Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 31 nr. 2, pp. 20-25

I'm sorry I made you feel that way. Empathie en welzijn verkennen via virtuele lichamen en generatieve AI

Frederik De Bleser, Martina Menegon, Lieven Menschaert

The interactive installation “I’m sorry I made you feel that way” explores the intimate connection between a virtual body and physical well-being by linking real biometric data to a digital body representation. Developed during Martina Menegon’s research visit using open-source tools, the interactive installation was exhibited in Vienna, London, Lisbon, and Pristina. It highlights generative AI’s potential to create empathic digital connections, raising questions about the value and care of virtual bodies when linked to the well-being of a physical person.

De interactieve installatie “I’m sorry I made you feel that way”exploreert het intieme verband tussen een virtueel lichaam en lichamelijk welzijn door biometrische gegevens te koppelen aan een digitale representatie van het lichaam. De interactieve installatie werd ontwikkeld tijdens het onderzoeksbezoek van Martina Menegon met behulp van open-source tools en werd tentoongesteld in Wenen, Londen, Lissabon en Pristina. Het belicht het potentieel van generatieve AI om empathische digitale verbindingen aan te gaan en roept vragen op over de waarde en zorg van virtuele lichamen wanneer deze gekoppeld worden aan het welzijn van een fysiek persoon.

Although originally a word of Sanskrit origin, the term “avatar” (meaning “alter ego”) was first used to refer to a digital representation of oneself in the 1980s, in the computer game Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar developed by Richard Garriott. Garriott wanted the player to feel responsible for every in-game action and he believed the only way to achieve this was to have the players playing themselves. Early players from the online game Habitat were already so connected with their virtual avatars that they staged a virtual protest when administrators tried to change the rules of the game.1

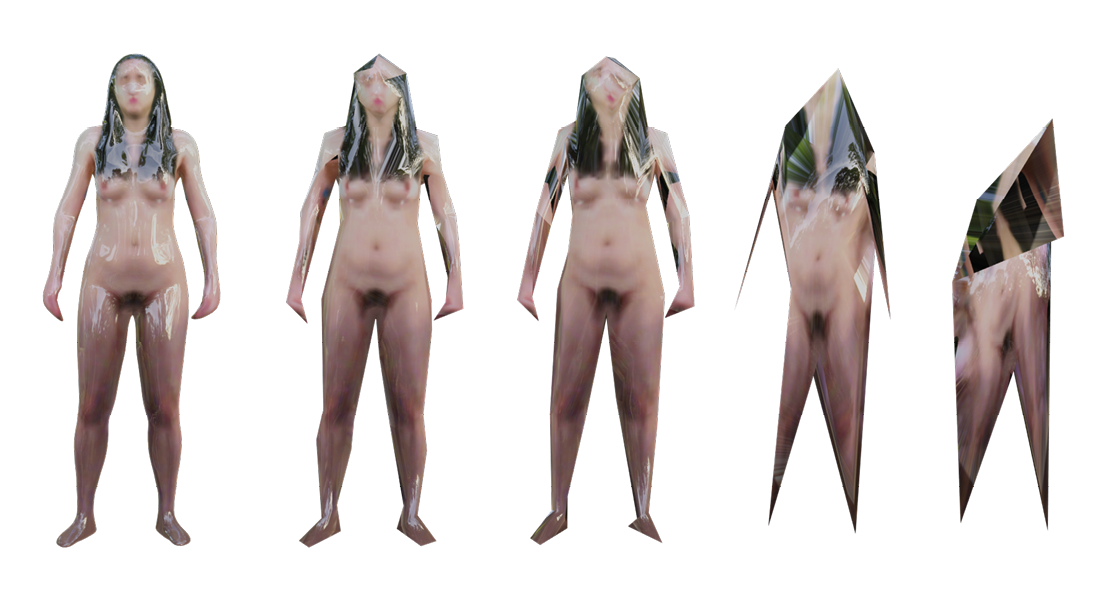

A progression from a detailed to low poly representation.

