This article was part of FORUM+ vol. 27 no. 2, pp. 14-21

The steep slope of Montaña Verde. Participation art, caught between bottom-up principles and top-down policy

Hanka Otte

Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts (ARIA)

In 2018, on the occasion of the Antwerp Baroque Year, Antwerp’s city administration invited the activist architectural collective Recetas Urbanas to create a ‘green’ participatory work in the De Coninck Square. This article analyses the process by which this work, Montaña Verde, was realized. It shows how the project manoeuvred between public and civil space and how this affected the degree and form of participation.

In 2018 nodigde het stadsbestuur van de stad Antwerpen het activistische architectuurcollectief Recetas Urbanas uit om in het kader van het Barokjaar een groen participatief werk te maken op het De Coninckplein. Dit artikel analyseert het proces waarin dit werk, Montaña Verde, tot stand kwam. Het laat zien hoe het project zich manoeuvreerde tussen de openbare en civiele ruimte en hoe dit de mate en wijze van participatie heeft beïnvloed.

Montaña Verde

From 1 June to 25 September 2018, the Antwerp Middelheim Museum featured the exhibition ‘Experience Traps’. In the context of the cultural city festival ‘Antwerp Baroque 2018. Rubens Inspires’ the museum invited sixteen artists to find their own new forms for the aesthetics of the baroque. The result was a number of installations, sculptures, and performances spread out across the sculpture garden of the Middelheim Museum and the city itself. One of these installations, Montaña Verde (Green Mountain), was realized together with Antwerp’s Green Department. In 2015, the Green Department had already been tasked by the city government to realize a flower carpet that year.1 Because of the success of this joint effort, the Green Department again contacted the Middelheim Museum, this time with the request to create a ‘green sculpture’ together. The fact of the matter was that the Green Department wanted to sensitize the urban residents to green in a more sustainable manner than could be achieved with a temporary flower carpet. For the Middelheim Museum, this presented a nice opportunity to reach out to a new public. The museum’s ambition was to involve residents in making their living environment more aesthetic, beyond the museum space, by having them participate in the artwork. The Middelheim Museum and the Green Department advocated, as they eventually together phrased it in the city government’s draft proposal, ‘an organically growing artwork that gives back this small part of the city to its residents and grows as a result of the wishes and input of residents and users’.2 With ‘this small part of the city’ they referred to the De Coninck Square in the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood.

Public and civil space

The goal the city services set themselves was a challenging one, as the De Coninck Square as public space is managed by the district of Antwerp and is therefore the responsibility of the local government. With their idea of ‘giving back this small part of the city to its residents’ the city services entered into a different, namely civil, space. These two domains are frequently used interchangeably in everyday usage, but Pascal Gielen and Philipp Dietachmair point out that there is definitely a difference between public and civil, which in English is expressed in the notions of ‘civic’ and ‘civil’.3 ‘Public’ in the sense of ‘civic’ denotes social spaces that are protected, regulated, legitimized, and perhaps controlled by a government. A public market square thus becomes a civic one when a government determines what can and cannot take place there or when such a governing body installs surveillance cameras to monitor what goes on there. But public institutions that are regulated and perhaps funded by governments are in that sense civic institutions too, such as public libraries, a Prosecutor’s Office, but also state schools or nonprivate museums. By contrast, the civil space refers to the social domain where citizens themselves – either with or without legal status – deploy initiatives. For example, by cleaning up a neighbourhood, organizing a neighbourhood watch, building a school, precisely because a government fails to do so and market parties expect no profits from it. What is also important to the definition of civil space is that those who take initiatives do not know beforehand whether their efforts will be tolerated and perhaps regulated and subsidized by a government. This is because civil actions arise from the fact that people need something and take subsequent action. Whether a government acknowledges this need or not is still undecided at the start of the civil enterprise.

