Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 31 nr. 2, pp. 72-79

Insights behind a unique artistic crosspollination, a conversation with Marie Goudot and Michaël Pomero (Rosas)

With Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music as a starting point, musicians from the Ictus ensemble and dancers from the Rosas dance company came together in the summer of 2023 in an unusual experimental setting around the idea of a toolbox. Kobe Van Cauwenberghe gives insights behind this unique collaboration and discusses with dancers Marie Goudot and Michaël Pomero about their shared experiences.

“Ghost Trance Sessions” met Ictus en Rosas Live in Darmstadt 18/08/2023. Photo by Kristof Lemp.

Two artistic worlds meet around the idea of a toolbox

In 2023, I was invited to take part in an unusual collaboration between musicians of the Brussels based Ictus ensemble and dancers from the Rosas dance company centered around Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music (GTM). I had explored GTM in different settings prior to this collaboration, both as a solo and in a septet version with musicians coming from different musical backgrounds resulting in several performances and two studio albums.1 In preparation of this new collaboration I had given a presentation on Braxton’s GTM for the Rosas dancers Michaël Pomero and Marie Goudot, explaining its modular and holistic philosophy where different compositions can be combined and superimposed like a giant “erector set” or “toolbox”. From their side, Michaël and Marie had been entrusted by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker to create a Rosas Toolbox laboratory, a concept of creative documentation with the intention to make an inventory of the choreographic dictionary used by or developed in the work of De Keersmaeker and Rosas and to make them available to everyone. The idea of the toolbox seemed to be a perfect starting point to bring both worlds together.

Despite the difference in aesthetic qualities, we immediately found striking parallels on a formal level in the works of Braxton and De Keersmaeker. They both think in systems and categories of ways of generating sound or movement. For example, the Rosas Toolbox contains long lists of categories such as “spatial procedures”, “movement generators” or “phrase transformations” which represent different methods to create choreographies and which can be combined and connected in many different ways. Braxton developed long lists of sound classifications which he condensed into twelve sound parameters or “language types” to structure his improvisations and compositions. These twelve types also became larger categories with names like “continuous space logics”, “sequential logics”, “sound mass logics” or “gradient logics” to create an overarching model for his musical systems. The intention in both artists’ work, albeit with very different artistic outcomes, is never to moderate human energies or to create rigid categories to rationalize our relation to art, but, on the contrary, to provoke human creativity through these combinatorial strategies, by inventing provisional categories, mappings and metaphorical and playful names.

Eventually the project involved four dancers from Rosas (besides Michaël Pomero and Marie Goudot, also Mark Lorimer and Sophia Dinkel) who developed the movement material and four musicians from Ictus ensemble (Jean-Luc Plouvier on keyboard, Saynabou Claerhout on trombone, Niels Van Heertum on euphonium and me on guitar) as the core artistic team. The idea was to be joined by two guest musicians from the local community wherever we perform.2 I led the musical rehearsals and brought in the musical material, our focus was on GTM compositions “No. 255” and “No. 264”.

Using the toolbox

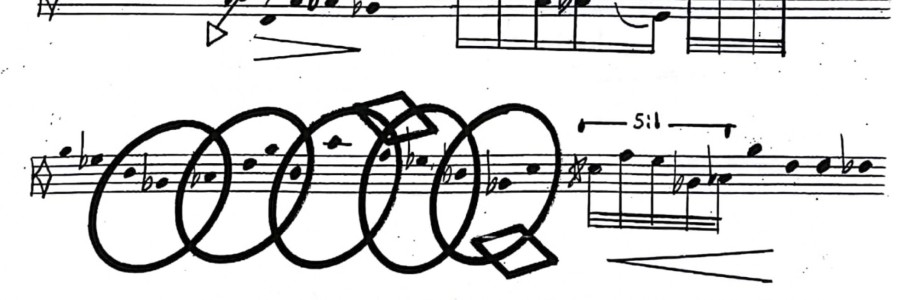

While often associated with free jazz, representing an idea of complete freedom in music, Braxton’s music embraces a more nuanced form of freedom. In his work he continuously seeks compositional techniques and frameworks that challenge performers to navigate between structured systems or predetermined scores and the freedom or agency that comes with the practice of improvisation, always leaving space for unknown outcomes. Within his extensive body of work, the modular toolbox concept is maybe most apparent (or developed) within his system of GTM. GTM is more than a collection of musical compositions, it is a navigational system for the performer to explore Braxton’s entire body of work. Every GTM piece consists of a single line primary melody, seemingly without beginning or end. The musicians start a GTM performance all together on this melody but are then given options to depart from it and to insert improvisations, secondary pieces (short trio-compositions which are part of every GTM score) or tertiary pieces (which can be any composition or part from Braxton’s body of work). Performers can thus select and overlay different sub-compositions, adding improvisations, creating sub-groups of musicians etc. This results in a distinctive musical performance practice where the goal is not so much about perfecting the written scores, but on establishing a shared language and trust to navigate the musical process collectively while preserving individual agency.

