Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 28 nr. 3, pp. 52-63

‘Sieraden, materie, tijd: de ware kost van een juweel’. Een weg doorheen sociale contexten, op zoek naar de ware kost van een sieraad.

Saskia Van der Gucht, Irma Földényi

‘Jewellery, Matter, Time: True Cost of a Jewel’ focuses on the social contexts of mined precious materials – contexts of production, trade, collections, wearers – to trace the true cost of jewellery. The invisible impact of industry in fashion, design, and architecture is increasingly gaining attention as a theme. Taking the Anthropocene as an overarching framework, we ask ourselves: What are the roles of a jeweller in this era?

‘Sieraden, materie, tijd: de ware kost van een juweel’ focust op de sociale contexten van de kostbare metalen die we uit de aarde opdiepen – contexten die te maken hebben met productie, handel, collecties, en het dragen van juwelen – om zo de ware kost van sieraden te achterhalen. De onzichtbare impact van de industrie op mode, design en architectuur wint meer en meer aan belang als thema. De auteurs gebruiken het Antropoceen als overkoepelend kader en vragen zich af: welke rollen vervult een juwelier vandaag de dag?

Irma Földényi:

The current research starts from the practice of mining. Mining is an example of geo-engineering that is changing the surface of the earth, an activity that happens underneath our feet, but also as a practice that is at the heart of jewellery production. We started to explore how we can trace materials back to their source to make the true cost of jewellery visible. What we are doing now is mostly questioning the conditions of our research: What does it mean to trace a material, what kinds of materials are being used, how do we read what we find, and how do we bring it back into a context of artistic research and jewellery?

The road being long

Petra Van Brabandt:

Your research is about acquiring critical knowledge to bring back to a jewellery context. You are making this journey, tracing the cost, tracing back the origin of materials used in the field of jewellery. Where has this road back taken you so far?

S 4.29.1-2 IF

S 4.29.1-1 IF

S 4.29.1-3 IF

S 4.29.1-4 IF

S 4.29.1-5 IF

Saskia Van der Gucht:

At times it feels like a long journey, because we end up in a context that is industrial and commercial. At the same time, we encounter some familiar references. The research has all these elements that we know about, certain aesthetics and ways of displaying, but also stock market prices, gemstone fairs, the gold rate; aspects that are all connected to global economics. It is interesting to see this hyper-commercial context in between the industry of mining and our artistic field. In a way, this commercial jewellery world feels very familiar to us, but at the same time we don’t speak its language, and it lacks a certain criticalness that we could relate to, because it is not critical of itself.

IF: When we looked into the mining process of the gemstone tourmaline, for instance, we found an article in the Guardian that traced the stone and its journey to the wellness industry.1 The crystals are used as a filter to allegedly heal water in a reusable drinking bottle. The interviewer asked a salesperson if they knew where the stones came from, and they replied that they would love to know but that tracing back its origins would be too costly.

SVdG: In that same article we also read about tourmaline mining in Madagascar. A salesperson who operates between big buyers from the United States and small artisanal miners who dig for the stones, said that these two worlds are so different that they would never be able to understand each other; there is no way of bringing them together and making them speak the same language. At the same time, he is just one man in between who does the work and translates as he goes.

Stories such as these leave us with uncomfortable questions that commercial companies were not being asked until recently.

PvB: It makes me think of the work of Gloria Wekker who talks about white innocence; she says that from a position of white privilege you have no reason to look for knowledge on racism. On the contrary, this knowledge would make you question your position, and therefore your comfort. The miners are there, the market is there, the consumers too. They can keep going about their business without asking these questions. Doing things differently would endanger their ignorance, and therefore their innocence, and indeed their comfortable position.

Gold

PvB: Gold, next to diamond, is the most well-known material in the commercial jewellery world. Do you in your artistic practice or do other contemporary jewellery designers still work with gold?

SVdG: They certainly do. It is the most malleable metal in the world; that’s one of the reasons why it is so precious and the most important reason why it is used in craft and design all throughout history and across different cultures. The oldest processed gold we know of is Bulgaria’s Varna Gold Treasure – golden bracelets and a breastplate were found in 1972 – that dates back as far as 4400-4100 BCE. Whenever this malleableness is expressed in numbers, it becomes very interesting. For instance, one ounce of gold, which weighs 28 grams and is about the size of a small coin, can be stretched out into a thin sheet of nine square metres.