Image 1: *Montaña Verde*, 2018. Fotograaf: Tom Cornille (Middelheimmuseum Antwerpen)

In the case of the intended green sculpture, by ‘giving back this small part of the city’ the responsibility for the square or part thereof was left temporarily to the residents and users. The idea was to realize a participatory green artwork that ‘makes the residents of Antwerp reflect on the meaning, importance, or sense and non-sense of green in the city’.4 The participatory element would mean that residents and users of the square would be involved in thinking about the design of the green sculpture, build and plant it themselves with the help of professionals, and eventually would become its managers. To realize all this, the Middelheim Museum looked for an internationally recognized artist with experience in working with volunteers. Inspired by a lecture given at the University of Antwerp by the Spanish architect Santiago Cirugeda,5 the Middelheim Museum and the Green Department considered his architects’ collective Recetas Urbanas a suitable partner. Recetas Urbanas is best described as a ‘guerrilla’ collective at the intersection of public art and activist architecture. In realizing buildings and constructions together with citizens who need them and can use them under their own management, Recetas Urbanas’s work methods can be described as:

Citizen actions that engender a civil space emancipated from the state (…) as the emancipation of a group that constitutes itself as an active subject capable of engaging with the authorities and disputing their power as a conscious and proactive purposeful citizen.6

This collaboration was an exciting undertaking for all parties involved. As city services, the Middelheim Museum and the Green Department entertained an experiment that would not only operate at the borders between public or civic and civil space but would maybe even cross them. All the more so because Recetas Urbanas explicitly interprets civil space as an a-legal domain where the needs of the user come first, followed by negotiations with governments or market parties to fill these needs. To what extent would the city services be able to hand over the management of the De Coninck Square – now controlled by the city and the district of Antwerp, which both paid a lot of attention to it – to a citizen’s initiative, even if temporarily?7 Recetas Urbanas, on the other hand, by accepting the assignment, would be leaving their familiar domain of the civil space and enter public or civic territory. A public territory which, moreover, was unknown territory for them, as it resorted under a Flemish city administration with other laws and regulations than those in their Spanish hometown of Sevilla.

Participation

In all, a project with multiple players operating from two very different spaces: on the one hand the city services, directed by the city and the district of Antwerp as representatives of public space, and on the other hand Recetas Urbanas together with the residents of the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood as representatives of the civil space. Both spaces have their own logic, which, according to Pascal Gielen, coincide with the logic of different forms of democracy.8 Public space is usually led by the principles of a representative democracy, which is mainly based on ratio. Ratios are well thought-out and it takes time to conceive and implement them. They require rational planning and diplomatic consultations. Within a representative democracy many policies are being developed and implemented top-down, as are regulations and sanctions. In other words, government agencies mainly function with fixed procedures, hierarchic organigrams, and bureaucratic decision-making. All this means that public space embraces a certain slowness. Good planning and fine-tuning imply that alert and especially efficient responses are only possible if events can be seen coming well in advance. The consequence is that the core of the motivation for an action can sometimes be lost.

By contrast, civil space looks more dynamic and more spontaneous. Actions here are swift, as something needs to be done right here and now with the greatest urgency. All civil actions start from an emotion, not from some rational insight or are well-substantiated conviction.9 Civil initiatives are therefore more in line with what Chantal Mouffe calls an ‘agonistic democracy’, one in which emotion and passion, but also religion and beliefs are important building blocks for a democratic environment, even if they are irrational.10 Mouffe’s view, like that of Jacques Rancière, is that democracy can also be founded on dissensus or unresolved conflicts and that radically different social groups (on the basis of ideology, religion, identity, or social class) can live side-by-side just as well.11

However, just because civil actions often begin with an emotional spark doesn’t mean that they are without ratio. Those who organize civil actions must after all channel the initial emotions through reflection and communication.12 This is where the logic of a discussion democracy comes in handy, once described by Jürgen Habermas as a societal playing field where consensus is reached by consultation and rational arguments.13 Still, emotion and passion remain the driving force of the organization and also determine the usefulness or mission of such civil structures. Obviously, the logic of public space is pretty much diametrically opposed to this. It is not just that the distance to the core of the problem (the immediate cause of a civil action) is greater in a representative democracy. Citizens themselves are more at a distance too, as they are not only represented by a political governing body, but also by an executive civil service. It is therefore harder for them to exert any direct influence, which is not conducive for their willingness to participate. This means that public space is farther removed from citizens than civil space in multiple ways, a feeling that citizens may have despite the fact that they physically move in that public space. And this is exactly what happened in the Montaña Verde project, with all the consequences for the level of participation by residents and users of the De Coninck Square.