For the dancers, maybe the biggest challenge was adapting this ethos into their physical practice in space, of using specific choreographic structures and strategies, whilst maintaining a level of spontaneity and agency in an ongoing process of exploration, mirroring Braxton’s view of his system as a continuous evolution rather than a static destination.3 In order to do this, the Rosas dancers developed several different strategies, using their Toolbox to create a dialogue with Braxton’s GTM system. I’ve written earlier about GTM from a strictly musical point of view, for this article and interview I will mainly focus on the dancer’s perspective and their experience of bringing both worlds together.4

One aspect was to match the “stable logics” of Braxton’s written scores.5 So, for instance, instead of the primary melody of GTM they created a common movement phrase, or “Braxton phrase”, based on Braxton’s drawings of movement positions from his Pine Top Aerial Music compositions.6 They chose eighteen positions which they then mapped onto the space using a “magic square” and a combination of straight lines and curves to make connections between the positions on the “magic square”, a common Rosas procedure.7 The four dancers each also created a solo for the four secondary compositions of the GTM score, anchoring it to one of the members of the ensemble. In addition to this, we used a selection of tertiary compositions from Braxton’s body of work to be used at any given moment in the performance. The dancers built their movement phrases on top of these tertiary compositions sometimes taking inspiration from previous Rosas material.8

"Braxton Phrase" example, using Braxton’s drawings of movement positions (from PTAM) into the choreography. Photo by Kristof Lemp.

Then there are the many moments of improvisation or “mutable logics” that take a central place in the performance of Braxton’s work. He developed his Language Music system, a set of twelve sound parameters, to structure improvisation in his work. The dancers used several tools from the Rosas Toolbox as a way to apply similar “mutable logics” into their choreography. They used so-called “movement generating” tools with names such as “point phrase”, “only circles”, “flocking”, “parallel lines” or “democratizing the body” to match the sound parameters of Braxton’s Language Music system.9 In order to reflect Braxton’s holistic approach where several compositions can be combined or superimposed, the choreography also involved the use of video monitors that were positioned around the dancefloor, and which showed excerpts of previous choreographies from the Rosas repertoire. The dancers could use these as a continuous choreographic video score and insert excerpts of it in real time at any given moment into the performance.

Within a performance of GTM the musicians can always cue each other into playing a secondary or tertiary piece or to improvise. But in this context, this form of inter-musical communication was expanded towards the choreography as well. In navigating the musical and choreographic process, not only could the dancers receive cues from the musicians, they could also cue the musicians. For example, they could start a solo linked to a specific secondary composition or loop a movement phrase linked to a specific tertiary piece which then served as a cue for the musician(s) to play that particular piece. The open structure and use of improvisation also allowed for many ad hoc combinations between movement and music to arise. Where the dancers used their own tools to match Braxton’s twelve “language types” for musical improvisation, their spontaneous choreography at times also served as a real-time extension of the musical score for the musicians to spontaneously interact with. The goal here was to establish a collective process or “event space” of ten interacting performers.10

Floor Pattern with "magic square" and movement trajectories for the dancers using straight and curved lines. Photo by Michaël Pomero.

In order to facilitate an open and spontaneous communication between musicians and dancers during the performance, the musicians were positioned on the four corners of the dancefloor, so everyone could see each other well. Given the amount of freedom, we decided on an overall structure and a general length of forty minutes for a performance. We would ‘meet’ all together in the middle of the performance on Braxton’s “Composition No. 55” which I cued in as a tertiary composition into the performance, and then again at two thirds into the performance (what the dancers refer to as the “golden section”) this time with “Composition No. 69Q” cued by the dancers. Besides the beginning (everyone starts together in the primary melody of the GTM score) and these two fixed moments, the general flow and order of compositions and improvisation of the GTM performance was left completely open.