The virtual world of Second Life exemplifies the depth of connection users can form with their digital avatars.2 Unlike traditional video games, Second Life allowed users to engage in a broad spectrum of activities, from socializing to creating and trading virtual goods, through their avatars. These environments blur the distinction between physical and digital selves. In these spaces, avatars become more than virtual representations; they are extensions of the user’s identity, embodying complex emotional investments.3 Even when people might see the avatar as a sort of virtual pet, like a Tamagotchi, they still deeply care for it and sympathize with it.4

Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto delves deeper into this complex relationship by framing avatars and digital companions as part of our cyborg identities.5 Haraway argues for a cyborg identity that transcends traditional dualisms of mind and body, human and machine, promoting an understanding of deep emotional and empathetic connections with digital entities. This view blurs the boundaries between the human and the digital, and argues for a more integrated, symbiotic coexistence. However, we must be cautious about this sense of embodiment. Laura Aymerich-Franch, a leading expert in behavioural science, underscores the ethical and psychological implications of avatar embodiment. Her research emphasizes the need for responsible innovation to ensure user safety, privacy, autonomy, and dignity. This careful consideration is crucial as we explore how digital entities can influence emotional well-being, impact social interactions, and shape identity in virtual environments.

Having engaged in discussions about the intersection of digital and physical identities for several years, we found a way to explore these ideas together with the goal to create a novel AI avatar that could be altered using biometric data. The wearer’s physical well-being reflects in the visual appearance of the virtual avatar, thereby establishing a relationship between the care for the physical body and the mark it would leave on the virtual body. This embodies Haraway’s vision by creating an avatar that is not just an extension but an integral part of the artist, reflecting her physical well-being in real time.

Method

This project was a collaborative effort involving Frederik De Bleser and Lieven Menschaert, researchers of The Algorithmic Gaze at Sint Lucas Antwerpen, and Martina Menegon, educator and digital artist. The Algorithmic Gaze focuses on democratizing AI for artistic use through the development of open-source tools and methodologies.

Martina Menegon’s work integrates her 3D-scanned body as a digital avatar, allowing her to explore fluid identities through interactive installations and extended reality. This project unfolded over multiple days in July 2023 in Antwerp, allowing Martina to engage deeply with the tools and methodologies developed by the research group.

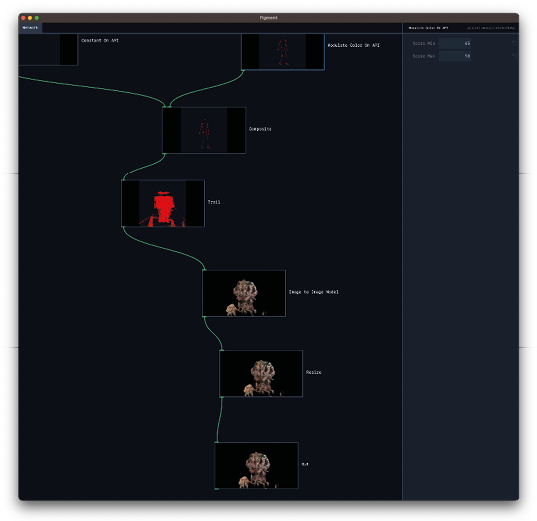

Screenshot of the Figment application showing the custom network developed for this project.

The concept was to connect biometric data from Martina’s Oura smart ring, which she wore continuously during and after the project. A smart ring, much like a smartwatch, can track sleep, activity, and wellness. We examined pertinent biometric indicators, focusing on two aggregate metrics: the “daily readiness” score, which combines various biometric markers reflecting overall health, and the “daily sleep” score, offering an estimate of the artist’s sleep quality. We felt these two would provide a comprehensive portrait of Martina’s well- being. We used Oura’s API to retrieve the data.6

