Dit artikel verscheen in FORUM+ vol. 27 nr. 3, pp. 29-37

Het ‘ik’ onder de loep. Verborgen verhalen ontdekken via autobiografie

Manju Sharma

In this essay, visual artist and writer Manju Sharma reflects on the use of autobiography as a methodology for storytelling in the visual arts. She focuses on the methods that she uses to explore the self and its relatedness to the world that she wishes to grasp. She also sheds light on how autobiography fits into her artistic practice as a means of finding hidden narratives and to keep the personal narrative related to the world. The essay touches upon the use of personal stories, cross-linking and note-taking to unpack everyday sensitive issues that can allow people to find their voice and to speak out.

In dit essay buigt beeldend kunstenaar en schrijfster Manju Sharma zich over het gebruik van autobiografie als een methodologie om in de beeldende kunsten aan storytelling te doen. Ze focust op de methodes die ze aanwendt om het ‘ik’ te verkennen en vat te krijgen op de manier waarop dat ‘ik’ zich verhoudt tot de wereld. Bovendien verduidelijkt ze hoe autobiografie binnen haar artistieke praktijk past als een middel om verborgen verhalen te vinden en om het persoonlijke narratief te verbinden met de wereld. Het essay gaat in op het gebruik van persoonlijke verhalen, kruiskoppelingen en ‘het nota nemen van’ om alledaagse gevoeligheden onder de loep te leggen en anderen zo te helpen hun stem te vinden en het woord te nemen.

Chasing the soul

Dear lifeline,

Dear colonial entanglement,

Dear unintentional togetherness and relatedness,

Dear future,

Fragmentary notes. Either happy or terribly sad. This leaves

us chasing, always chasing.Autobiography as a methodology

Autobiography as a methodology in the visual arts can be understood as using a personal story from the self to create works of art. It is the use of personal life experiences to convey a story or narrative in visual form.1 Autobiography in the visual arts can also be used as a methodology for investigation into the everyday world to expose hidden narratives of marginalized individuals and communities. By hidden I mean they can reflect stories which are not covered in school curriculums and official stories of governments, or by journalists, as well as histories that require revisiting. It is a methodology that allows marginalized individuals or communities to find their voice and share their voice, and hopefully, to contribute to society at large.

Notation made with a photo camera to help record feelings. Pink Flower, 2015, Bratislava. Courtesy of the artist.

The autobiographical approach presents a methodology in which the position as a researcher and the researched are merged. The artist’s biography and its relatedness to the world becomes the research subject that is to be investigated through the making of artworks. The artworks become a place where personal and emotional debates have the potential to unfold in relation to larger social questions. This means that as an insider of your own research, you have private information that is unavailable to others until you share it.

Methods in my art practice, why I use them, why I like them

My investigational art practice is one in which personal storytelling provides a tool to unpack hidden voices and narratives. It is driven by a curiosity about why certain things are the way they are and why other things are invisible or unnoticed. These curiosities come from daily life experiences. The curiosity lingers for some time until I am ready to start unpacking it. The curiosity becomes a question which does not have an answer but provides an exploratory direction for my investigation. This means that I am not looking for an answer but instead try to unpack this curiosity-as-a-question layer by layer. This unpacking is not done in a systematic way but follows a rather chaotic and intuitive thread.

