote finds an echo in the fear that the lantern stirred in the Paris bourgeoisie just after the French revolution, when Étienne-Gaspard Robert, famous under the stage name of Robertson, scared the wits out of them with his eerie projections of devils and ghosts in his phantasmagoria.13 A popular hoax at the first demonstration of the cinematograph a century later, in like manner claimed that people ran away from the image of a train coming towards them. So, this kind of fearful reaction, no doubt exaggerated, was in no way particular to African viewers, as racist theories of the age held, and as Livingstone seems to insinuate in his writings. This inflated representation of Africans’ awe at Europe’s display of its technological and so-called moral superiority was a way of tempering Europe’s fear of the African, of a Black uprising, the fear that the Other was in fact quite similar. After all, all you had to do was light a lamp and they would fear you or come to worship you.14

The representations of fearful reactions to technology of both the Balonda people and the Paris bourgeoisie are recurring motifs. And the demonstration or performance of technology as a colonial or civilizing tactic is central to the media-archaeological undercurrent of the film. To better understand the images of the colonial past, it is necessary to look at the technology involved in their production and projection. It is, then, curious to notice that the colonial spectacle seemed to rely on both the dissimulation and the demonstration of its technique. It seems that for Livingstone the demonstration of the technique, the deconstruction of his spectacle was an integral part of that spectacle. But for Robertson, the disguising of his sorcery was a constant principle. Being in the dark about how it worked was crucial, although many spectators knew the ghostly apparitions were probably not the work of the devil. In both cases, the ambiguity of images – evident uncanniness, uncanny evidence – spills over onto the image-machine. Livingstone’s demonstration does not seem to threaten its reception as a magical device. Robertson’s concealment of the machine provokes even more curiosity and speculation as to how it could function, relying on a carefully composed and exploited tension between the phenomena of myths and the promise of technological progress. In some cases, the cause (evangelization) is most helped by revealing something, in others, the cause (making money) might best be advanced by hiding it. In both instances the fetishistic effect remains; something always remains hidden, if not the origins and mechanisms of the object, then the intended (long-term) effects of its functioning.

The colonial project was not a homogenous system rolled out evenly and rationally, but rather messily to some extent. The spectacle, to which the magic lantern projections at home contributed, surely dissimulated this uneven, chaotic aspect of the colonial project. More important than control, after all, is the semblance of control. To the average Belgian viewer in the audience, it must have seemed as if everything was functioning smoothly. Whether she believed this, is another matter I have not been able to ascertain beyond speculation. Conversely, the demonstration of Western technology, the smooth functioning and apparent efficacy of tools, could give an African viewer the impression that not only this particular tool was under the white man’s total control, but possibly anything. The demonstration of one amazing capacity serves to disguise the demonstrator’s human limitations in many others, along with any indication of his own similarity (unless of course this similarity serves a purpose).

Mirrors were among the objects that were used to impress people in the early days of contact between European travellers and African trading partners. They were common enough objects to Europeans but in high demand in Africa. They had greater manoeuvrability than the metal reflectors and water surfaces that were used by the Africans. When missionaries set out to evangelize Central Africa in the nineteenth century, mirrors had been circulating there for centuries and had become an integral part of many religious practices. They were a portal between the visible and invisible world. They were used for divination, initiation, and protection. They could be used to reveal both ancestors and witches, to reveal the hidden forces at work in society. In short, they were dangerous ambiguous objects pointing to the perils of the soul. In extension, the same could be said about photography, as in Congo and Gabon, the photographic negative is called diable, or devil.15

Not only in Africa did people believe that photographs could capture the souls of people or reveal the ghosts of ancestors or witches. In the late nineteenth century, Europeans were avid consumers of the occult. Dr. Hippolyt Baraduc, for example, claimed to have found a process by which he could capture the human soul on the photographic plate.