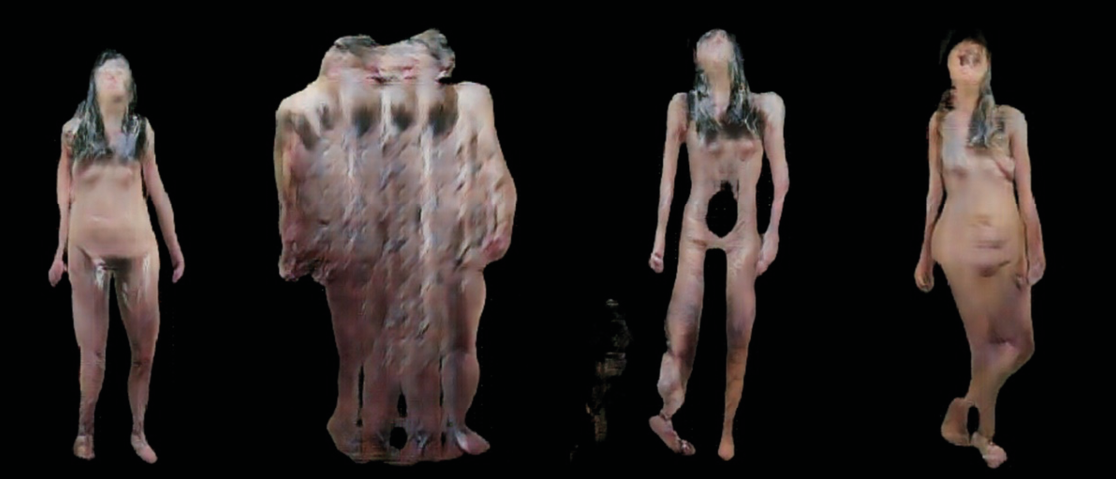

A crucial aspect of our method involves using self-generated datasets. To achieve this, we conducted recordings of Martina in a professional photo studio, incorporating both 3D scans of her body and video footage capturing her movements against a green screen. We then utilized a custom-developed open-source software created during the research project, called Figment, which is specifically designed for preparing large image and video datasets for machine learning. We used the body pose estimation feature in Figment to generate a ‘skeleton’ of her body, which serves as a ‘control image’ for the AI and could be used to drive the interactive installation. To link the health statistics to the skeleton, we created different versions of the physical/digital body, which would be selected based on the health statistics. For example, if she had a high daily readiness score, the digital body would be a ‘clean’ version of the body, whereas a low score would be represented by a low poly, decimated version of the body.

Martina felt a compelling need to maintain her health for the sake of her avatar’s appearance, thereby reinforcing the project’s themes of digital-physical hybridity and empathy.

We developed custom nodes in Figment that would connect to the Oura API and retrieve the latest health statistics. These nodes are specialized modules created to connect to Martina’s smart ring and download its data. These are converted into visual markers, e.g., a white skeleton meant a high daily readiness score, whereas a red skeleton meant a low daily readiness score. In this way, we could interpolate between different versions in AI using a real-time score, showing an ever-changing representation of the artist’s health.

We employed a “trail” node to depict the “daily sleep”, leaving a trace of the movements. The intensity of the trail would vary, being more pronounced with a low daily sleep score and less prominent with a high daily sleep score. Thus, the trail depicted the artist’s fatigued movements as she navigated through the day, consequently rendering her virtual representation less responsive.

The installation is developed using a layered approach, each layer representing a distinct level of interactivity and engagement with the piece. The “technical layer” is the foundation, which integrates biometric data from the smart ring. This data is continuously fed into the system, ensuring real-time updates on Martina’s physical well-being. The next level is the “animation layer”, where the avatar visibly reflects the biometric data. In this layer, the avatar displays a prerecorded idle pose animation when no user interaction is detected. This idle mode gives the avatar a persistent, lifelike presence even in the absence of direct engagement. At the top is the “interactivity layer”, which activates when a person is detected in front of the webcam. In this layer, the system transitions to live pose estimation, allowing visitors to control the avatar in real-time. This interactive engagement enables users to influence the avatar’s movements, creating a dynamic and immersive experience. This multi-layered approach ensures that the avatar remains engaging and responsive, seamlessly blending animation with user interaction.

Results

“I’m sorry I made you feel that way” was exhibited in a solo show at Discotec art space in Vienna, at Artsect DAO Gallery in London, at the group exhibition "Beyond Human" in Artemis Gallery in Lisbon, at the solo exhibition "You know me so well" in Galeria 17 in Pristina (in collaboration with Ars Electronica), as well as online for the group exhibition "Becoming Machine", a pavilion of the WRONG Biennale. The name of the work is an ironic reflection on the dynamics of self-care, where Martina pre-emptively apologizes to her avatar, acknowledging her challenges in maintaining her own well-being.

The installation exhibited in the Discotec Art Space, Vienna, Austria, 2023. Photo by Tina Kult.

The exhibition received positive reactions from the audience. Initially, visitors engaged with the installation in a discovery phase, playfully exploring how their movements influenced the avatar. This initial exploration often led to a deeper connection, as visitors began to understand the direct relationship between the avatar’s appearance and Martina’s physical state. Many visitors could recognize changes in the avatar and link these to Martina’s well-being. For instance, on days when Martina’s biometric data indicated high stress or poor sleep, her avatar visibly reflected these conditions. Some visitors were so attuned to these changes that they contacted Martina to express concern or note positive improvements, highlighting the installation’s ability to foster genuine digital empathy. Furthermore, the project had a profound personal impact on Martina. It provided her with insights into her physical well-being, emphasizing the importance of self-care. This reciprocal relationship was particularly poignant, as Martina felt a compelling need to maintain her health for the sake of her avatar’s appearance, thereby reinforcing the project’s themes of digital-physical hybridity and empathy.