After a three-week rehearsal period at the Rosas studios in Brussels in June 2023, the first two performances took place as part of the Darmstadt Summer Course for New Music on August 18, 2023, where Ictus was joined by guest musicians Katherine Young (bassoon) and Andreas Borregaard (accordeon). Two more performances took place on September 20 at Macba in Barcelona, here with guest musicians Sarah Claman (violin) and Lucas Messler (percussion). After these first experiences I sat down with dancers Michaël Pomero and Marie Goudot to talk about this unique collaboration. We discussed the philosophy behind the Rosas Toolbox and its connection to Braxton’s music, but also the role of improvisation in both music and dance, the social interaction (“it’s a social dance”, as Marie declared) and the importance of trust, openness and constant exploration in the creative process. This revealed interesting tensions and parallels that, in my view, shed new light on collective artistic and creative processes across both fields, especially when it concerns the topic of agency. I was already convinced that Braxton’s open-ended approach regarding individual agency, which uniquely combines in-the-moment decision-making with predetermined structure, offers a fresh perspective on musical performance practice. It was fascinating to see how this philosophy also translated into the field of dance and, through the toolbox-concept, allowed both practices to inform each other, resulting in an ongoing artistic process where musicians and dancers interacted as a unified group of ten performers within Braxton’s “event space” of the GTM system.

A conversation with Marie Goudot and Michaël Pomero

Kobe Van Cauwenberghe: In March 2021 I gave a workshop on GTM with Ictus and students from their advanced master program, and I remember you were there as well. Where was the connection made to start this collaboration with Rosas Toolbox?

Michaël Pomero: For a couple of years Marie and I kind of worked as an intermediary between Rosas and Ictus. They were thinking about making new creations together, so we would go back and forth between Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (Rosas) and Tom Pauwels and Jean-Luc Plouvier (Ictus) to listen to some of the music they had in mind and look for interesting potential future collaborations. At some point we had three different musical works that we presented to De Keersmaeker, one of which was Braxton’s GTM, and this was the one that she was the most intrigued by.

Kobe: But then it evolved into the Rosas Toolbox, that came after?

Marie Goudot: Yes, during that time we also started working on the Toolbox project and it occurred to us it was potentially very related to Braxton’s music. After we had our first meeting where you gave this lecture about Braxton’s work and more specifically GTM, and we learned a bit more about how the music worked, how it’s organized, it became obvious that accessing it through the Rosas Toolbox would be a great starting point.

Kobe: Can you explain the concept of the Rosas Toolbox?

Michaël: Officially it’s a pedagogical project, to make a collection or inventory of all the compositional tools and choreographic procedures that have been used in the building of Rosas (repertoire) throughout the last forty years.

Marie: So not necessarily tools that De Keersmaeker or the dancers of the company created, but even things that the dancers would bring with them such as specific methodologies coming from people that they’ve been working with in the past. In a way it’s a resource of choreographic methods.

Michaël: And we worked for a few weeks together with Mark [Lorimer] and Cynthia [Loemij]. We gathered over a hundred different tools or different choreographic procedures and organized them in different categories, such as “temporal procedures”, “spatial procedures”, “generating material”, “transforming material” and things like that.

Kobe: I didn’t even know that you made so many categories. It immediately resonates with Braxton’s approach to categorizing, with his “sound classifications” for example. The parallels with the Rosas Toolbox are striking.

Michaël: Yeah, the connection between the two worlds was obvious on a formal level. But the philosophy behind it is very different.

Marie: Which is also extremely interesting, to see how two giants in their own field have so many parallel lines and the end result is so different. De Keersmaeker is in many ways the opposite of Braxton. For De Keersmaeker these formal elements exist for her to structure everything and to have control on everything.

Kobe: And in Braxton’s philosophy the structure exists to allow the performer to use it to their own needs.

Michaël: Yes.

Marie: Personally, I was interested to use the Rosas Toolbox and try to open it up towards Braxton’s approach. But it’s not so easy when you’re used to working within a very controlled structure where you know exactly what you have to do. So, you have to rethink the material itself or the resources itself.

Michaël: This brings us to our own perspective on the Rosas Toolbox. For us it is also a way to bring tools to people so that they can either transform those tools or use it as a source of inspiration to build their own tools and not necessarily exactly in the same way as they were used in Rosas. So, for us Braxton’s way of working resonates exactly with what we had in mind with the Rosas Toolbox: you get inspired by methodological tools that you can bring somewhere else.

Marie: Rosas’ intention for the Toolbox was to preserve/archive the legacy of De Keersmaeker, which is not the same thing.

Michaël: The original idea of the Rosas Toolbox came from Marie and me several years ago and for us it was a way to treat the legacy or the artistic heritage of De Keersmaeker in another way than repertoire, something more like a dynamic open source archive.