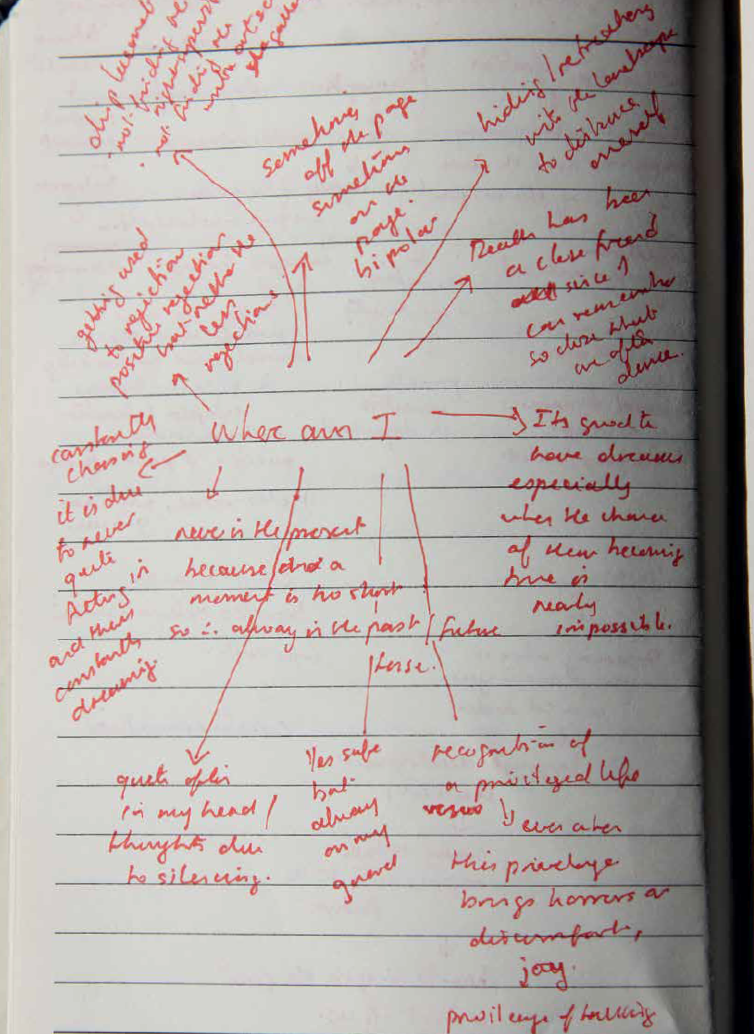

Photo of notations made in notebooks, a recording of thoughts, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Searching for hidden narratives requires recognizing forms of social relations that are otherwise unrepresented or misrepresented. It also requires the searching and understanding of one’s position, one’s privilege, and others’ positions and privileges. I also think it is important to search what has already been articulated on the subject matter of interest. For example, there are many definitions of nation and home. The definitions I use are influenced by the essay The Essence of a Nation by the French philosopher Ernest Renan2 in which he describes the deriving of a nation as an act of forgetting, and therefore also remembering. A second influential source is the book Race, Nation, Class, Ambiguous Identities by Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein in which they discuss how in defining a nation; race, gender, and class are inseparable.3 The questions that I pose for myself are: What is it that one wishes to remember? How reliable is that memory? What is it that one wishes to forget? How does the individual memory relate to the collective memory? How do race, gender, and class relate to the personal understanding of home and how can it define a nation? Furthermore, I am interested in the question of how to define a nation or a home through the modes in which we take care of others, ourselves, and each other.

As a black, Asian female growing up in England as of 1975, I was driven into silence. It is in this isolation that the space to think, to imagine, and to dream awoke. Through the arts, I have learned to find my voice and to use it in my art practice. Once the voice becomes emancipated, a privileged position arises in which one can demonstrate how the voice has been ignored. I therefore use what I call ‘a curiosity method’ – from asking questions and chasing possible answers – to addressing the absence of migrant voices in Western society. This method allows for meandering, unexpected encounters and keeping an open position. I identify with Michael Biggs and Daniela Büchler when they suggest, ‘In art practice, an answer is often less important than its pursuit’.4 It can therefore be seen as a part of a journey of which you don not know where it will lead you, and the urge to follow your curiosity is great enough to take the time and to make the effort.

Cross-linking is a method of forming bonds, for example bonds between places, objects, people, historical events, time, music, and texts. In forming these bonds, I particularly enjoy the freedom in which I can tell my own version of events, in the pursuit for possible answers. It is an ephemeral place and/or an in-between space which enables me to look from different perspectives and where confrontations can become uncomfortable before becoming comfortable. It is a place where I can harmonize my world in chord and discord. Through cross-linking, I am not looking for a completed jigsaw puzzle where all the pieces fit neatly together and make an all too coherent picture. I prefer the moment when the jigsaw puzzle is poured out onto a surface and when it is unclear if all the pieces are present.