He claimed ‘a vital cosmic force saturates the organism of living beings and constitutes our fluidic body. […] We all live in a sea that we cannot see.’16 He argued that it was possible to make an image of this fluidic invisible with instruments more precise than the human eye. Enter photography. ‘Nested in double negatives, we find a material vision of God. […] Immersed in a fluidic invisible, of which we are both the container and contained, we float in the amniotic liquid of divinity.’17

To convince himself of his difference, his superiority, his belief that there was no better way to live than his, that beyond Christianity there was no other valid spirituality and cosmogony, the colonial mind has had to ignore many signs of the contrary. In an essay on fetishism, the late anthropologist David Graeber, argues that this could not have been an entirely unconscious process. He describes a moment in history where early Portuguese traders’ confrontations with the ways of life of their African trading partners must have ‘cast doubt about these early travellers’ existing assumptions about the nature of the world and of society’.18 In witnessing what seemed arbitrary customs and conventions regarding the logic of government, economic value, sexual attraction, etc., they could hardly have remained solidly convinced, Graeber argues, that their own ways were not as arbitrary as those of the people they encountered.

By describing Africans as ‘fetishists’, they were trying to avoid some of the most disturbing implications of their own experience. […] It was not the ‘Otherness’ of the West Africans that ultimately drove Europeans to such extreme caricatures, then, but rather, the threat of similarity – which required the most radical rejection.19

This radical rejection of similarity, of the unbearable truth that truths are relative, sparked a further proliferation of phantasma. Photography and by extension to some degree the magic lantern, played an at once obvious and ambiguous role in this bi-directional colonial phantasmagoria, in which, according to the anthropologist Joseph Tonda ‘the phantasma of the colonizer and the colonized diverge and converge around the produced image.’20 In a remarkable passage of his Le souveraine moderne, he describes the colonial civilizing project as

An immense photographic apparatus producing negatives, devils, monsters or contemporary ghosts in Africa. […] The development of these negatives or these devils should be understood as the development of which the African and Western states are the supposed artisans. It consists concretely in transforming the African devils produced by the devices of the civilizing mission in évolués or developed Christians and citizens. The developed, like the civilized and the devils, are all phantasmas of the developers and the civilized, in the same way a photograph is a phantasma of both the photographer and the one who is photographed. The indigènes, the savages, the primitives, like the evolués, the civilized or the developed are elements of the same structure of the fetishism of the modern Sovereign.21

Smiling faces

Another axis of the film lies in the tension between two kinds of archives, two kinds of uses of the photographic image. The public or institutional archive on the one hand and the private or personal archive on the other. I was particularly interested in the echoes of these glass slide images that I found in the personal 8mm archives of an uncle who had served as a medical assistant in the Belgian Congo in the 1950s. The way he filmed his future memories, how he filmed the colonial other, resembles in many ways the codes and poetics of mission photography of the first half of the twentieth century. I couldn’t help but detect an aesthetic relation between his images and the ones from before his time. I saw similarities in the way he asked people to pose, his choices of what to film, the kind of scenery that he captured and how. There are also traces of the visual grammar of other popular ethnographic material, especially images objectifying and sexualizing African women. It was too late to ask him, but it seemed to me that as a child or as a young man he must have seen these propagandistic lantern projections and, consciously or not, incorporated the poetics of mission photographs into his own personal memory production, his filming practices. Perhaps he was not only trying to document his own time there and his family growing up, but also recreating an image of Africa he had seen before, trying to match his own time with what was in the fifties still an image from a fairly recent past, his experience of Africa to an imaginary one, staging his adventure in the visual grammar of the so-called colonial pioneers, aligning his own gaze with theirs and the worldview propagated in the bulk of popular cultural production aimed at the adventurous youth of the first half of his century. Many of the images are of hunting parties, boat rides, idyllic family scenes, orchestrated rituals and dances performed by indigènes and catholic processions of Christianized Congolese people. He stages his own colonial self, a fantasy, according to well-established tropes, he creates an identity, for himself, for his later self, and the select group of intimates that would eventually view these images back home. It seemed to me that, at least to some extent, colonial propaganda had succeeded in moulding his colonial mindset, at least in the ways everything was made to appear.