Kobe: That does sound more like Braxton’s intentions with his work. One of the keywords for Braxton is ‘agency’. I think this is a very important aspect in his music and his writing, namely that he offers something to the reader or creative musician which they have to respond to in their own voice.

Michaël: I think that’s how we bridged both worlds in our collaboration. We imported some of the tools from the Rosas Toolbox, but we made them much more open and with a lot more agency from the performers to use them in the moment itself.

Marie: Working with Rosas, as a performer the agency is reduced to the interpretation of something that is extremely scored and precise. So, there is agency but it’s not in the same kind of spectrum as for the musicians performing Braxton.

That’s a really important aspect of the performance: we perform as a group of ten, and not six musicians with four dancers responding to the music.

Kobe: In a sense this is the same confrontation I had to go through as a classically trained musician. I was used to performing extremely precise notated pieces in which the level of agency is very much limited to very small details of interpretation. And then here suddenly you come into a world where you have a lot of freedom, but still set within a framework of instructions and written scores. This was a similar experience for you?

Marie: Yes, we were facing similar challenges because doing this project, we as dancers were at least as much in an improvisational mode as the musicians. But that was also our goal, to have ten performers (six musicians and four dancers) entering the same world, but with different tools because we move in space, and you create the sound in space.

Kobe: How did you translate these complexities of Braxton’s GTM and his holistic approach into the choreography or into your own way of working?

Michaël: Very fast into the process we realized that we needed something that would be related to your use of the musical score. We needed something that could be an analogy in movement to be able to be in the same game as you. Because at first, we mostly improvised and tried to find improvisational tasks that would relate, but very fast we realized that we also needed a basic movement structure that would be written. So, we built a movement phrase, or what we called “Braxton phrase” that became our main “score”, like you have the primary melody in GTM.

Kobe: What you call the “Braxton phrase” is based on the drawings from Braxton’s Pine Top Aerial Music. So, you created your own movement, or a fixed phrase based on those drawings?

Michaël: Yes, we selected eighteen of them to have different levels or positions and then we placed them on what we call the “magic square”, to give them a certain direction. So of course, the shapes are then kind of twisted.

Marie: They are not flat, like in the 2D drawings, so in volume and in directions they become more complex.

Michaël: And then we wrote a simple movement sequence, where someone goes to the first drawing of Braxton followed by another person who goes from that picture to the next, moving from one drawing to the next drawing, with a movement in space that is given direction through the “magic square”. So that’s how we were able to collectively build the movement phrase.

Marie: We didn’t actually have so much time to develop it, it was a three-week process. There would have been many ways to use these drawings in order to build up the material. We decided to be efficient to have some material quickly, to see how we could play with it. Retrospectively, we could have used a bit more time to build up a more consistent phrase. In my experience when performing it, it felt like we didn’t always have enough written material, the phrase was a bit short.

Michaël: In comparison, a Rosas process is usually at least sixteen weeks of rehearsal, so yes, we had to be very fast and efficient in our decision making. But some of those tools are already kind of imprinted in our bodies. Like the “magic square”, also for the other dancers (Mark Lorimer and Sophia Dinkel) they instantly knew what it meant and how you move in the space using that tool. It was a way to create something fast that would leave a trace in the space. So, a lot of what we wrote follows exactly the same trajectory on the floor which allowed us to have a consistent use of the space.

Kobe: It’s interesting, this lack of time that you experience. From a musician’s perspective three weeks already seems a lot. In Braxton’s way of working, it’s probably too much. Braxton famously gave instructions not to rehearse too much so that you’re slightly nervous, to allow for uncertainties or unknowable things to happen in order to be more intuitive in the process and to really explore the music in real time.11 Is that something you’ve also felt as beneficial to the work, not having enough time, so that you are kind of forced to find ways to respond in the moment?

Michaël: Yes, I think if we would have had a twelve-week process, we would have gone further away from the ideas of Braxton.

Marie: Yes, absolutely, the fact of having three weeks forced us to stay close to his principles and, actually, not to fall into De Keersmaeker’s principles, which we know so well.

Michaël: That would have been another project. If she would have directed it, she might have built something that is extremely strict on this music that is extremely open. This could also have created a friction that would have been quite interesting.

Marie: Most likely that’s what she would have done. But yes, it would be another project and it would most likely be good as well. Because of the time pressure we stayed on the Braxton side, that’s for sure. But then again, also through the context of the Rosas Toolbox, which in our mind stayed closer to Braxton’s way of working than the traditional Rosas production.

Michaël: This way of working also made us feel more like one of the Ictus musicians performing it then Rosas dancers. In a Rosas performance we would never do what we are doing here, because the choreography in a Rosas production would be pre-set. In our collaboration there is very little that is set in advance.