‘Bad weed’

Both the renewed realization of a flower carpet and sensitizing the Antwerp residents for city green were seen as ‘urgent’. The first urgency stemmed from a great enthusiasm about the festive and colourful flower carpet created by Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven on the Grote Markt square in Antwerp in 2015, which generated much attention from tourists, the media, and the residents of Antwerp themselves. The second urgency undoubtedly had to do with the election programme of some political parties. However, by the time the Green Department thought it feasible to combine both tasks in one project and approached the Middelheim Museum to take care of the artistic component, almost two years had passed. Therefore, there was ample time to think about a different, more sustainable form of flower carpet. And after such a long time the sense of urgency for ‘more green’ will probably have subsided for most of the electorate. Moreover, it remains to be seen whether the choices made by the Green Department (of course with a mandate from the city administration) still coincided with the needs of the electorate of that time. For one thing, it was unclear where the people who voted for ‘more green’ were living.

The choice for De Coninck Square as the place for the green sculpture was not the result of a direct request by residents and users of the square either. The Green Department had made a list of various ‘greying’ (i.e. non-green) places in the city that were at the same time accessible for tourists and – together with staff members of the Middelheim Museum, Recetas Urbanas, and even researchers from the Antwerp University – took it upon themselves to choose the most suitable site. The De Coninck Square met all these conditions: it was ‘grey’, could be easily reached by tourists and, not unimportant: it was an interesting place for the social architecture of Recetas Urbanas. Without having met the residents and users of the De Coninck Square, Cirugeda sensed what this square might need and in a creative manner he made the link between the needs of this part of town and the wish for more green:

The huge challenge for cities is to bring extremely different people to live in and share the same environment and to design this environment for all. Obviously, there will be some left behind. Because they are too different, not ‘adapted’ or ‘integrated’, sick or lost… they are considered as the ‘bad weed’ of urban life. Yet, everyone has a right to the city, to participate in city life and the city’s development. … If we want to rethink how we build and live in our cities, it is crucial to include those who are excluded now. Let’s use this moment to grow social links as much as green; to re-introduce bad weed and wild weed, by changing the way we look at them.14

This first attempt by Recetas Urbanas to use the metaphor of ‘bad weed’ to direct attention to perhaps more urgent problems around the square and placing these on the agenda according to the principles of an agonistic and/or discussion democracy, didn’t make it, though. Instead of ill weeds, types of plants were chosen that were cultivated and used for their nutritious or healing qualities at the time of the Baroque, which was after all the theme of the exhibition for which the work was produced. This ‘safer’ choice marks a moment that would prove crucial for the subsequent progress of the project. In fact, this one group of users of the square, the ‘bad weed’, was, at least indirectly, not acknowledged from the very start. In the opinion of the director of the Green Department the project had to be as politically neutral as possible. A position that is very fitting for the public space, where political decisions are made by the city council – which after all represents the citizens – and where civil servants are not supposed to show any political preferences but to swim with the political tide. It is also a position that limits the civil space, whereas the original intention had been to use this project to explore that civil space.