There is of course no way of making a clear distinction between private and public uses of the photographic image. The personal and the public are intertwined and complicate each other. Making images of one’s own life is always done against the backdrop of images of the lives of others, a public image of private life surging from deep down the trenches of ideology. In my uncle’s images I saw traces of the formal codes of official colonial photography (and cinema). But in the glass slides of mission photographs, the ones depicting the white colonials themselves, I also caught glimpses of personal lives being lived that reminded me of my uncle’s 8mm films. Behind the veneer of moral duty, you can see young people, missionaries, nuns, engineers, soldiers, doctors, and wives appearing as having the time of their life. I understand that making this observation could easily be understood as romanticizing a period which obviously needn’t be, or as relativizing the petty individual colonial’s involvement à la ‘O, they meant so well’. But recognizing a smile does not automatically invite me to smile back. I think it is crucial to address this happiness and sense of freedom, of power, because it attests to how the individual colonial projected him- or herself in the colonial idea, then and retrospectively. When I first heard of the Congo in my childhood, it was in this melancholic, paradise lost kind of register, which through the years I experienced with growing unease, frustration, anger. This projecting went on until my uncle’s death, in revisiting images, in repeating commonplaces coated in toxic nostalgia and the regalia of persistent myths. I think a rejection of this emotional aspect of the colonial mindset would be a mistake because it is at least part of how it is transmitted to next generations, however unconsciously and however subtly. Again, to recognize affects as meaningful is not the same as sharing them, empathizing, or even identifying with them, nor as asking anyone to consider them, care about them, or see their authenticity as a mitigating circumstance.

I see the smile here as the marker of a successful ideology. A smile that could be smiled, if not always directly at the expense of the Congolese people, then in spite of their oppression and suffering, in spite of the ‘bloody catalogue of oppression’.22 It goes without saying that these smiling white faces are in stark contrast to the many other black faces in colonial photographs that have very little to smile about. But it is just this contrast which reveals the frightening dynamic range of the human being, capable of creating spaces where smiling and suffering faces can co-exist as if it’s nothing at all, indifferently, undramatically, banal. I think it’s important to keep an eye on this smiling face, because I know that it hides another. In the film I ask, ‘Where does a smile go after it’s smiled?’

‘The fog in my head’

The tensions between public and private, colonizer and colonized, phantasma and human being that I have been trying to describe are the main orientation points in the editing process. As I mentioned, I see montage as more than the assembly of an executed scenario or concept; rather as a continuous essayistic writing process. Somehow it is impossible for me to stick with one thing. Rather than getting to the bottom of one thought, I seem to always need to bring it into relation with another. This makes that Broken View is also about the materiality of the glass, the 8mm film, of paper, of memories, in short, the phenomenology of the archive, of traces. About enlightenment reverting to myth. About living in a sea that we cannot see. About the birth and use of technologies that always occur within an existing web of power relations. About fear. It’s about rituals. The idea of the fetish as a god under construction. About social creativity. About phantasmagoria, the occult, hot air balloons and the view from above, about maps. About the suspension of disbelief. About mirrors, paintings, and books. It’s an assemblage of archival materials, a composition about composition. And doing this as a non-expert in any of the fields I touch, bearing in mind something I think the Dutch filmmaker Johan van der Keuken said about the filmmaker being a person who knows a little about a lot of things, as opposed to the figure of the scholar or the scientist who knows a lot about one particular thing.23

But I am no polymath.

I often don’t know what I’m doing. And it’s easy to succumb to the chaos, to anxiously wonder where it is all leading, whether the association of ideas that you’re trying to present is not a bit of a stretch, whether your research is not too superficial. Whether you’re utterly and bitterly wrong. At those moments, I generally spiral towards a crisis and end up stopping for a while. But during the work on this film, I found another way of remedying or staving off this stasis.

The film is an essay, an atlas of sorts, or an album where fragments of images and language exchange their shortcomings, what words can show and what images can say.