Kobe: In addition to the openness of the scores and the materials from Braxton, for each performance there were four Ictus musicians as core members of the ensemble and then two different guest musicians. So, also the instrumentation and overall sound of the group was very different every time. How did you experience this kind of radical openness? What was your response to this in your choreography?

Marie: As dancers it was something we never did before. It’s not really a problem for us to have different instrumentation. It goes with the project itself, right? Having drums during the rehearsals, but not for the performance in Darmstadt was extremely challenging, however.

Michaël: That was maybe the most challenging, yes, to lose the percussion. Because in our bodily practice it is the instrument you can very easily relate to. The fact that there are wind or string instruments doesn’t make such a big difference. But we also kind of anticipated that via our Toolbox by assigning ourselves to different corners/musicians, so I was always with you, Marie was paired with Nabou [Claerhout], Mark with Jean-Luc [Plouvier] and Sophia with Niels [Van Heertum]. So, we also created this one-to-one relationship that we use sometimes in symbiosis or in contradiction.

Marie: And it’s a safe space. Whenever it’s too chaotic or we don’t understand, we can always ‘switch on’ our dancer related instruments. We can anchor what we do on our specific corner/assigned musician.

Kobe: It’s interesting you describe it as a safe space. It comes back to some of the instructions that Braxton gives when he says, “If you play too perfectly, you played it wrong”. So, you can’t really make mistakes, you just have to work around it creatively and collectively. I have also found that this creates a safe space within the performance practice of the music, which is quite rare, especially coming from classical music where you feel very quickly judged whenever you make a little mistake. Do you feel the same in your approach to it from the perspective of dancers?

Marie: We implemented this approach more and more. In Darmstadt it was still a bit stricter in what we were doing. After listening to the lecture of Braxton himself, he insisted on the idea of the surprise. “You have to look for the surprise”, things like that. When we performed it again in Barcelona we already went more in that direction. We took more opportunities to slide over or even away from what we had planned as a structure.

Kobe: Within this safe space there’s also a strong sense of a shared responsibility, so it’s not like you can do whatever. There is no way to make mistakes, but this openness also requires a form of discipline, to be able to accept the unknown. And to me this means taking away or suspending all forms of judgment while performing the music. Or maybe not all forms of judgment, you still have to make choices and judge in the moment which direction you want to take the music, but I’m talking about judgment in the sense of whether this is good or bad. And when listening back to recordings afterwards I’ve always been incredibly surprised by what’s happened in the music. Is this something you also experience from a dancer’s point of view, suspending judgment, allowing the piece to evolve?

Michaël: One of our primary rules within our instructions was to do what you think the space needs, which also relates to Braxton’s principles. And do what the space needs could be anything, you don’t actually judge the quality of what you’re producing. You judge the fact that the space needs that intervention in that corner there, or it needs someone to cross the space like that. But also because of the quality of the entire group and the intimacy or the trust that we have between the dancers (Sophia, Mark, Marie and I), it opened that space for taking that non-judgmental freedom and responsibilities at the same time.

Marie: That’s also why the idea of working with guest dancers, like you worked with guest musicians, is not so easy for us. Because a safe space is also a “trust space”. With our current group of dancers there is no judgment because we really trust each other, we’ve worked together for years and know each other very well. We’re a multigenerational group, each one of us is carrying a different understanding and brings their own ideas.

Michaël: But then going through this process together and the fact of having performed it four times by now, we also created a common understanding of what we are doing. And I think it comes back to the big difference that musicians have a score, and we didn’t have a score to start with. To me the movement phrase that we created is one score, but the understanding of the group, and the relationship with each other is clearly a “score” as well.

Kobe: So, your understanding of each other and the way that you know each other, in the movements and choices that you make, you also use it as a “score”?

Marie: Exactly.

Kobe: That is very interesting.

Marie: Yes, because if you would put each one of us in a different group or another creation, we will not come up with the same materials that we’re using in the Braxton project. So somehow, we did materialize a space and time that is very specific to this project. We have to be able to surrender ourselves to each other. During our three weeks of rehearsal, we worked hard on methodology, trying to find the link or bridge with the music, but towards the end, it was when we were already in Darmstadt actually, Sophia made the remark that we don’t touch each other enough, that there is no “compressed space”. And in one rehearsal, we changed everything, and there I feel we really aligned with Braxton, you know, we understood what it should be about, it’s a social dance. And so that’s also why it’s hard for us to imagine or recreate that kind of intimacy, bodywise, with guest dancers that we don’t know so well. There is the concept and theory on the one hand, but concretely, what we do as dancers is that we touch each other a lot and it gets extremely intimate, not in the emotional sense, but physically.