Different languages

IF: Because of the physical and chemical characteristics of the material, there is the language of gold itself, but there is also a formalistic language in jewellery that often has nothing to do with the material qualities. In the normative design formats of gold, the unique qualities of the material are disregarded, which brings about an alienating feeling. Not only gold’s unique material characteristics, but also its origin is visually ignored in such designs. The beauty of gold when it is freshly unearthed, for instance, is being ignored. We are interested in questioning how to show these material qualities and visual origins and bring them back into the design of a jewel.

PvB: The language of gold as a material and as a mined resource is far removed from the visual language of gold jewellery as a commodity. The material and visual relation between both languages is absent. Do you know why?

SVdG: There might be two explanations for this. Firstly, it might be related to the long history of gold as a material for goldsmithing. This craftsmanship has been around for so many centuries, perhaps it carries the burden of time and made us forget that gold actually comes from inside the earth and that we extract it in a harmful way. At a certain point in history, humans made a global agreement that this was one of the most valuable materials in the world. Because there was quite a large supply, people used it as a currency with its first uses dating as far back as the Late Period (sixth century BCE) in Ancient Egypt. Secondly, gold has a specific visual language. It is a very recognizable material through its colour and light reflection. It doesn’t corrode or tarnish, because it doesn’t react to water or air, so the shimmer and shine stay throughout time.

PvB: Its language cannot be mistaken, the signifier and its meaning seem to be one. Its high value and attractiveness seem to reside in its appearance. The fact that gold has such a high value also confirms what you referred to earlier: its extraction is harmful. It makes sense that behind such high value, effort and pain must be hidden.

IF: Then we come to the question: What were the reasons that gold was mined?

There is more demand for its value than its physical characteristics and ways of sourcing gold in jewellery need to be continuously reassessed. Especially now that most of the gold is outside of the earth’s crust and in circulation.

PvB: Seeing gold is desiring to touch it, to grasp it, to hold it closely to the body, to keep looking at it. Gold is in this sense like sugar, another colonial material. Can you tell us more about the extraction history of gold?

SVdG: There are different significant moments in its history. Big industrial mining needs to be done with a lot of machinery and results in fascinating structures; modern open pit mines like the Grasberg mine in Indonesia. But the way gold was formed and is embedded in the earth enables different ways of finding it. There is, for instance, a lot of gold found in rivers and lakes. Throughout history, there were different gold rushes in North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Brazil; most of them at the end of the nineteenth century. In a way, finding gold was accessible, but that is also what’s troubling about it. Part of the myth of the colonial American dream is built on these stories. It is the myth of the land where the poor white man could find his fortune – ignoring and uprooting the layered meanings and the complex social relations these lands, rivers, and materials have for the indigenous populations.

As a more recent example, in the 2016 AFRASO documentary by researcher Diderot Nguepjouo, and filmmakers Katja Becker and Jonathan Happ on small-scale mining by Chinese companies in Cameroon,2 the independent Chinese contractors bring machinery and tools that most of the local population cannot afford; they dig through the earth and the sand gets washed and filtered for gold. Afterwards, people from the local community are allowed to sieve through the sand again to look for scraps of gold that are too small to be picked up with machinery.

So there is a sort of hierarchy, from the land owned by the government, making deals with foreign contractors who bring machines, and then the washed sand gets passed down to the people. On a good day they might find enough gold to make ends meet for that day.

IF: An entirely different way of organization and use of technology is found in urban mining: for the postponed 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, the gold medals were made out of recycled gold. It was a multi-year project to develop a completely new infrastructure in Tokyo for collecting electrical devices, which provided enough gold to produce the medals.

With this whole process, somehow jewellery and urban infrastructure found a connection.

Different research languages

PvB: At the start of this conversation, we mentioned the difficulties of bringing back the findings on tracing materials to a jewellery design context. Different languages meet each other: the industrial language, the symbolic languages of jewellery, the design language. You work together on this research project, but you come from different practices and speak different languages, artistically but also literally. How do you meet each other language-wise in research?