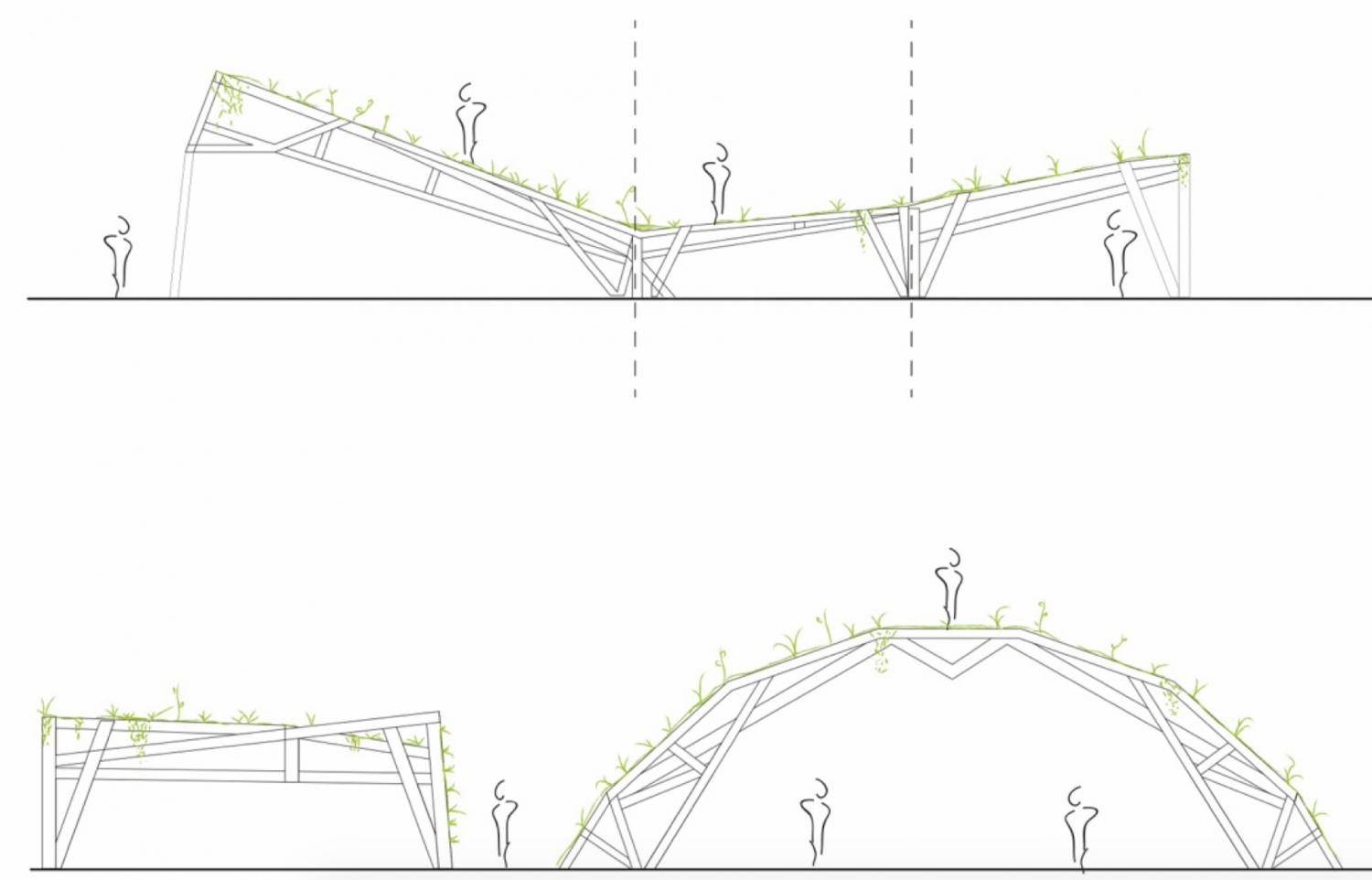

Image 2: *Montaña Verde*, 2018, schetsontwerp. Recetas Urbanas.

At the same time the choice was made to use herbs and fruit trees in the green sculpture, another choice was made as well, albeit less consciously. The remarkable fact is that from the very moment Recetas Urbanas had shown the first sketches of a possible sculpture in their project proposal, this design remained more or less unchanged. It is clearly recognizable in the final work, whereas the intention was to involve residents and users of the De Coninck Square and all other interested parties in thinking about the sculpture and help design it. The work would thus be created from the wishes and needs of the participants and would therefore look completely different from these first sketches, Recetas Urbanas promised. However, in the communication inviting potential participants to join the project, the design was consistently shown from the very beginning. Although those present at the information meeting of 7 March 2018 had participated in thinking about and sketching the design, the initially presented sketches remained the basis for the sculpture and this image became a permanent fixture in the process (see image 1).