Michaël: And you can hurt yourself when you’re dancing with someone that you don’t know yet. We could still think of a methodology that would take this into account, but it would demand much more time in comparison to how musicians work and how they can collaborate in a much more ad hoc way.12

Kobe: Yes, I see. And among musicians, especially when you don’t know each other well, it can of course also clash, but you won’t hurt each other physically. These clashes are actually part of the music, the real challenge working with musicians you don’t know yet is when they’re not on the same page in terms of the philosophy of the music. They might be able to play the scores perfectly but in this case that’s not the point. It’s about this openness and freshness, to bring your own voice into it.

Michaël: Yes, and similar to the musician’s role, we as dancers are as much performers as we are choreographers creating the movement in real time. So, you kind of need that trust there too. I know that I can lose myself in my own task because I know that Marie, Mark or Sophia is going to take the right decision to create a counterpoint to what I’m doing, to balance it. And in a way you need a choreographer’s eye to be able to do that. It’s not only about the quality of the dancing. It’s understanding what the space needs. So, we need to be able to build that trust as well so that you can surrender to your own task and know that the others are going to make the right decision in the moment. Creating that kind of mutual understanding and trust demands a lot of time.

Kobe: After the rehearsals and first performances in Darmstadt and Barcelona, how do you feel the piece evolved?

Michaël: I think we’ve gotten closer to Braxton’s world, or his principles. We’re a little more daring from the inside as we feel more and more secure with the material, because we have a better understanding of what the performance needs. Similar to you as musicians, we have a lot of things that we know can happen. Each one of us has a list of material we could bring in, and more and more we let ourselves go in directions that we never even talked about between the four of us. Closer to what you do as musicians we are more and more going into a real improvisational mode that brings us to invent things in the moment.

Marie: Yeah, and also in the relationship with the musicians, there is much more interaction happening. Especially with the four Ictus musicians, maybe a bit less with the guest musicians, which is totally understandable of course.

Michaël: Yes, but even there, when we performed in Barcelona at some point my shoes were squeaking on the floor and the violin player Sarah Claman played exactly the same frequency on her instrument and we had a nice duo for a few minutes. This was only the first time we played together.

Kobe: That was so nice.

Marie: Yes, indeed! But it’s true that from the six musicians, knowing that four of them are the same creates a nice common ground for each performance.

Kobe: At some times the movement really flows along with or in response to the music and at other times the music responds to the choreography. I was very happy to see how this all came together quite organically. Let’s talk a bit more about this relationship between musicians and dancers in the performance. Within GTM the musicians can cue each other to play specific compositions, written material or improvise, but in our performance the dancers can also cue the musicians and vice versa. How did that work for you?

Michaël: We realized already at the very beginning of the process that we needed some kind of interdependence and that it could not go only one way from the music to the dancing, but that we could also communicate the other way around. And the more we perform it, the more this is happening because we understand each other better and better. But from the beginning it was a crucial point that the dancing wouldn’t constantly be dependent on the music, and we could also reverse the roles so that the dance can cue the music or implement things in the music. And even in the first performances in Darmstadt when I looked back at the recording you can already see passages where for example Nabou is improvising on what Marie is dancing, where she is translating in sound what Marie is producing in movements. And that’s a really important aspect of the performance, we perform as a group of ten, and not six musicians with four dancers responding to the music.

Marie: Even though that does happen at some points, it’s just about finding the right balance.

Michaël: This was also a point of feedback from some of the musicians, saying that the more we perform, the more they are actually looking at us instead of looking at their scores. So, the visual information became part of their musical score as well. That’s also super interesting to play with.

Kobe: Speaking of improvisation from a more general point of view, what is the perspective on the role of improvisation within dance? In music the practice of improvisation is still very much linked to a strict categorization in terms of musical genre, which seems to be one of the reasons why Braxton as a composer is much less recognized, because his music uses a lot of improvisation, even though he has composed an incredible amount of work. What’s your vision on this diversity of practices?

Michaël: I think we have much less subdivision of genre. What we call contemporary dance is so wide. It can take so many different forms or concepts of performance. We just gave a two-week workshop for the master program at P.A.R.T.S. which was partly inspired by the experience of working on the Braxton project.13 The newest generations of makers use very little written material or no notation at all. Most of the movement material is generated and even performed through improvisation. And so, we worked for two weeks on the pros and cons of the use of written material and improvisation. And we ended up asking them to create a choreographic structure or system where the two could coexist. There is a friction there, with people from the generation of De Keersmaeker most of the time everything would be written. With those twelve students in P.A.R.T.S., none of them writes in that same manner.