IF: When we meet, we always start a conversation by looking at objects, photos, films etc. We developed similar curiosity-driven and associative research practices. Our visual languages differ in what we do with our research findings. As we started translating the research into visual work, we found out that we have different approaches in the context of design and art. This was paired with a lot of learning, experimenting, and teaching each other to become familiar with each other’s languages. And that brings on a stronger collaboration.

S 4.29.1-6 IF

PvB: What are the different languages you employ to share this research with one another?

IF: Personally, I inherited from the design protocols that the priority lies with both my intentions and the audience. What drew me closer to jewellery is that it is an easily understood format to use as a critical medium. I could never make an ornament for the sake of its beauty. I always start with historical, economic, political, and material investigations, and develop them into an inviting object. I am very selective with the references that I build upon and how I show the links between references. Making jewellery is also a context where the maker’s decisions can run fast without pushing through a managerial system; therefore, it is literally and metaphorically in my hands. This freedom I have in jewellery is surrounded with a discipline I have, which is to make objects for critical reflection, transparency, or clarity and to approach people in a simple way. That is certainly why I am also working with this research trajectory of true costs.

SVdG: The concept of jewellery for me is much more a source of inspiration than a medium or an outcome. The way I look at things, my vision of the world is a made-up framework, it operates as a piece of fertile soil, filled with images, themes, materials, and references.

Jewellery is one of them, with its specific language on preciousness. I’m very interested in these concepts of emotional and economic value. When I’m making work, I start off with certain elements, but I’m always searching for the core of things. How can I make something that goes back to its essential elements, that bears its meaning in itself? What’s the shape or the material an object needs to be to be able to communicate its essence? So, there is this idea of full autonomy, not just for the work itself, having to be able to hold its own, but also for the way of working, which is a very individual process.

Language and probe making

PvB: How do you translate your artistic language to each other? Very practically, is it through talking and listening?

SVdG: I think a big part of the research project is us having conversations. We have weekly meetings, where we talk about everything that we’ve found and made and read. At a certain point, we started to make small presentations for each other. A week would go by, and we would visually organize everything that happened while trying to map out our thought processes. In the first phase, we were doing a lot of reading and then, at a certain point, we decided we wanted to start making things, even though they weren’t finished pieces or products and we hadn’t come to any conclusions yet. We wanted to have a go at thinking through making. It helps us connect things. The probe-making helps us with translating, incorporating, and processing information into something physical.

S 4.29.2-1 SVdG

S 4.29.2-2 SVdG

S 4.29.2-3 SVdG

IF: Probing is a practice-based research method that we developed to identify and visualize relationships between material mining and their social contexts in the jewellery industry. We do this to understand the unclear and sometimes conflicting connections between jewellery and its materiality.

We first select three elements from three different categories. A list of mined materials, theoretical texts and articles on the Anthropocene, and the role of a designer, artist, jeweller, teacher, etc. The making and visualizing happens intuitively by processing the theoretical text, stepping into a role, and working with one material. These three elements are interchangeable with all texts, roles, and materials that we include in an incomplete index.

These probes are visual notes to materialize research into an outcome. They are not illustrations, but rather translations and a way of processing information; not just for us, but also to be able to communicate with others. They are visuals, objects, maps that create food for thought before concluding the research in its final form. They are tools for thinking-with and building-upon.

Sand

PvB: Can you give an example?

IF: In the sand probe, we both started with the same literature, the text Surface Visions by Tim Ingold and the mining of sand.3 For me, it was very important to step into a context outside my workplace, a context that I didn’t control. I chose to do fieldwork at Maasvlakte, which is land reclaimed from the North Sea and serves as an industrial facility within the harbour of Rotterdam. This particular sand of the Maasvlakte has its own history: it was brought from the North Sea to fill up the water to make land.