The design would later be elaborated by students of the School for Architecture and the design of the green roof was left to employees of the Green Department, but all this was done within an already established framework:

We were asked to think about the content. I found that quite challenging, and the theme was the Baroque Year. So that’s what we worked on, that’s what I started thinking about. And so we thought of these tiles. I was thinking of the tiled floor of the chapel in the Rubens house. Eventually, this became a design, which then ended up on the roof, with the plant species that came from the Rubens garden.15

All this while the project was specifically intended for the residents and users of the De Coninck Square. But before even a single resident could have a say in how the work would finally look and what it might mean for the square and the neighbourhood, ideas had already been worked out and numerous decisions had already been made by others. During several consultation rounds between the Green Department, the Middelheim Museum, Recetas Urbanas, the Permeke library, neighbourhood sports and citizen participation of the district of Antwerp, the material and plants were decided upon, as these had to be ordered long in advance. Machines and other necessary tools were bought or booked, man-hours were planned, and decisions were taken with regard to safety (the storage facilities, the safety of the construction, insurance, permits, and so on). They also thought about activities that might take place and what people could be called upon to organize them. Among the people holding these meetings there was only one resident, a freelancer who was responsible for involving as many residents as possible in the project. And only one person, an employee of the Permeke library, had a direct involvement with the square, as the library is located there and often organizes activities in the square. All the others were there ‘on behalf of’ the residents and, moreover, everyone at the table was either directly or indirectly employed by the government, including Recetas Urbanas as contractor. In brief, the preparation phase, which lasted almost eleven months, took place exclusively within and according to the logic of the public space.

Fences

This would change as soon as Recetas Urbanas took up residence in the De Coninck Square. Starting in the second half of April 2018, using heavy equipment, the Green Department brought large pieces of wood to the square and construction began. The work in progress literally became part of the square, but did that also make it part of the civil space? For security reasons, during the construction phase the site was cordoned off with fences, which provided the Middelheim Museum with the opportunity to hang up large information boards. By doing this the museum appropriated part of the square, as it were, branding the site as a separate space. All the more so since in the texts on the boards a distinction was made between the part of the De Coninck Square inside and the space outside the fences by using the word ‘they’ (the Middelheim Museum, the Green Department, Recetas Urbanas, and volunteers) and not ‘we’. The information boards were designed in such a way that it was immediately clear that this was a project of the city of Antwerp. A project in which the logic of the public space was leading, starting with the communication house style (see images 2 and 3).

Recetas Urbanas attempted to break through the fences and to let in the civil space. In their collaboration with the city services this was visible in several ways. For example, unlike the civil servants involved, the people from Recetas Urbanas were also present in the square outside of regular office hours. Not just to realize the artwork, but also to be part of the neighbourhood by making optimal use of the space and, together with volunteers and preferably also other residents, have meals there, drink, talk, make music, and party. Starting from the notion to make public or civic space civil again, social time is of great importance to Recetas Urbanas. However, the permit to use the square for seven months to create an artwork for the ‘Experience Traps’ exhibition was not a licence for the construction team to build outside the agreed terms or party there outside the permitted hours. One evening, the police even told the construction crew to end a party they were having with the volunteers to celebrate the conclusion of one of the building phases and ordered them to leave the square. Although the short lines of communication with (and obliging attitude of) the Green Department meant that swift action could be taken when something needed to be done that was not covered by the permit – such as removing a fixed bicycle stand – Recetas Urbanas’s manoeuvring space was limited by the rules and regulations that governed the square. In other words, the square was basically treated as belonging to a space of law, regulation, and concomitant bureaucracy.