Marie: You give the example of De Keersmaeker, but at the same time there are people like Deborah Hay, so there are really different worlds in dance as well.

Michaël: But the fact that you use improvisation in it, doesn’t give it a different label, is what I mean. It’s still contemporary dance. If you take a piece from Deborah Hay, which is completely based on improvisation, we wouldn’t call it “free dance” as in “free jazz”. Just like a piece by De Keersmaeker which uses no improvisation at all, they are both “contemporary dance”.

Kobe: That’s very interesting. In music there are even distinctions within the fields of free improvised music. The term free jazz is historically linked to the United States and the jazz tradition, but then you also have free music or free improvisation, which is inspired by free jazz, but linked to the European scene. And when you look at it from a western classical music perspective, there is still a very strict distinction between composing and improvising, so there are many distinctions and categories in music. The experience of performing Braxton’s music with musicians coming from different musical backgrounds, both in improvised or strictly score-based music, made it clear to me that allowing for this diversity of practices is a very beneficial way to renew our practice as performers in music and to go beyond these often-artificial boundaries.

Michaël: In comparison, even in the most strictly written piece of choreography, you still generate this writing most of the time through improvisation. So, improvisation is in a way always there, at the source. If we have to build a movement phrase, even with Rosas, we will start by improvising the task until we find something and then you write or carve into a written phrase.

Marie: There is not such a thing as an “academic ballet”. The only pre-set steps that exist in dance are the ballet steps. Or a few modern techniques, but it is not something that we use anymore. So, everything has to be renewed and reinvented all the time. In dance we don’t have scores, we always start from scratch.

Kobe: A last question about the Rosas Toolbox, it is intended as a tool to create new choreographies or to use as a source of inspiration, to use elements of it. But now with this Braxton collaboration you’ve created something with it, is it still the Rosas Toolbox then, or is it now a piece of its own?

Michaël: It now is a piece of its own, yes.

Marie: And which will definitely evolve independently from the Rosas Toolbox.

Michaël: Because of the nature of Braxton’s music, you never know what to expect at any moment, which we also tried to apply to what we are doing. And the Rosas Toolbox is there for extracting tools to be able to respond, but the way it was used in Rosas is to frame things so that they are exactly reproducible. And we’ve been using it in this project to sometimes distort and open up original tools. So, in that sense the Braxton project became something different than the original Rosas Toolbox.

Marie: The way it’s been evolving, we could already sense that there are things that we fall back on, to feel safe. We start to create little bubbles of material of which we know it works. Eventually, when we perform it more and more, we have to keep a sense of surprise, and as dancers, if we stay too close to the Rosas Toolbox, we won’t be able to do that. We will instinctively fall back on what we know, to stay safe. And that is opposite to Braxton’s ideas of performance. We are all aware that there’s this tendency that we have to fight against. Which is something I found extremely exciting, actually. That’s also why it is great to work with Mark and Sophia and Mika because we know from each other that we will fight against this tendency, where others might hold on much more to the material that works and keep it. With the four of us we are aware and know how we want to work to keep it open and leave space for instant decision making. But it’s really a part of our nature as dancers, also as a security measure, to only do what you know.

Kobe: There are many parallels with musical practice here. Even completely free improvisers often have their patterns or vocabulary, or their muscle memory. This is also why Braxton created all these “sound classifications” as a way to inspire or challenge his playing and change it, make it different and look for the unknown.

Marie: Yes, and that’s why also for us it would be great to go on with this project. Because in a usual Rosas production, there’s a research phase of twelve weeks or so where the piece is made and once the piece is made and rehearsed, it’s completely set and ready to go on tour. With the Braxton project we had three weeks to do a lot of brainstorming and we rehearsed and performed, but the piece is still evolving, the research is still going on. And for us that’s an extremely rich experience, the fact that you know that the next performance will bring the piece somewhere else and it’s an on-going research project.

Kobe: That’s also what I found very appealing and challenging in performing this music, the constant process.

Marie: It can really change our approach to working.

Michaël: One of the things that resonate very strongly coming from Braxton’s lecture in Darmstadt is where he called himself a professional student of music. And for me, as a performer in this project I feel like we are all professional students making the performance. It could sound like false modesty when he says that, but it’s not, because he’s putting everything structurally in a way that you are to continue studying.