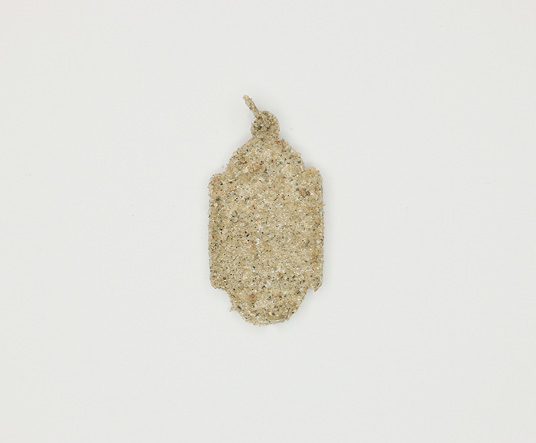

By spraying industrial amounts of sand, land is created – which results in a soft, flat, wavy surface. I played with this technique on a small scale by applying sand layers onto medallions, an archetype in jewellery. The imprints of the jewellery surface started to fade away, and only the outside contour of the pieces remained recognizable. With these probes I was looking for connections between geo-location, sand, and jewellery.

SVdG: I was searching for a way to translate Ingold’s idea of paying attention to surfaces, and ways of treating them, as primary conditions for the generation of meaning, into one object. How could I do this without coming up with unnecessary, decorative decisions? I wanted to let the material be what it is in its clearest form.

When you make something, there is a design and a construction, which I tried to essentialize in this piece. I took a standard size A4-sheet and I made a balsa wooden box of one centimetre high. I filled it up with sand to create a surface that could be interacted with. I made small wooden tools that accompany the A4-surface and that you can use to draw in the sand. The tools are ambiguous, as they are derived from existing tools but reshaped and sanded as if they might have been found somewhere, worn down by erosion, but still partly recognizable.

G 2.1.2-1 SVdG

Gold probes

PvB: I was also intrigued by your two gold probes and I’m interested in hearing about this work.

SVdG: I was researching platinum and gold mining and fell down an internet rabbit hole that led me to a cryptic video on YouTube that only had thirteen views. It felt like I found this rare gem, being the fourteenth person to watch this video. It was called ‘Jim Paterson on the potential at the Pedra Branca project’ and it shows a CEO of Canada’s biggest metal mining company ValOre.4 Jim explains how they recently bought the Pedra Branca project, a piece of land in Brazil. It is a public video, but it’s clearly directed towards a very specific type of audience of shareholders and people of interest.

By transcribing the audio of the video into written text, I created a strange kind of poetry. I did the opposite with the Excel sheet drawings: I took out all of the information of an online data collecting page from ValOre, and only used the visual language of the framework. I made a series of drawings in Excel, and distorted the images afterwards with photo-editing software meant to be used for touch-ups and for smoothing out surfaces. The text and the drawing complement each other: they both come from a commercial industrial world and then shape-shift into an artistic abstraction.

G 2.1.2-2 SVdG

PvB: This ‘poem’ spoke to me in a way opposite to what you would expect of such a company. It’s almost non-performative, unlike a TED-talk or a pitch. It carries a violent and demeaning tone and has this boy scouts’ attitude to it. It also adopts the colonizer’s language of taking land without valuing it for what it means.

SVdG: Exactly, it is really this clear and uncomfortable language that draws my attention.

PvB: Also, the title is significant: ‘Jim on the Project’. The material doesn’t get named in the poem, which is a very telling silence. Irma, in what way did you work with this gold probe?

IF: I found a graph on gold recycling from electrical waste based on the research published by the UN Global Waste Monitor 2020.5 I wondered how I could create an intuitive connection to this information. How can viewers feel a certain ownership, an emotional link, when reading numbers and graphs and their underlying reality? It’s a way of embodying data on consumption of electronics, their afterlife, and the value of gold, which doesn’t change, although it has been used and shaped in extremely different contexts. Beyond the numbers, these graphs also show which countries can create the conditions for recycling.

PvB: Indeed, what stands out in the graph is how Northern Europe occupies the first and Africa the last position. It shows the relation between what belongs to whom and who is profiting from whose resources and labour. In a very direct way, you made this visible. Who creates waste electronics, who has the right conditions to recycle it, and therefore profits a second time from the resource?

Power structures

PvB: How these power relations define value is one of the main domains of inquiry in relation to the challenges of the Anthropocene.