During the creation phase, we found that a practical, hands-on approach significantly improved our results. Using our own recorded material instead of demo videos allowed for a deeper understanding of the system’s capabilities and limitations. Conducting a trial run before recording the final material was essential, as it provided the artist an opportunity to become accustomed to the technology and refine her interaction with it. By engaging directly with the AI and iterating based on tangible results, artists can develop a more intuitive grasp of the system’s potential applications within their creative practice. This approach not only accelerated the development process but also ensured that the final installation was both innovative and deeply personal.

Discussion

The project raises important questions on the connection an artist can make with a digital avatar, highlighting the authenticity and emotional connection that can emerge from this relationship. By linking live biometric data to a digital representation, the project creates an intimate reflection of her physical state that visitors respond to. This connection encourages self-care and underscores the potential for digital avatars to evoke profound emotional engagement. However, as psychologist and author Paul Bloom argues, emotional empathy can be biased and limited. Balancing this with rational compassion ensures a more thoughtful and ethical approach to digital relationships.7

An overview of the different states of Martina’s virtual avatar.

Research in virtual reality has shown that interacting with virtual representations can activate brain regions associated with the sense of agency, such as the insular cortex and angular gyrus.8 This suggests that our AI installation, by providing a responsive virtual entity, may tap into similar neural mechanisms, potentially fostering a sense of embodiment and agency in visitors as they engage with the artwork.

In the Cyborg Manifesto, Haraway argues for a notion of identity that transcends traditional dualisms of mind and body, human and machine, instead promoting an understanding of the deep emotional and empathetic connections people can form with digital entities. This perspective is particularly relevant as the project embodies Haraway’s vision by creating a space where physical well-being directly influences and is mirrored by a digital avatar.

Conclusion

“I’m sorry I made you feel that way” explores the intertwined nature of our physical bodies and digital identities. By connecting Martina Menegon’s physical well-being to her virtual representation, we dissect the delicate balance between self-care and digital embodiment. The installation invites audiences to reflect on the authenticity digital avatars can offer, highlighting the potential for genuine empathy and connection within digital spaces. This connection had a profound impact on Martina as well, encouraging her to adopt healthier habits and reflect deeply on her physical state, knowing it directly influenced her digital avatar.

The open-source Figment tool was crucial in the development of this project, allowing the artist to directly engage with the AI system using her own recorded material. Custom functionalities in Figment enabled the retrieval of real-time health data, establishing the link between the artist’s well-being and her digital avatar. Additionally, Figment was used effectively in an installation context, providing a dynamic and responsive platform for the interactive experience. The tool’s flexibility and user-friendly interface facilitated an iterative approach, empowering artists to explore AI’s potential within their creative practice.

+++

Frederik De Bleser

is a researcher and lecturer at Sint Lucas Antwerp (º1978). His research focuses on the connection between art and technology and the development of free software tools for artificial intelligence and data visualization.

Martina Menegon

is an artist, curator and educator predominantly working with Interactive, Extended Reality and Net Art (º1988). She lives and works in Vienna and teaches at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna.

Lieven Menschaert

is a researcher and lecturer at Sint Lucas Antwerp and LUCA school of arts (º1975). His main interest is in generative and computational design, and he thus sees AI and machine learning as the logical next step in a procedural generation practice.

Noten

- Morningstar, Chip, and F. Randall Farmer. “The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat.” Journal for Virtual Worlds Research, vol. 1, no. 1 (2008), pp. 13–15. ↩

- Rymaszewski, Michael. Second Life: The Official Guide. John Wiley & Sons, 2007. ↩

- Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. London, Hachette UK, 2017. ↩

- O’Rourke, Anne. “Caring About Virtual Pets: An Ethical Interpretation of Tamagotchi.” Animal Issues 2, no. 1 (1998), p. 1. ↩

- Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” The Transgender Studies Reader, New York, Routledge, 2013, pp. 103–18. ↩

- An API, or Application Programming Interface, is a protocol that allows computer programs to communicate with each other. In our case, it connects the data from the smart ring to our own software. ↩

- Bloom, Paul. Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. New York, Penguin Random House, 2017. ↩

- Adamovich, Sergei V., et al. “Sensorimotor Training in Virtual Reality: A Review.” NeuroRehabilitation, vol. 25, no. 1 (2009), p. 32. ↩