Kobe: And he actually also used the term toolbox in his lecture. In the hand-outs he gave us he describes his body of work as “a toolbox that can be reconfigured to demonstrate intention, construction and exploration on the tri-plane”. I think we came pretty close to that!

+++

Kobe Van Cauwenberghe

is a guitarist and researcher currently pursuing a PhD in the Arts at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp. His current research is dedicated to the music of American composer Anthony Braxton which over the past years led to several publications, concerts at internationally renowned festivals and venues and two critically acclaimed album releases.

Noten

-

The studio albums are: Van Cauwenberghe, Kobe. Ghost Trance Solos, all that dust, 2020. allthatdust.com/releases/ghost-trance-solos/; and: Van Cauwenberghe, Kobe, et al. Ghost Trance Septet Plays Anthony Braxton, el Negocito Records, 2022. elnegocito.bandcamp.com/album/ghost-trance-septet-plays-anthony-braxton.

I had already given a workshop on Braxton’s GTM for musicians of the Ictus ensemble and students from their advanced master’s program in March 2021. A documentation video can be seen here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9egTwgYuRk&t=29s.

In terms of my own musical background, I’m a conservatory-trained classical musician, specialized in contemporary music, mostly score-based with some experience in free improvisation. ↩ - For the rehearsals in Brussels, we were joined by students from the Ictus advanced master program: Anita Cappuccinelli, Lucas Messler (percussion), Maris Pajuste (voice), Luca Piovesan (accordion), Marina Delicado (keyboard) and Leonardo Melchionda (guitar). ↩

- For Braxton, his holistic “Tri-Centric model” is “a system of becoming, not a system of arriving.” See: Braxton, Anthony. Tri-Centric System Notes. New Haven: self-published, 2016, p 27. ↩

- Van Cauwenberghe, Kobe. “A Ritual of Openness. The (Meta-)Reality of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music.” FORUM+, vol. 28, no. 1, 2021, pp. 48–57. doi.org/10.5117/FORUM2021.1.VANC. ↩

- In his description of the “Tri-Centric model” Braxton often refers to the three pillars of (1) “stable logics”, or the written scores and compositions, (2) “mutable logics” or improvisation and (3) “synthesis logics”, the unknown element that is part of every performance. See: Braxton, 2016, p. 313. ↩

- For more information on Pine Top Aerial Music and Braxton’s own use of movement and choreography. See: Bernsen, Rachel. “Pine Top Aerial Music.” Sound American, vol. SA16, 2016. archive.soundamerican.org/sa_archive/sa16/sa16-pine-top-aerial-music.html. ↩

- Within the Rosas Toolbox the “magic square” is an example of a “spatial procedure”. “Magic square” is a mathematical diagram of the numbers 1–9 organized in a square so that any straight line, row, column or diagonal has the sum of 15. It originated in China seven centuries before Christ and is equally found in many ancient cultures. It creates a multi-direction pathway by following the numbers in order (1, 2, 3...) through the space or kinesphere and thus challenges frontality. ↩

- The tertiary compositions we used were No. 6f, 23h, 40f, 55, 69Q, 108a–d, 193 and 304. ↩

- “Democratizing the body” is directly inspired by Arnold Schönberg’s dodecaphonic twelve-tone system where all twelve notes of the chromatic scale had the same importance, instead of being identifiable as belonging to a tonality. “Democratizing the body” is a tool where one assigns twelve points to twelve body parts (foot/toes, ankle, knee, hip, belly, finger, wrist, elbow, shoulder, chest, neck, head) and by using each part as a movement generator in a sequence, a new phrase can be written. There’s a clear resonance here with Braxton who often cites Schönberg as a major influence and whose Language Music system of twelve sound parameters can certainly be seen as a post-serial framework for improvisation, not unlike the Rosas tool of “democratizing the body”. ↩

- “(Braxton’s) musical systems supply architectural foundations for ‘event-spaces’, where all performers (…) can take part and engage with one another.” See: Dicker, Erica. “Ghost Trance Music.” Sound American, vol. SA16, 2016. archive.soundamerican.org/sa_archive/sa16/index.html. ↩

- Braxton, Anthony. “Introduction to Catalog of Works.” Tri-Centric Foundation (blog), 1988. tricentricfoundation.org/introduction-to-catalog-of-works-1988. ↩

- A few months after the interview Michaël told me via email that they are exploring the possibility of adding two guest dancers, so a future performance would have six musicians and six dancers. ↩

- P.A.R.T.S. (Performing Arts Research and Training Studios) is a school for contemporary dance created by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and based in Brussels. ↩