The specific formal devices I use in this film allowed me – required me even – to dive off into the abyss of concrete work, into details, a specific line that needs attention or a tone of voice that needs finding. There is a lot of sometimes tedious archival work and photoshopping involved, cutting out figures, cleaning up images. In creative crisis I come to cherish tedium – although I wonder how some of the images that I use could ever sanction this feeling. Anxiety and boredom become the extreme ends of my emotional spectrum. I work on the sound for a while, to find a kind of musicality, forget about the overarching structure of the piece and focus on a phrase. I alternate between the point of view of the puzzler bent over the table and that of the improvising musician. As a filmmaker, I am incredibly envious of musicians and other performers and want sometimes for the immediacy and abstraction of their trade.

Another problem is the multitude of sapling ideas, some more (ir)relevant than others, that occur at bad timings and get you carried away. While this getting carried away is of course very fruitful at times, it is nevertheless difficult to find a middle ground between concentration and the trance-like state of streams of consciousness. More so if you have the bad habit of hardly ever reading your own notes. It’s as if saving them for some later date is enough to ease my mind for a while and keep working. The saving of the shadowy outlines of premature ideas becomes a kind of ritual to stave off anxiety about the project. Like keeping a dream log. I started using the subtitle tool in my editing software as a way of making notes, that way I would have them literally in the timeline, obstructing my view when necessary, reminding me and helping me along at other times. This way, montage literally becomes a way of writing.

The essays of Brian Dillon on essays encouraged me to attempt to write or work from this fog. He wrote:

The fog in my head began to propose itself as a way of thinking, where before it had felt precisely like not-thinking… I had always thought that my problem with writing was my lack of lucidity and energy, a failure or focus. Was it possible I could write out of the fog itself, out of confusion, disarray, debility? From inside the disaster itself?24

It was an important reminder that although it does not mean that anything goes, the essay form allows for freedom, of losing yourself in detail, getting carried away by a side-thought, only to emerge once again and from a bird’s view to try and map a way out of the maze. In reading Dillon, I felt free to alternate between researching and creating, between writing and editing, to let the stages of the production of a film completely collapse into one impossible movement.

The sea we cannot see

This movement between in medias res and the bird’s eye view is a central notion in my practice. To find myself in a double bind, and willingly so, between the immersion of the material and the oversight of the structure. Constant movement is required in order not to let the rhythm die out, petrify. In a completely different context, art historian Georges Didi-Huberman formulates a movement I associate with this way of working: ‘This movement is as much an approaching as a distancing: approach with reserve, distance with desire. It supposes contact, but it supposes it interrupted, if not broken, lost, impossible through and through.’25 This impossible movement could also be used to describe facing these colonial archives in our time. Also, here it is a question of interrupted, broken contact, an approaching and a distancing. There is no safe or definitive position from which to speak... or edit. They are ghosts now, colonizer and colonized. And yet, as ghosts, very much alive.

This tension between approaching and distancing characterizes not only the creative process of this film but has been a constitutive dynamic throughout my broader artistic research project on the essay form as a historiographic mode. It is through this frame that I have been trying to deal with the past. Between the immediacy of images and the mediation of the text, the stringing, tuning, and playing of my ‘instrument’ collapse into one dialectic activity.

Despite the enduring popularity of heroic, event-based, spectacular history production, it should go without saying that the past cannot be seen as a continuous ribbon of events leading up to my navel, and that there is no grand, all-encompassing historical project in which all the historians have decided to divide the labour and that eventually they will agree on some definitive version. This persistent notion of history has to do with the effective ways in which the past has been represented and mobilized in the past – with poetics and aesthetics – and is connected to an equally resolute notion of the story.

I love a good story but hate that it has become virtually synonymous with storytelling, especially in the audio-visual domain. The story writes itself. Within this stringent notion of narrativity the story becomes a bright open space in which everything is visible except the functionalities or poetics of the narrative. A story like so many contemporary interiors: safe, smooth, white, analeptic minimalism, cupboards without handles, invisible switches, lids, and faucets rid of the signature of their functionality.26 As much as we want stories to escape from our home lives, these stories, even of very far places and people, increasingly templated as they are on the ratio scale between the strange and the familiar, resemble more and more the structure of the spaces in which we view them. Spaces you can oversee in one ambient peek, uncomplicated yet profound, free of debris.