Professional versus social time

At several moments there was tension between searching for the civil space and the persistence of the public space. For the Green Department, working according to a plan is very important for organizing the work and therefore the number of man-hours available for any project is fixed. This also applies to the Middelheim Museum and the freelancers the museum hired to help make the project go smoothly. This professional time management frequently clashed with the more organic or, in Cirugeda’s words, ‘informal’ work method of Recetas Urbanas. This meant that the builders of the architectural group were not working fixed hours, that there were frequent changes in the plans (also with regard to materials that were needed), and that it was sometimes spontaneously decided not to work on a given day, even though volunteers coming from the Netherlands were scheduled to come and help. This frequently led to irritation on both sides: with the employees of the Green Department and the Middelheim Museum, because it demanded greater flexibility and extra efforts, but also with the people of Recetas Urbanas, who could not always count on getting help, especially not outside office hours or when the number of man-hours in the budget ran out. This tension was strongly felt by the two freelancers, both of whom had a mediating role between these two actors with such a different attitude to time. One of these freelancers was hired as a production assistant and mediated between the financial service of the city administration (which controlled 70 percent of the overall project budget) and Recetas Urbanas:

They [the city of Antwerp] need weeks to approve any document. So, I was pushing and pulling all the time. Decide now, right now, because otherwise the city can’t order it in time. But then he [Cirugeda] suddenly decided that he wanted something altogether different. It was a very problematic combination with this top-down approach. The City of Antwerp wants everything documented and approved by three committees if someone wants to have three screws. Santi [Santiago] and his people kept changing the design while they were already building it and would spend more money than the budget allowed for. Then the city would tell me that they were already over the budget. I was a nobody in this project.16

The other freelancer was hired by the Middelheim Museum to involve the neighbourhood in the project. He was experienced as a process facilitator, connecting people around social projects and this, combined with the fact that he himself lived in the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood, made him ideal for the job. However, these various identities also complicated his role. For instance, he saw it as problematic to invest his private time in the project in addition to his professional time, something which he did ask other residents to do on behalf of his client. All neighbourhood residents were expected to support the project as volunteers. After all, it was being built for them, wasn’t it? But that was exactly the problem. While a whole bunch of people who were not living in the neighbourhood were being paid to realize the work on the square, the residents were expected to lend a hand without being paid. After all, they were given a nice green construction in return. However, this principle of reciprocity doesn’t work when residents haven’t asked for it themselves and thus, in other words, have no vested interest in it.

Civil interest

That some did develop an interest in the construction became apparent in the four months that Montaña Verde adorned the square, providing a pleasant, shadowy place to sit during the very hot summer. That it also turned out to be a perfect spot outside the range of surveillance cameras for drug users, did not fit the civic picture. But that could also be said for the residents who were expected to voluntarily water the plants and harvest the herbs, which demanded quite a lot of time, not to mention discipline. All the more so, since the lack of green was not high on the list of the neighbourhood’s concerns. If it were up to the residents, business owners, and other users of the square, getting rid of the traffic across the De Coninck Square was more of a priority. The through street that runs along the square has been a thorn in their flesh for many years.

The wish to free the entire square of traffic is quite strong. However, I don’t see this happening, since it is on the axis of emergency traffic towards the hospital and is also used by public transport. But it is a wish that has been there for many years, getting rid of the traffic.17

The issue did come up during the construction of the work, but the design and concept were already in a far too advanced stage for the project to reflect on this feeling or express it. Therefore, there was little motivation to find room for agonism or discussion with regard to this matter.

During the construction of Montaña Verde another, not unrelated interest of residents came to light. One volunteer, who represented the African community in the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood, asked Recetas Urbanas if it was possible to create a safe playground for children, along with the construction. However, this wish not only went against the interests of the local governments, but also against those of a private owner who refused to entertain the idea of making a piece of wasteland property temporarily available for this purpose. These are issues that Recetas Urbanas normally doesn’t shy away from, but now, as contractor of the city of Antwerp and completely embedded in the structure of the public space, the group had no leeway to address these issues. Neither the politicians nor the residents and users of the square could be reached directly, as they were represented by professionals: civil servants and the freelancers they had hired, all of whom did not follow the rhythm of the residents and users of the square but of the rules and laws of their employer. For Cirugeda, this presented a huge problem:

(…) The question is, are they [the city services] fighting for the others. … The problem for the De Coninck Square neighbourhood is with the Social Department, with the Green Department, with the Educational Department and all of them. … They never appear[ed] to try to give solution to the neighbourhood.18

There was hardly any manoeuvring space to really address questions raised by residents, or even have a discussion about such questions. On the one hand, it was impossible for Cirugeda to contact politicians directly, which meant he couldn’t achieve the right negotiating position, for example to plead for extension of the period during which the construction would be in the square: ‘I don’t even know where the building of the district [of Antwerp] is.’19

Image 3: *Montaña Verde*, 2018. Fotograaf: Tom Cornille (Middelheimmuseum Antwerpen)

On the other hand, it proved to be difficult for Recetas Urbanas to establish a relationship with residents and users of the square. This was partly due to the fact that the builders themselves were not residents of Antwerp. Both the geographical and ‘cultural’ distance worked against the project. Sevilla, the Spanish hometown of Recetas Urbanas, is not exactly around the corner and the budget did not allow for the architects to remain in Antwerp for a longer period. The Middelheim Museum thought they could solve this problem by hiring the already mentioned freelancer. However, this person – although he had an extensive but formal network and ample experience, but again only in formal circles – also invoked the logic of representative democracy. As process facilitator he did not succeed in reaching the core of the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood. At the information meeting he had organized with the aim of recruiting volunteers, half of those present were professionally involved with either the neighbourhood or the project. And of the 95 people who registered to help build Montaña Verde, in the end only 25 volunteers from the neighbourhood itself helped out, of which only five for more than four days.

This continuously going around in circles in the municipal networks and entertaining collaborations with professionals led to conflicts with the people of Recetas Urbanas, who, by contrast, wanted to be in direct contact with the residents. So, the project did cause conflicts, but not of the kind nor on the level at which they can contribute to an agonistic democracy.

In addition, the ‘negligence’ of people who had registered to help (why stay away if you have registered?) surprised and irritated the people of Recetas Urbanas. This irritation only grew by the end of the project period, at the time that the work was dismantled and the material was distributed among those interested. The people of Recetas Urbanas were not exactly charmed by the trouble it apparently took to distribute the wood and the tools that were available for free.

In Sevilla, people would stand in line for it. … Of course, I don’t want to spend … more time in the city that is not mine, where really the problem [is] that people are very… sometimes, very comfortable.20

Contradictio in terminis

It is obvious that during the entire Montaña Verde project the rhythm of the public space of the representative democracy prevailed over the rhythm of the civil space and thus the participation of citizens was limited. Not just in the sense of the number of residents and users of the De Coninck Square that eventually took part – which was by no means a representation of the inhabitants of the Amandus-Atheneum neighbourhood21 – but most of all in the manner of their participation. Children (195 in all) from schools in the neighbourhood were given the opportunity to place and fill flower boxes during half a school day. The volunteers mainly learned how to work with large materials and big machines but were told exactly what to do and the builders had clear instructions. Here and there a resident would add something to the construction: an imitation pigeon on the roof or a drawing burned into the wood. Or soup would be served by local residents. One of the volunteers who was active on the site almost daily, later said that he got a lot of satisfaction from being allowed to work on something this grand, but also from distributing the many herbs to the local residents. But that’s about as far as participation went, let alone that emotions collectively shared by the neighbourhood were addressed or openly debated. The search ‘for models of involvement and participation in order to explore together with the residents if and how more green may contribute to the quality of the city’ never materialized.22 Other, perhaps more urgent issues did briefly surface, but never led to a political debate. At the moment when volunteers from the neighbourhood were recruited, the plans were already in an advanced stage, so there was no room for making an artwork that would touch upon sensitive issues and reflect upon the ins and outs of the square. The small group of local residents who maintained the green during the summer disbanded as soon as spraying was banned in the city because of the water shortage in this very dry season. Some called for keeping the work in the square permanently, but again it turned out that the initiator, the freelancer from the neighbourhood, didn’t have enough support to be able to convince the district of Antwerp.