IF: A clear example is a company called Fine Minerals International, which specializes in buying crystals for high-end collectors. The collections are displayed in CEO offices and executive rooms; they represent a form of power but are never literally framed as such. This visual norm that you are in power if you can surround yourself with valuable objects often figures into the commercial jewellery field. When I look at the image, the first feeling I have is that the room is suppressive without critical reflection.

What is strange is that these stones actually don’t have a naturally high value; it’s human contracts that agreed upon the value. When, for example, the tourmaline stones were taken out of the ground, they were worth a cup of rice.

G 2.1.1-1 IF

Gold recycling. Electrical Waste Recycling % 2019. Source: UN Global E-waste Monitor 2020

G 2.1.1-2 IF

Gold recycling. Electrical Waste Growth % per year. Source: UN Global E-waste Monitor 2020

SVdG: The idea of value and of putting a price on something is always an agreement between people. At a certain point, market prices became a complicated, intricate system of things depending on each other. This causes the illusion that certain things are valued by the laws of nature. But the fact that there is such a big difference between the price for which the crystal had been sold and bought, and the cost at which it was taken from the land, is after all so hard to make sense of.

PvB: At some point, the material loses its value if you trace it back to its free existence under the surface. The closer you get to mining, the lower the economic value. The miners are written out of the story of high value. High value does not seem to start at the beginning. This seems to be the crucial essence and problem of the Anthropocene.

IF: The question of value remains very interesting to me, as it is such an economic way of speaking, seemingly foreign to our artistic relation to the material. Trying to understand that language is where discomfort and curiosity start.

SVdG: The way the crystals are displayed reminds me of a natural history museum and how artefacts from different cultures are displayed in Western museums, which is problematic because it is rooted in colonialism. In our work, we want to be very honest, and create space for uncomfortable feelings without being biased, accusing, or outraged. We are searching for a way to use language to make space and show injustice without this being the sole purpose of our research. We want to make space for these uncomfortable situations where people can come to their own conclusions, without us necessarily naming what’s going on or what the problem of the image is; by creating room to sit with these uncomfortable truths.

IF: We are rather looking for ways of learning to listen to languages that are unfamiliar and learning to understand contexts that are problematic. Only then, can we translate and create visual work.

+++

Saskia Van der Gucht (BE)

is a visual artist and lecturer at Sint Lucas Antwerp. She obtained an MA in visual arts: jewellery l goldsmithing at Sint Lucas Antwerp in 2014.

saskia.vandergucht@kdg.be

www.saskiavandergucht.be

Irma Földényi (HU)

works in design, research and education. In addition to running her design practice STUDIO IF in Rotterdam, she teaches at the Willem De Kooning and the Gerrit Rietveld Academy. Irma has an MA from Design Academy Eindhoven in Social Design (2012, cum laude) and from the Moholy-Nagy University of Arts and Design in Product Design (2009). Before that, she studied as a goldsmith in Budapest.

irma.foldenyi@kdg.be

studio-if.nl

www.jewellery-perspectives.com

Since 2020 they work together as researchers at Precious Dialogue, a research platform for jewellery and treasured objects at Sint Lucas Antwerp.

Noten

- Mcclure, Tess. “Dark crystals: the brutal reality behind a booming wellness craze.” The Guardian, 17 Sep. 2019, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/sep/17/healing-crystals-wellness-mining-madagascar. Accessed 12 April 2021. ↩

- “Small-scale Gold Mining: Chinese Operations in Cameroon.” YouTube, uploaded by AFRASO, 19 Oct. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YFHn8Nutzw. Accessed 10 May 2021. ↩

- Ingold, Tim. “Surface Visions.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 34, no. 7–8, Dec. 2017, pp. 99–108, doi:10.1177/ 0263276417730601. Accessed 12 April 2021. ↩

- “Jim Paterson on the potential at the Pedra Branca project.” YouTube, uploaded by ValOre Metals Corp., 19 May 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JvFdL-mqp_w. Accessed 10 May 2021. ↩

- Carrington, Damian. “$10bn of precious metals dumped each year in electronic waste, says UN.” The Guardian, 2 July 2020, www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jul/02/10bn-precious-metals-dumped-each-year-electronic-waste-un-toxic-e-waste-polluting. Accessed 8 March 2021. ↩