But I want stories to come home to as well, stories to leave home for. One way I imagine the story, and by extension history, is as the messy room described by the Dutch poet Bert Schierbeek in his long poem Weerwerk [Resistance], which has not been translated into English.

… and a bit later you go through the house

Looking for a book ‘Die Insel des Zweiten Gesichtes’

And you think of course it’s underneath something

Always the one is underneath the other

Indeed

One world is beneath the next

and each unaware of the other27

This is not a plea against artistic simplicity, clarity, or formal ascetism (or tidy living rooms), but rather against formatted, templated, structurally unimaginative modes of cultural production that anticipate their effects, make historiography appear as an exact science and history as a smooth timeline – not only as a continuous ribbon but as an unwrinkled one to boot. It is a poetics in which montage has been replaced by cross fades, dissolves, smooth transitions. To the essay and its scandalous play of proximity montage is essential. Where the dissolve securely closes off the interstices between the elements, the cut marks both transition and rupture. We are not being driven; we walk. The cut (and I understand this more broadly than only cinematographically) takes us from one space and time to another, steps over something that is left unseen, unheard, unsaid, left to be imagined. It is a door left ajar. The essay does not glue together or blend different worlds that have no awareness of each other, it composes them into configurations, assemblages, atlases, imaginary museums, a lacunary tapestry28 that is held together as much by its fibres as it is by the spaces between them.

Leaving traces of the process in the finished work, leaving spaces in between, some debris of the messy business of approaching and distancing, is perhaps a way of recalling that it is people who make images, who make idols and gods and write history, who create the mess and the map. With Broken View I try to approach the colonial past from the mist. It’s an attempt at rendering visible the sea we cannot see, not the material vision of God but the ideas that contain us and that we contain, that divide and connect us, impossible through and through.

+++

Hannes Verhoustraete

is a filmmaker and artistic researcher. His PhD project Hegemony and historiography: the documentary film essay as palimpsest (KASK School of Arts, Ghent) focuses on the essay as a form of writing history. He is also an editor for the online film magazine Sabzian.be.

Broken View premiered at the Courtisane Festival in Ghent (29 March-2 April 2023). Watch the trailer on film distributor Avila’s website: avilafilm.be/en/distribution/film/broken-view.

Noten

- Vantemsche, Guy. Belgium and the Congo, 1885-1980. Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 81. ↩

- The film was made within the context of my PhD project in the arts at KASK School of Arts and within the B-magic joint research project on the use of the magic lantern in Belgium. I made use of materials from various archives such as KADOC (Liège), FOMU (Antwerp), Museum dr. Guislain (Ghent), ULB (Brussels), AMSAB (Ghent), Instituut voor Tropische Geneeskunde (Antwerp), Mundaneum (Mons), and private collections. About half of the material used in the film was located and scanned by researchers of the B-magic project, to whom I am most grateful. ↩

- Stanard, Matthew G. Selling the Congo: a history of European pro-empire propaganda and the making of Belgian imperialism. University of Nebraska Press, 2011. ↩

- For a history of the magic lantern, see: Mannoni, Laurent. The Great Art of Light and Shadow, Archaeology of the Cinema. University of Exeter Press, 2000. ↩

- See for example: Thompson, T. Jack. Light on Darkness? Missionary Photography of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2012, pp. 207–238. ↩

- Kessler, Frank, and Sabine Lenk. “Projecting Faith: French and Belgian Catholics and the Magic Lantern Before the First World War”. Material Religion, vol. 16, no. 1, 2020, pp. 61–83. ↩

- Mudimbe, V.Y. The Invention of Africa. Indiana University Press, 1988, p. 60. ↩

- Livingstone, David. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. J. Murray, 1899. ↩

-

‘Myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology.’