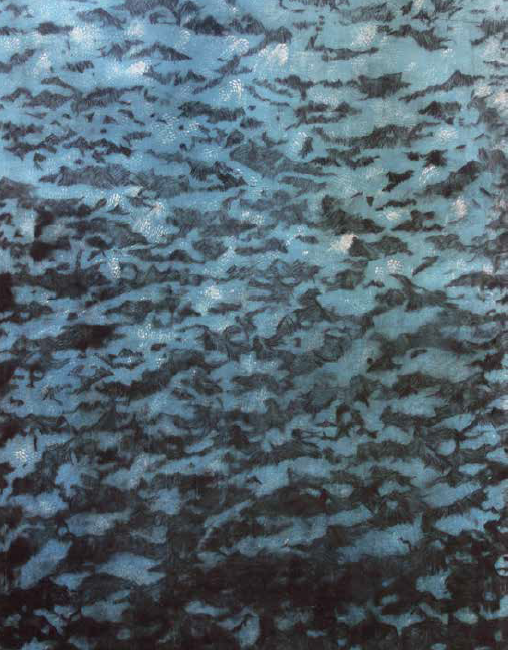

Notes using paint on family photos and the family album. Out of the Plastic 5, oil paint on canvas, 40cm x 30cm, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

By zooming in and out on different forms of relationships, such as with objects, events, and escape routes, this can help to enrich the dialogues. For me this implies looking inwards and outwards and concentrating on both the micro and the macro. It is an intimate acquaintance mixed with the complexity of the world in which we live. These discussions help project the personal accounts (the micro) onto a larger narrative in society (the macro). It is important to remain vulnerable within this complex environment of relationships, as I believe that this is where hidden narratives come forth.

By concentrating on primary emotions, such as hurt and shame, as a method of discovery, it has the benefits of possible healing. I am not an expert on healing but I do find that with the real intention of trying to understand how and why things are the way they are, that a space can open up for painful moments and allow healing to begin. It is a place where you can reflect on how you see yourself and how you see others, but also how others see you. It is a place where anger (second emotion) can become diffused.

Note-taking is a method to get the thoughts out of my head. Note-taking involves writing, filming, photographing, painting, and drawing. Note-taking explores my own thoughts and shared thoughts, be it from existing theory or from discussions with peers or family and friends, and from participating in workshops. These notes weave into images and paragraphs, developing a composition of voices to try and create a deeper level of exchange; a conversation with my world. The advantage of using various materials for taking notes is that you can experiment with which materials are best suited to express the narrative in the seminal work.

Curiosity: Brexit and how to say goodbye

In 2018 and 2019, my urgent issue was how to say goodbye to Britain. Brexit for me was not about whether England should be a part of the European Union, but related to the control of people. Therefore, my curiosity was searching for a way to say goodbye to what it means for Britain to be defined by its choice of borders, seeing people as quotas and monetary values, as the UK will implement an immigration policy established on a points-based system. The wish to say goodbye became my way of unpacking this moment or event, in other words, of concentrating on why and how to say goodbye. There are so many ways to say goodbye – or do I mean farewell? Resources that I have access to were used to start the investigation on how to say goodbye. Such resources include the internet, books, texts, sounds, discussions with colleagues, friends and family, documentaries, other artworks and artists, and the making of notes. From these resources, I really try to understand and ponder on my urgent issue. I also visited the area where I grew up, and made connections with history, objects, current events, music, and sounds that I found encouraging.

Notes using film that I used for the poetic film-essay Here and There, 2019, a still from film essay, HD video, duration 13’00”. Courtesy of the artist.

I began saying goodbye by writing a letter to a boy who used to live down the road where I was brought up. The letter contained a conversation that was both real and imaginary. We had a special relationship as he despised me for being a foreigner and I despised him for hating foreigners. In this discourse, I tried to use the emotions of hurt, shame, and abandonment we both experienced to discuss how our past has led to the current-day situation of Brexit. Parts of the text were adapted and used in my work (poetic film essay) called Here and There as spoken texts. The images for the film were made with my mobile phone and small camera that I normally carry with me. These cameras help to focus on the everydayness and to express the performative side of holding these cameras and using the body so the camera moves when we move. It was the way I wanted to explore the potential of the ordinary. The letter and the performative side of the film encourage the value of humans and in particular migrants, as I feel people have more to offer to a nation than just economic value.

The process involved thinking alone but also with peers, friends, and family, trying, making, failing, choosing, redoing, and negotiating. This includes the understanding of difficult texts, not being able to find the right words and experimenting with image-making because I did not know what the outcome would look like until a later stage. In this struggle of trying to mould the research and form, there is hope of a lucky strike. An important part of this practice is to make as many mistakes as possible, especially if you are working with sensitive topics, such as supremacies. With sensitive topics, you do not want to give any damaging signals that can hurt those who you wish to protect and therefore you must consider your ethical conduct. For example, in my case, the work should not invoke more prejudices, hatred, or new boxes of identities. Therefore, this process also enhances failure so that you remain sensitive to how your work can be received.