In other words, the initial idea to realize the green sculpture in the De Coninck Square in a bottom-up manner and thus explore the civil space by organizing an intense open debate with room for emotions and conflict, was frustrated by the top-down management that strictly adhered to the principles of representative democracy. The slope of Montaña Verde thus became a very steep one, something the Middelheim Museum also was aware of, in hindsight:

(…) In fact, it is a … contradiction in terms that there is a sort of top-down decision like: we are going to do a sustainable, green intervention in a neighbourhood … with a bottom-up collective. … [F]or me, ‘Experience Traps’ was … Very much about control. So about how people try to gain control over their environment, over the beholder; how an artist tries to control our expectations. And yes … It is in fact a little bit strange; is this a form of control over a, let’s say, socially difficult neighbourhood that the city government is practising? Or not? … as a curator one obviously feels that there is friction here.23

+++

Hanka Otte

is a postdoctoral researcher on cultural policy at the University of Antwerp, Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts (ARIA), where she is part of the Cultural Commons Quest Office (CCQO) research group. Her research focuses on which conditions are needed for a balanced artistic biotope, and how policy can help generate creative commons.

Footnotes

- In the summer of 2015, Belgian visual artist Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven, under the auspices of the Middelheim Museum and in collaboration with the Green Department, realized the flower carpet Flower-Power in the Grote Markt square for a period of ten days. ↩

- City of Antwerp, Draft Proposal, 2 February 2018. ↩

- Gielen, Pascal and Philipp Dietachmair. ‘Public, Civil and Civic Spaces’, in The Art of Civil Action. Political Space and Cultural Dissent, ed. by Philipp Dietachmair and Pascal Gielen, Valiz, 2017, pp. 15-18. ↩

- Email from the Director of the Middelheim Museum, dated 22 May 2017. ↩

- Seminar ‘Artistic Constitutions of the Common City’, organized by the Antwerp Institute for the Arts, University of Antwerp, 21 and 22 April 2017. ↩

- Bonet, Llorenç. ‘Recetas Urbanas: urban recipes for an active citizenry’, Dietachmair and Gielen, ibid., p. 166. ↩

- For example, in 2003 the Permeke city library was established in the square, various development projects were implemented and police surveillance increased, by means of surveillance cameras and other measures. ↩

- Gielen, Pascal. ‘Cultuursector, staak!’ De Standaard, 13 November 2019, www.standaard.be, accessed on 13 January 2020. ↩

- Castells, Manuel. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, Polity Press, 2015. ↩

- Mouffe, Chantal. On the Political. London/New York, Routledge, 2005. ↩

- Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Bloomsbury, 2015. ↩

- Gielen, Pascal and Thijs Lijster. ‘The Civil Potency of a Singular Experience. On the Role of Cultural Organizations in Transnational Civil Undertakings.’ Dietachmair and Gielen, p. 40. ↩

- Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press, 1989. ↩

- Recetas Urbanas, project proposal, October 2018. ↩

- From an interview with an employee of the Green Department, 2018. ↩

- From an interview with the freelance production assistant, 2018. ↩

- From an interview with an employee of the Permeke library, 2018. ↩

- From an interview with Santiago Cirugeda, 2018. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Of the 95 people who registered, in the end only 25 volunteers from the neighbourhood itself or form other parts in the city participated. Looking at the names (22 Dutch/Belgian names) and based on the observation of both the information meetings and on-site, the individual volunteers were for the main part white (Belgian and Dutch) people. Keeping in mind that the neighbourhood consists for 70 percent of people with a migrant background, only a small portion of the neighbourhood was represented. ↩

- Herman, Laura and Pieter Boons. Experience Traps, catalogue for the exhibition ‘Experience Traps’ from 1 June to 28 September 2018. Moto Books, 2018, p. 91. ↩

- From an interview with one of the curators of the ‘Experience Traps’ exhibition, 2018. ↩