Adorno, Theodor, and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Verso Books, 2016. ↩ - KAGA, ITG and KADOC together have around 20,000 slides in their collection pertaining to Central-Africa. ↩

- Dillon, Brian. Essayism. Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2018, p. 77. ↩

-

‘Langage et image – sont absolument solidaires, ne cessant pas d’échanger leurs lacunes réciproques: une image vient souvent là où semble faillir le mot, un mot vient souvent là où semble faillir l’imagination.’

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Images malgré tout. Les Editions de Minuit, 2003, p. 39. ↩ -

‘At the end of the eighteenth century scientists and magicians conceived a new type of illuminated show, (…) the fantasmagorie. (It’s) technique depended on several principles. The spectators must never see the projection equipment, which was hidden behind the screen. When the lights in the room were extinguished, a ghost would appear on the screen, very small at first; it would increase in size rapidly and so appear to move towards (…) a terrified audience. (…) A gloomy silence, interrupted only by the metaphysical pronouncements of a stern “fantasmagore” master of ceremonies, or the lugubrious music of a “glass harmonica”, would seem like the prelude to a veritable witches’ sabbath.’

Mannoni, Laurent. The Great Art of Light and Shadow, Archaeology of the Cinema. University of Exeter Press, 2000, p. 136. ↩ - Adas, Michael. Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Cornell University Press, 1989, pp. 153–165. ↩

- Bonhomme, Julien. “Réflexions multiples. Le miroir et ses usages rituels en Afrique centrale.” Images Re-vues, no. 4, 2007. DOI: 10.4000/imagesrevues.147. Accessed 30 January 2021. ↩

- Dukes, Hunter. “Imaging Inscape: The Human Soul (1913).” The Public Domain Review, 17 November 2021, publicdomainreview.org/collection/baraduc-soul. Accessed 15 February 2021. ↩

- Dukes, Hunter. “Imaging Inscape: The Human Soul (1913).” The Public Domain Review, 17 November 2021, publicdomainreview.org/collection/baraduc-soul. Accessed 15 February 2021. ↩

- Graeber, David. “Fetishism as social creativity: or, Fetishes are gods in the process of construction.” Anthropological Theory, vol. 5, no. 407, 2005, p. 411. ↩

- Graeber, pp. 411–413. ↩

- Tonda, Joseph. Le Souverain Moderne, Le corps du pouvoir en Afrique centrale (Congo, Gabon). Editions Karthala, 2005, p. 77. (My own translation.) ↩

- Tonda, Joseph, 2005. ↩

- “James Baldwin Debates William F. Buckley (1965)”. Youtube, uploaded by The Riverbend Channel, 27 October 2012, www.youtube.com/watch, viewed on 4 February 2023. ↩

- I have been poring over Van der Keuken’s writing and films to find a trace of this reference I attribute to him, but perhaps I dreamt it or misattributed shamelessly one sage’s wise aphorism to another. ↩

- Dillon, p. 120. ↩

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. Quand les images prennent position. Les Editions de Minuit, 2009, p. 11. (My translation). ‘Ce mouvement est approche autant qu’écart: approche avec réserve, écart avec désir. Il suppose un contact, mais il le suppose interrompu, si ce n’est brisé, perdu, impossible jusqu’au bout.’ ↩

- See Jean Baudrillard, for instance. ↩

- Schierbeek, B. Weerwerk. De Bezige Bij, 1977. (My translation of the Dutch original: … en even later loop je door het huis // te zoeken naar een boek ‘Die Insel des Zweiten Gesichtes’ // en denk je natuurlijk ligt het ergens onder // altijd ligt het een onder het ander //inderdaad // de ene wereld ligt onder de andere// en van mekaar weten ze ’t ↩

- Daney, S. “The Aquarium (Milestones).” Cahiers du cinéma: Volume Four, 1973–1978: History, Ideology, Cultural Struggle: An Anthology from Cahiers du cinéma, September 1973–September 1978. Routledge, 2000, pp. 248–292. ↩