By sharing work, the practice gains relatedness in the social world. I like the term ‘creative interrogations’ used by art critic Irit Rogoff,5 as it also includes how the research should be viewed. Preferably, through engaging without drawing conclusions, and therefore leaving an open ending to allow further discussions and narratives to arise. Unlike more traditional forms of academic research, I do not have anything to prove, and as an artist I believe that we need to think about our areas of interest through care and form. So far, most of my work has resulted in discussion and feedback with peers. There is room for engaging in different spaces, and finding places where the results feed back into the process. In the future, I would like to help other people find their voice, which I can imagine taking place in learning and community centres. Therefore, to use autobiography as an encouragement of enrichment as it transforms one’s vulnerabilities into an environment of exploring. There is also a desire to ‘hang out’ more with my materials, allowing the various materials to develop a stronger visual language. A studio would be nice, but is not affordable, and therefore I constantly adjust to what is available.

Notes using drawing on how liquid borders and horizons are. Fluid routes, ink printed on paper, 50cm x 35cm, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

The methods described above are a means of finding hidden narratives and how to keep the personal narrative related to the world. For me, it is not about finding yourself, but a part of oneself, or a part of something/someone else, as the self does not exist in isolation but only in its relatedness to the world.

Conclusion

Autobiographical approaches in the visual arts can be an instrument for finding hidden narratives. I would wish the autobiographical forms of art to be useful, as they address the absence of diverse voices in our society and in the field of art. They also may address the question of what type of knowledge is useful, to whom, and when? I hope as others have spoken before me and encouraged me to do the same, to encourage more people to find their voice and to speak out, as slowly but surely, we leave traces of our realities. This methodology provides not only the liberating experience that one finds unexpectedly reflected in one’s own personal story, but also to enrich society with a variety of realities. The more diverse worlds we discover, the richer the knowledge. Marginalized bodies are still too often unrepresented and misrecognized and it is in our vulnerabilities that we have strength. The artworks that roll out from this methodology hopefully not only speak of the self but also for those who can relate to them. An important question embedded in this methodology is for whom the artist can speak and for whom the artist cannot speak. I find this question difficult to answer, but I do hope that my work, through its relatedness with the world, resonates with other similar bodies. For those who cannot relate to it, I hope they understand a little more of how different realities exist in close proximity.

+++

Manju Sharma

is a visual artist and writer. She was brought up in the UK, and now lives and works in Zeist, the Netherlands. Sharma recently graduated with a Master in Fine Arts from the HKU (2019), Utrecht. She held a Post Doctorate position in Accountancy (obtained in 2003) and Bachelor in Fine Arts (2017) from HKU, Utrecht. In her art practice, Sharma examines the concepts of heritage, foreignness, and identity. Through the personal, and the everyday, she unfolds narratives embedded in social and political landscapes.

Noten

- Examples of artworks that have been produced in the past using autobiography as a method are the following: Tulsa (1971), by Larry Clark, I am too sad to tell you (1971) by Bas Jan Ader, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With (1995) by Tracey Emin, Roadworks (1985) by Mona Hatoum. More current-day artists include works Bridgit (2016) by Charlotte Prodger, Out of Blue (2002) by Zarina Bhimji, and The Devotional Wallpaper (2008 onwards) by Sonia Boyce. These works are not claimed to be autobiographical by the artists, but are works that I feel contain strong elements of autobiography as a method. ↩

- Essay: Renan, Ernest. What is a Nation? ‘The essence of a nation is that all individuals have many things in common, and also that they have forgotten many things.’ The original texts are from a lecture in 1882. The essay is translated and annotated by Martin Thom. The essay forms part of the book Nation and Narration, edited by Homi Bhabha, Routledge 1990, p. 11. ↩

- Balibar, Etienne and Wallerstein, Immanuel. Race, Nation, Class, Ambiguous Identities. Part I and Part II. Translation by Chris Turner, New York, Verso, 1991 (first published in 1988). Both Balibar and Wallerstein recognize that nation states are constructed with racism and it is necessary to understand its relation to class and capitalism. ↩

- Vytautas, Michelkevicius. Mapping Artistic Research, Towards Diagrammatic Knowing. Biggs, M. and Buchler, D., Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, 2018, p. 113. ↩

- Online video: Rogoff, Irit. Becoming Research, MIT 2018. Vimeo, uploaded by ACTMIT, 9 April 2018, vimeo.com/271887079. ↩